**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

Temporary Noon (1995-1999)

Despite all the positive attention he received after Permanent Midnight’s success, things didn’t instantly completely turn around for Jerry Stahl. His longstanding dream had finally come true with his first book publication, but he had to face a (no pun intended) sobering dose of reality that the vast majority of all writers, published or unpublished, eventually have to face: he still had to make a living. On top of his efforts to keep his sobriety, Stahl also had to hustle and struggle for some time after Midnight’s publication to stay afloat.

Stahl continued to write articles for numerous publications during and well after this time. Right after Midnight’s publication, for instance, he covered a Republican convention for Esquire UK. He also did some ghostwriting under the pseudonym of Betsy Dexter, penning a series of books that were released in 1995 and titled You Must Remember This, which contain random facts revolving around a given year. He even had to take work outside of writing and, at one point, had a job moving furniture. Stahl had no choice but to live modestly during this time, staying in places like a Silver Lake studio apartment and the Hollywood YMCA.

Also around this time, Stahl was given an advance by Warner Bros. to write a sequel to Permanent Midnight. Titled If You Die Now, We Can Make You Famous, Stahl quickly lost interest in the follow-up memoir and never finished it. He didn’t like not having drugs as an excuse for his behavior, anymore, and he also had reservations about his daughter (who he was then seeing as often as he could) reading it someday. Despite needing the money, Stahl returned the advance in full.

Many producers expressed interest in adapting Permanent Midnight into a feature film in the years following its release. Nothing actually came through, however, until Nancy Ferguson, wife of Devo lead singer and Stahl’s friend Mark Mothersbaugh, introduced him to producers Jane Hamsher and Don Murphy.

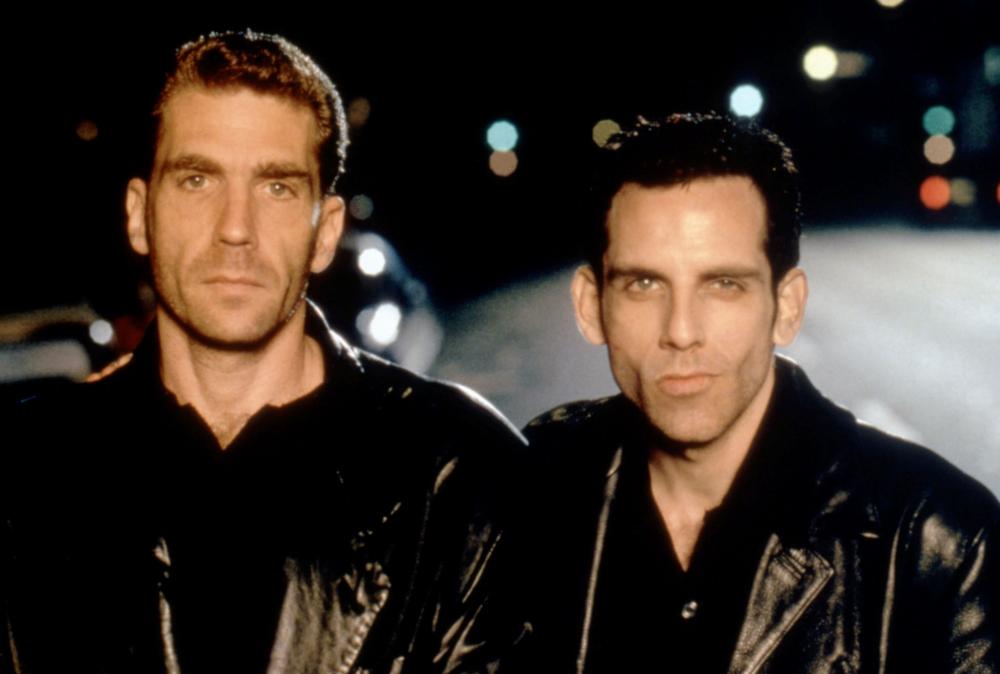

Then best known for their work on Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, the then-hot pair had the interest and track record to make the film a reality. Hamsher and Murphy’s former USC classmate and NBK co-screenwriter David Veloz was hired to adapt the screenplay and make his directorial debut with the film. Jon Bon Jovi and David Duchovny were, at one point, set to star as Stahl, but their commitments both fell through. Then-rising talent Ben Stiller wound up committing to the role, something that would go on to have a monumentally positive impact on Stahl’s life.

Financing for Permanent Midnight’s feature film adaptation took nine months to come together. Stiller, who was fully committed to the project, turned down other acting roles so he could keep his schedule open for the film. Stiller and Stahl had been discussing the role, and their talks evolved into a close personal and professional relationship. They hit it off so well that Stiller suggested they try their hand at writing a script together while waiting for the Permanent Midnight money to come through. Stiller had the perfect project in mind: a big-screen adaptation of Budd Schulberg’s classic old Hollywood novel, What Makes Sammy Run? Stiller later said, “Why did I ask Jerry? I knew he was a good writer and I was scared out of my mind to do it alone.”1

Though the film has yet to be produced, the Sammy adaptation is a passion project that Stiller pursued for many years. The project started at Warner Bros., then went to Fox, then was eventually sold to Dreamworks, where Steven Spielberg reportedly deemed it as being anti-Hollywood and went so far as to say it should never be made. The project is still somewhat legendary, however, with Stahl observing, “There are good projects that don’t get made all the time. Most aren’t famous for not getting made.”1

Stiller proved to be Stahl’s most noteworthy creative partner since Stephen Sayadian. Stahl learned a great deal from working with Stiller, who, despite being over ten years his junior, served as something of a mentor to the former’s re-entry into screenwriting. Stahl realized he was working with someone that he considered to be a genius when Stiller figured out a way to condense a large amount of information and a long passage of time in the Sammy book by making it appear as a montage imagined on a movie screen by the lead character.

Stahl and Stiller also wrote a remake of the 1942 comedy, The Magnificent Dope, around this time. The story revolves around a contest to find the biggest failure in the United States. Like Sammy, the project has yet to reach screens.

Stiller and Stahl went on to collaborate on many projects over the years, both produced and unproduced. Their friendship also flourished, as evidenced by Stahl’s co-dedication of his first-published novel to Stiller and by Stiller’s decision to make Stahl the best man at his May 2000 wedding. Stiller even went so far as to buy Stahl a tux and personally fly him to Hawaii to assure that his close friend and colleague could attend the ceremony.

Before the wedding and other events took place, however, Permanent Midnight still had to be made and released. When financing eventually came through, the film went into production with Stiller, Elizabeth Hurley, Maria Bello, Owen Wilson, Fred Willard, and Janeane Garafolo in lead and supporting roles. Stahl was often onset, serving as both a history consultant and as Stiller’s instructor on how to properly shoot up heroin. Stahl was even an actor in the film, playing the small role of a methadone clinic doctor who cynically tells Stiller he won’t get clean.

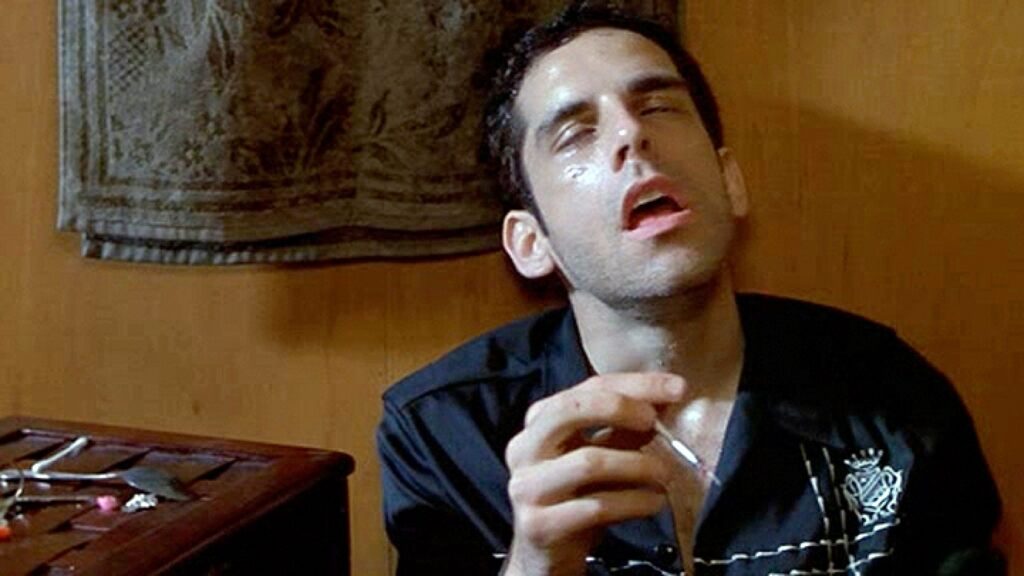

Personal stories that Stahl told to the cast and crew, some of which didn’t find their way into his book, would sometimes make their way into the movie. The highly cinematic scene where Stiller smokes crack and repeatedly throws himself against a high-rise window with his drug dealer, for instance, was first relayed to Veloz as an anecdote from Stahl’s days working at Hustler.

Though he admired his talent, Stahl had some concerns about Veloz’s early drafts of the screenplay and his lack of understanding about hard drugs. Veloz himself stated at the time of the film’s release, “I think he had his reservations… I can’t imagine doing what Jerry did, writing a book about my life and then handing it over to somebody else.”2 Co-producer Jane Hamsher had previously described Veloz as a “stable, reliable churchgoing Mormon,”3 so he probably wasn’t the best fit for telling Stahl’s drug-fueled story.

After the first cut was assembled, Stahl and Stiller were unhappy with the film, which resulted in the addition or reshooting of select scenes. Voice-over narration was also added to the final cut.

Permanent Midnight had its theatrical release in September 1998. It didn’t make a huge splash with audiences or critics. Roger Ebert, however, gave it a positive, three-out-of-four-star review, remarking on the “savage impatience”4 of Stiller’s performance. Ebert offered his own take on the film’s depiction of addiction, remarking, “Stahl doesn’t seek drugs because he wants to feel good but because he wants to stop feeling bad. It isn’t the high that makes people into addicts; it’s the withdrawal.”4

The film still managed to have enough of an impact to forever change Stahl’s reputation. One of the most memorable and darkly hilarious scenes in the movie comes directly from the book. It involves Stiller shooting up in a public bathroom while hallucinating an angry and disapproving puppet for whose show he is writing. Though the puppet in the movie was given the name of Mr. Chompers instead of ALF (presumably for legal purposes), enough people still made the connection. ALF, from then on, would be publicly linked to Stahl’s name in the mainstream.

The film Permanent Midnight functionally tells Stahl’s story, contains a powerhouse performance by Stiller, and is an overall success as an addiction survival film. However, it doesn’t fully capture the book’s heart and humor or, most importantly, Stahl’s voice.

In the book, Stahl tells his stories, even the worst of them, with a dryly humorous and, oftentimes, absurd tone that is balanced by moments of stunning honesty and sensitivity. The movie relays the events of Stahl’s life in a very uninspired, emotionless, and movie-of-the-week fashion. Though it’s solid and well-made on a technical level, it just doesn’t know how to fully capture what makes the book so monumentally special. As Maria Bello tells Stiller after reading one of his articles in the film, “It sounded like you. Proved you were real.”5 If only the movie itself had listened to and implemented this astute observation…

Working on the movie and seeing the finished product, however imperfect it may be, deeply impacted Stahl. He stated, “seeing the worst moments of your life projected nine feet high by people that vaguely resemble you—it’s like years of therapy in 90 minutes.”6 Though it was painful for him to see, he still found much to love in Stiller’s performance, stating, “The movie is an existential nightmare on some levels… But the upside is, Ben got it. If somebody played me and just did the khaki version, it could’ve been grim.”2

For a variety of reasons, the film adaptation of Permanent Midnight had many positive effects on Jerry Stahl’s career. Aside from it introducing him to Stiller, it also brought him attention (some of which he didn’t want) and made a significant amount of people more aware of and interested in his work. After the film’s release, Stahl started to get regular screenwriting work again, primarily, at first, with ghostwriting and uncredited script doctoring.

Fully sober and, once again, employed, he wrote as furiously as he ever had. At one point during this period, Stahl wrote an animated pilot for MTV with Mark Mothersbaugh, but it never found its way to production because it, in Stahl’s words, “turned out to be so disturbo and surreal they got weirded out and passed.”7

Most important for Stahl at this time was the work he was doing on what would become his first-published fiction novel. Stahl described the book by saying, “It’s about a fifteen-year-old in 1970 who can’t make it as a hippie because he doesn’t do well with groups… It’s like a prequel to Permanent Midnight in a way, but much, much darker.”2 Stahl stated that the book took him a couple of years to write “mostly because I had to keep stopping to try and pay the rent.”7 Perv–A Love Story was eventually published in September of 1999.

Perv fearlessly exhibits all the primary and essential qualities that define Jerry Stahl’s best and most personal works. It has an overall darkly humorous tone while still containing moments and observations that are painfully and movingly truthful. It has an obvious affection for and fascination with damaged people and relationships that are built on mutual pain (a topic even more closely examined in his next book, Plainclothes Naked). There are also plenty of moments containing extraordinarily perverse (and increasingly brutal) sexuality along with select instances of graphic, wince-inducing violence. It should go without saying that the book also depicts more than its fair share of heavy drug use.

It’s hard to define Perv as any one thing because it both belongs to and simultaneously defies a multitude of genres. The same can be said for all of Stahl’s fiction, but Perv is the first and, quite possibly, strongest example.

Before examining Stahl’s fiction, it should be noted, as previously stated, that he claims to write with emotion and instinct over intellect. With fiction, he doesn’t have to concern himself with the consequences of writing about and/or naming real people. He can freely and nakedly write exactly whatever it is that he’s feeling. Stahl provided insight into his process and the nature of his work when he stated, “It’s not like you really have a choice about what comes out when you sit down to write. Subjects choose you. Emotions choose you. Scenarios choose you. For whatever reason, whether it’s the life I’ve led or a batch of bastard neurons misfiring in my brainpan, so-called over-the-top stories and situations don’t seem that over-the-top to me. You see enough extreme-o, eventually it doesn’t seem so extreme.”8

With the experience of writing Permanent Midnight still fresh on his mind, combined with the emotional rawness that his ongoing sobriety brought on, Stahl was, no doubt, looking back on the origins of his life and his pain while writing Perv. That started with his family, his upbringing, and his youth. What came out may have been out of his conscious control, but it wound up being, at that point in time, the most emotionally honest piece of writing he’d ever published. With Perv, Stahl could finally say all the things he so desperately needed to say and still maintain some semblance of privacy. He could return to the emotional hell of his past and, through the buffer of fiction, discover truths about himself and his loved ones that he never could while strictly writing about reality.

Reading the book gives the impression that it served as an exorcism to its author’s past pain. This relief, however, would never be entirely complete or permanent, as many variations of the themes and characters in Perv would still find their way into future novels and memoirs. Stahl once explained, “Hubert Selby [had] this great saying that ‘the bottom is bottomless’, which is to say that you can exorcise 15 demons only to discover that the 16th is the motherfucker that’s gonna kill you.”10

Perv is first-person narrated by Bobby Stark, a fifteen-year-old who is thrown out of his private school after getting snitched out for losing his virginity in a group sex act with some of his classmates and a local girl. Before he is tattled on, Bobby is first caught by the girl’s one-armed barber and tattoo artist father. Bobby is forced to listen to the man’s almost comically painful problems as he relays stories of his troublesome daughter and his acromegaly-suffering wife. Bobby is also treated to/forced to accept a present from the father in the form of a rose-shaped tattoo over his heart so that he will always remember the special occasion.

While driving home with his mother from the airport early in the book, Bobby spots “a trio of saffron-robed Hare Krishnas doing a twirly dance to the accompaniment of clapping, tambourine, and an unpleasant-sounding Hindi chant.”9 Bobby then states that he recognizes one of them as “Michelle Burnelka. She’d been in my class from kindergarten until the tenth grade, my last year in public school before I got sent away. And I’d pretty much loved her the whole time.”9 Bobby goes on to bluntly explain, “The first time I masturbated, I was daydreaming about saving Michelle from a fire.”9

Once home in Pittsburgh, Bobby is lonely and depressed, forced to live with his mentally ill and “well meaning but badly electroshocked mother.”9 Out of loneliness, he searches for Michelle’s family in the phone book and, by chance, happens to reach her on the telephone. Michelle remembers Bobby from grade school and they meet up at a shopping mall parking lot. Michelle, it turns out, is now “hardened” and had run away and joined the Krishnas to get away from her stepfather and his “hands like helicopters.”9 Bobby observes, “What her stepdad had done, as far as I could figure, took up all the space in her brain.”9 Michelle later confides in Bobby, “first grade was the best year of my life. After first grade, everything that happened was the opposite of what I wanted.”9

Michelle has also run away from the Krishnas and is looking to start over. An impromptu road trip ensues when the two teenagers decide to hitchhike across the country to San Francisco. At first, Bobby and Michelle’s trip is uneventful. Bobby endlessly lusts after/is infatuated with the severely damaged Michelle, who, aware of herself beyond her years, occasionally toys with his desires. Bobby at one point observes, “All that hardness left her when she giggled, and I realized why I loved her all over again. There was a funny little girl inside the tough-as-nails chick she tried to foist on the world. I felt almost privileged she let me see it. I felt like she let me in.”9 Bobby is equally mesmerized and intimidated by the street-smart girl, at one point wondering, “How was it possible to be so turned on and freaked out in the same breath?”9

Eventually, Bobby and Michelle hitch a ride with two hippie-looking young men who are heading to Hollywood and go by the names of Meat and Varnish. Things get steadily worse as the encounter draws out for nearly seventy pages, culminating in a shocking (yet strangely and darkly hilarious) climax that depicts “Weirdness on top of weirdness”9 and pushes just about every boundary imaginable as far as sex and violence are concerned.

Without providing too many spoilers, the book ends with an epilogue set in the future at the then-present time of Perv’s initial publication. Saying too much would ruin a beautifully surprising ending, but it can be said that Perv’s final moments solidify Stahl’s extraordinary gift for invisibly shifting tones in his writing. Despite the graphic and raw nature of most of the book, it dares to end on the most shocking note of all: somewhat saddened, sincerely optimistic, and entirely earned sweetness.

Countless parallels between Bobby and Stahl can be found within Perv. Through dramatized fiction, Stahl is able to fully convey just how absurd, painful, uncomfortable, and traumatizing his past was when he experienced it. The book makes the reader understand what it truly felt like to be Jerry Stahl during his youth.

For instance, Bobby’s father committed suicide not long before the story begins, with Bobby being the same age as Stahl when he lost his father. Bobby’s father stepped in front of a street car, however, a much more violent and brutal method than the carbon monoxide poisoning described in Permanent Midnight. The choice allows the reader to understand the loss on a deeper and more visceral level.

The mother character in Perv also parallels Stahl’s mother as she was described in Permanent Midnight. The relationship between Bobby and his mother offers an uncompromised depiction of the anger, hurt, and shame that are associated with being raised by someone so irreparably broken. Stahl allows Bobby to think, relay, and, sometimes, enact a number of otherwise unmentionable thoughts regarding her.

“From diapers on, I felt like there was something not good about me, but it was invisible to everyone but my mother,”9 Bobby states early on. He also remembers a story about his father’s funeral where, in response to his mother making a scene, he remembers harshly whispering to her, “I hope you die. I hope that more than anything.”9

Just as important as what is presently happening to Bobby externally is his interior life, which takes up a good portion of the book’s nearly 350-page length. Throughout the book, we experience all his random thoughts and his ruminations on past experiences that brought him his pain and made him such an outsider in the first place. In a particular sex-and-drug-fueled moment, for instance, Bobby goes deep into thought about a childhood memory where his father tenderly lectures him on the importance of powdering one’s balls in adulthood.

Through Bobby’s interior life, the reader experiences many complex feelings. Thoughts about and snippets of scenes from his father’s suicide are littered throughout the book, always haunting Bobby regardless of what’s happening directly in front of his eyes. “I felt closer to the guy since he’d been buried than I ever did when he was walking above ground” and “his dying gave me an excuse to feel the way I already felt”9 stand out amongst Bobby’s many aching admissions regarding the loss of his father. He later elaborates further, “I was ashamed because my life was so much easier than his, yet I was still unhappy… His death, finally, let me feel like his son.”9

Perv—A Love Story is heavily comprised of raw, alienated, and somber emotions that are communicated with an overall darkly absurd tone. It is articulate, intelligent, rambling, disgusting, endlessly perverse, and boldly sensitive all at once. It is one of the most honest and revealing books of its time, along with being one of the most unjustly under-known. It may very well be Stahl’s greatest and most personal accomplishment, but that’s hard to state definitively given the quality and nature of his other works.

Ben Stiller’s production company, Red Hour Productions, at one point owned an option on Perv. Showtime and New Line also considered making it into a series, but they both eventually passed. Future close friend and collaborator Philip Kaufman was also interested in directing a film adaptation of the book, but that also never came through.

A New Attitude (1999-2000)

Jerry Stahl found that his talents were in demand shortly following Perv—A Love Story’s publication. His screenwriting career, in particular, was starting to take off all over again. Around this time, he worked on “a crazy-ass tv pilot being produced in association with Oliver Stone”1 and “a totally unmakeable movie for 20th Century Fox.”1 Neither of these projects ever found their way into production.

Stahl also befriended Johnny Depp during this time, meeting him through a mutual friend, writer Nick Tosches. This led to Stahl being hired to write a cop thriller produced by Jerry Bruckheimer for Depp to star in, but this project never made it to production. Stahl also continued to take uncredited script doctoring jobs, most notably on the Ben Stiller-starring Meet the Parents, to which he added the concept of Stiller’s emasculated character being a male nurse.

Stahl’s attitude towards screenwriting evolved and hit a new level of maturation around this time. Before, his admitted snobbery and drug-influenced bad attitude made it seem like work that was beneath him. Upon his re-entry into the vocation, however, he had a different take: the end result of a screenwriting job has nothing to do with his artistic vision, it’s the producer and/or director’s vision that he’s being paid to help fulfill. The final product is ultimately their movie or television show.

At the end of the day, Stahl now had the life experience to know that screenwriting was not a job at which to scoff or about which to complain. He stated, “Anytime I hear a screenwriter bitch about the indignities of his or her profession, I want to tell them, ‘Go work at Mickey D’s for a few weeks, motherfucker. Then come back and talk to me about humiliation.’”1.1 Because Stahl is incapable of completely phoning anything in, however, he has also stated that he always has to face the challenge of finding at least one thing he can relate to in any writing job he accepts.

Stahl, with years of experience behind him, said about his newfound attitude: “I fell into a few gigs while in a state of not-too-elegant heroin addiction. I was always trying to be a novelist, and took TV gigs the way you’d temp at Macy’s at Christmas: because the opportunity came up, not because you envisioned a lifetime of Macy’s counter-work. Mind you, now I love writing for TV, when I have the opportunity, because you can do cool shit and some of the best writing in the world is out there. To me, at this point, it’s all writing—just different delivery systems… [T]he great thing about show business [is] collaboration… Novels, I’m not the first to notice, can be punishingly solitary. When you work for the screen—big or little—you have an excuse to hang out with some of the smartest, funniest maniacs on the planet.”2

Though he had a newfound interest in and gratitude for screenwriting work, Stahl’s primary passion was still for his personal works: the books and articles that were his and his alone. In early 2000, Stahl even tried his hand at a spoken word album that consisted of pieces of his writing. Titled So Ends My Hollywood Minute, the half-hour CD uses jazzily psychedelic and abstract sound designs and experimental sound editing and mixing techniques to highlight Stahl’s direct, matter-of-fact readings of his work.

“Maybe it’s not the city. Maybe it’s not the woman or the drugs,”3 Stahl repeatedly wonders/states in the CD’s opening track and later concludes, “maybe, call me a freak magnet, it’s just me.”4 The CD also contains a funny and moving story, a version of which was previously relayed in Perv, about Stahl bonding with his father as a child over the issue of powdering one’s balls as a man.

The CD also contains many frank observations and stories about heavy drug use. “The only difference between dope and alcohol,” Stahl observes, “is that the booze makes you look worse. The sauce turns you red and the needle turns you green. One turns you into a nightmare, one turns you into a nightmarish joke. Dope, at least, preserves you.”5

On the album, Stahl also examines life on both the inside and the outskirts of L.A., concluding with a track that sums up his then-feelings on the city: “Somehow, between hanging out at Madame D’s and writing smacked-out shotgun in my baby’s dominatrix mobile, I came to a strange conclusion regarding the burgh I inhabited. That there exists some slick, subterranean pool of self-loathing and toxic desire from which springs L.A.’s true inspiration. The truth, everything in this city exists as the opposite of its faux self so that, despite the hype and blather, it’s not about money, it’s not about fame, it’s not even about entertainment. Not even close. And this miniature domain of reality called Hollywood, it’s about the twisted redemption of hollow visionaries looking to inform their lives with the substance that their very creations, those simulations of life called tv and movies, lack entirely.”6

Stahl was married for a second time around this period, again to someone who worked behind the scenes in the entertainment industry. The marriage would not be a long-lasting one, however.

The Pain Snob continues in part 4 of 7.

< 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources >