**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

TV Junkie (1985-1992)

Many of the details of Jerry Stahl’s life during the time period that’s about to be explored, along with the years that have already been covered, have previously been thoroughly conveyed by Stahl, himself, in Permanent Midnight. For the purposes of this piece, we’ll go relatively light on his personal life from this point on so we can pay more attention to the work, itself. It should also be noted, however, that it is hard to pinpoint what, exactly, Stahl’s contributions were to the scripts he was credited for co-writing during this next time period of focus, as he claims that he was constantly fired and rewritten. Not to mention, his then-heavy drug use has since made it next to impossible for him to remember such details.

After his adventures in porn, Stahl found himself still working as a journalist. He semi-regularly wrote for/was published by Playboy from 1984-1992. While working for Playboy, he conducted interviews (his experience in interviewing Mickey Rourke in 1987 is hilariously detailed in Permanent Midnight), wrote essays (he recalled his Café Flesh experiences with a 1985 article, Café Flesh and Me: Confessions of a Cult King, which is quoted in this piece), and had short stories/chapters from early rejected books published (I’m Dick Felder! and Finnegan’s Waikiki were published by the magazine in the late ‘80s and later appeared in Stahl’s short story collection, Love Without).

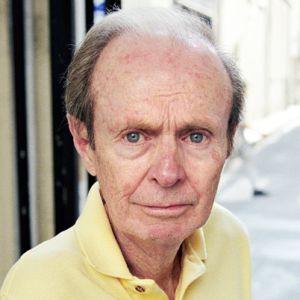

Though his drug use continued to increase, Stahl remained a productive professional for as long as he could. “He never missed a deadline,” said Stahl’s Playboy editor, Stephen Randall, “At some level, I always knew [he had a drug problem]. But I had no idea he was that tormented.”1

Stahl’s credit for co-writing Café Flesh wound up opening some doors for him in Hollywood. A script reader who was Stahl’s soon-to-be first wife saw the film and was impressed enough by its originality that she introduced him to Tom Patchett, an established television producer and writer who helped introduce Stahl to the industry by bringing him on board a show on which he was then working.

Stahl received his first network television writing credit for the NBC series, You Again?, which was created by Eric Chappell and centers on a conservative divorcee (Jack Klugman) whose teenage son (John Stamos) moves back home. Typical for Hollywood, Patchett was soon fired from the project and Stahl was left to deal with the brash and difficult Klugman on his own. Stahl was credited for writing two episodes of the short-lived series in 1986, titled Bad Apples (in which Klugman tries to enroll Stamos in a private school) and Enid Quits (in which Klugman’s longtime housekeeper quits).

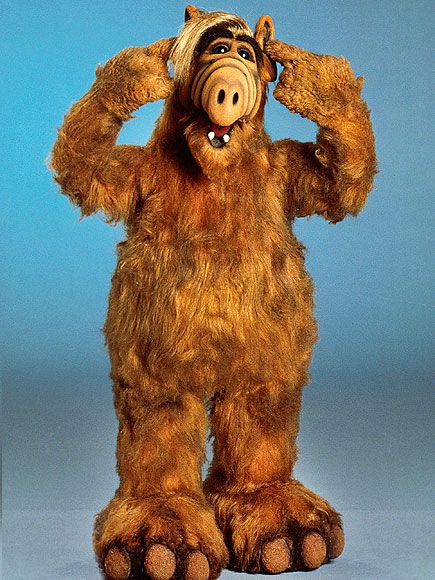

Stahl’s next television writing credit, also in 1986, would go on to haunt his professional life and public reputation in the years to come—so much so that people would often mistake him for the show’s creator. Co-created by Patchett along with Paul Fusco, ALF was a hit NBC series about a wise-cracking alien whose ship crashes into the home of an all-American family.

Stahl’s first ALF episode (which ran over a hundred pages in his first draft—roughly four times the length of a regular sitcom) was titled Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue? The unintentionally creepy episode centers on the presumably adult-aged ALF’s romantic infatuation with the household’s teenage girl, Lynn (Andrea Elson). The furry alien even goes so far as to ask her mother (Anne Schedeen) for advice on how to hook up with her underage daughter. Schedeen does, at least, express some reservations: “I don’t like the idea of ALF having a crush on our daughter, ”she says to her husband, “I’d like to be able to show people pictures of our grandchildren.”2 As was often the case with ‘80s entertainment, everything in the episode is delivered with a naïve and, on the surface, wholesome innocence that is seemingly unaware of how wholly inappropriate it actually is.

Stahl went on to be credited for co-writing two more episodes of ALF in the following years. Since neither of them carry the same amusingly hidden perversions, they are not as memorable or as noteworthy as his first. 1987’s La Cuckaracha sees ALF battling an oversized cockroach from his home planet. “You’re angry at the world, I can feel it,” ALF tries to sympathize with the creature, “You probably didn’t get enough love as a larva.”3

1989’s Mind Games is a comparatively dull episode that centers on ALF’s attempts at becoming the family’s in-house psychiatrist. It’s possible, upon close inspection, to find some potential insight into Stahl’s strong dislike of psychotherapy with such lines as, “Carl Jung was a big weenie head.”4

In the middle of his time writing for ALF, Stahl also contributed to Marshall Herskovitz and Edward Zwick’s ABC drama series about the travails of white middle-class Philadelphians, Thirtysomething. The show was about as far from Stahl’s artistic tastes as he could get. His first credit, 1988’s appropriately titled Born to Be Mild, centers on the horrifically vanilla dilemma of characters who have to choose between their weekend plans and babysitting. In 1989, Stahl was also credited for contributing to the story for an episode titled Politics, which centers on two characters who go to work for a potentially shady politician.

In 1989, Stahl was credited for co-writing two episodes of creator Glen Gordon Caron’s ABC comedic detective series, Moonlighting, starring Bruce Willis and Cybill Shepard. Plastic Fantastic Lovers centers on a mystery surrounding a character’s botched plastic surgery procedure, which makes him, in his words, a “prisoner in my own house. Reviled by family and friends, set apart from the rest of humanity.”5 Though it’s hard to be certain, the phrase “closet kinkoid” and thoughtfully observant lines such as “You men… You always want to put us on a pedestal or down in the gutter” and “Our culture treats aging as if it were some kind of illness”5 seem to come directly from Stahl’s hand.

Stahl’s next Moonlighting episode, Perfetc, centers on a dying criminal who involves Willis and Shepard in the story behind a twenty-five-year-old “perfect” crime. The episode examines fame and the desire to be remembered. “Making your mark, being immortalized” and the “real accomplishment”6 of celebrity are what the criminal is seeking above all else. Stahl would also serve as a story editor for seven other episodes of the series. Despite his lack of interest and his increasingly drug-addled state at the time, Stahl’s lively writing style was actually a good fit for Moonlighting and its reliance on snappy dialogue exchanges and clever wordplay.

Shortly before Perfetc aired, Stahl became a father for the first time when his then-wife delivered their daughter at the end of March 1989.

1989 was, needless to say, a busy and important year for Stahl. The third and, to date, final feature-film collaboration between Stahl and Stephen Sayadian was released late in the year. Since this production was R-rated, this was their first collaboration where they were credited with their real names. Though Dr. Caligari wouldn’t have quite the same impact as their early ‘80s surrealist hard-core efforts, Nightdreams and Café Flesh, the film still managed to make its mark with cult audiences and wound up being a low-budget success.

The project came about after Sayadian collaborated on a dream sequence for director George A. Romero’s 1988 horror film, Monkey Shines. A producer saw his work, liked it, and offered Sayadian $200,000 to make a Dr. Caligari movie. Though Sayadian initially wasn’t interested, he eventually thought of a way to make it work and agreed to do it.

In Sayadian’s updated interpretation, Dr. Caligari (a commanding Madeleine Reynal) is now the granddaughter of the original titular character from the 1920 classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Like her grandfather before her, Sayadian’s Dr. Caligari is brilliantly mad and also performs outrageous experiments on her patients. “There is only one reality,” she proclaims, “and I write the laws.”7

The primary focus of the film centers on Caligari’s mind-swapping of a cannibalistic serial killer (John Durbin) and a nymphomaniac housewife (Laura Albert). To what end isn’t entirely clear, but bothering with such logic only misses the point. Dr. Caligari (originally released as Dr. Caligari 3000 in theaters but later shortened for video) is as challenging and nightmarishly abstract as Stahl and Sayadian’s previous collaborations. It doesn’t go quite as far in its depictions of graphic and perverse sexuality, but the film is still as bold and unsettling as the previous works. Though slightly more narrative-driven this time around, Dr. Caligari is still sometimes difficult to follow. If you surrender to its fragmented dream logic without trying to make too much sense out of it, however, it’s a highly rewarding film on a daringly experimental level.

Like Sayadian’s other films, the ‘storyline’ isn’t nearly as important as the film’s mood, atmosphere, visual aesthetics, and overall tone. Dr. Caligari is set within a world of colorfully expressionistic—though equally minimalistic—sets and costumes that make it resemble an adult-oriented episode of Pee Wee’s Playhouse or an ‘80s rock video on a bad acid trip. There’s a colorfully low-budget Tim Burton/Federico Fellini feeling to the film that is often offset when the dream-like visuals become absurdly stomach-churning.

The film’s many bizarre, surreal, and/or sexually disturbing moments involve such things as transitions that feel like they were taken directly from Eraserhead, a grown man in a baby mask having sexual intercourse with Albert’s insatiable housewife after deeply cutting her wrist with a straight razor, a woman proudly showing off absurdly enlarged breasts that are longer than her arms, Durbin’s deranged cannibal getting off on an Electro Convulsion Therapy session, Albert encountering a grotesquely large and fleshy entity with protruding and sexualized tongues sliding their way out of oozing orifices, the inexplicable scalding of Albert while she performs a hand job on a lifelike scarecrow, the slicing of a blood-and-organ-filled birthday cake, Albert anally penetrating a screaming man with an elongated growth on her arm, and, last but not least, the mind swapping operation performed by Dr. Caligari by way of large needles being stuck into her patients’ restrained foreheads.

Sayadian credits Stahl for writing a long monologue in which Durbin’s cannibal goes into a disturbingly detailed account of his experience in turning a woman into stew: “Her face kind of floated on top of the stew, you know, kind of like a lotus blossom. I seen one on a calendar once. Her face just floated… lookin’ up at me with them maraschino cherry eyes. You don’t think I’d boil her peepers, do you? Kind doctor, sauteed is the only way to serve an eyeball.”7

Sayadian also credits Stahl for writing what he refers to as “dreamland”8 dialogue. “[Stahl] was really great at writing dream language,”8 Sayadian has said, though he also admitted that this probably had as much to do with Stahl’s drug use at the time as it did his talent. Dreamy and surreal dialogue like the following passage delivered by Durbin after the brain swap is indicative of the consistent unreality and disconnected haze that occurs during a life dependent on heavy drug use: “I see my face and I think, ‘Who is that stranger? Whose eyes are these? Are these hands connected to him?’ And the worst part, the worst part…? Where’s the rest of me?”7

Though Dr. Caligari never found more than a small cult audience, Sayadian knew from past experiences how to turn a profit with a smaller film. He went to Toronto to sell the film in different markets and managed to collect $750,000 in deals, almost four times the original budget of the independently-produced film.

Stahl’s next television credit was in June of 1990 for a co-story (along with teleplay writer Karen Hall) contribution to a quirky, Twin Peaks-esque series set in a small Alaskan town called Northern Exposure. Stahl’s credited episode centers on lead Rob Morrow’s doctor character inheriting a 140-acre forest estate from one of his deceased patients. The charming episode, titled Soapy Sanderson, lacks all signs of Stahl’s personal touch, particularly with lines he would more than likely never write on his own such as, “Boring women get a bad rap. There’s a lot to be said for boring women.”9

Stahl next briefly worked on the short-lived, Richard Grieco-starring 21 Jump Street spin-off, Booker, but he never received any credit for it. The co-creator of that series, Eric Blakeney, brought Stahl on board the next project for which he was a showrunner, Uncle Somebody. This intended series reunited Stahl with the man who helped get his foot in the television industry’s door, ALF co-creator Tom Patchett. The show was set to star Charles Fleischer, an actor best known for voicing Roger Rabbit, as a man who forms fourteen different personalities after getting hit on the head. Studio bosses, however, eventually forced the creative team to par it down to two personalities out of fear of appearing like they were making fun of the mentally ill. Stahl left the project after Blakeney was fired. Uncle Somebody never made it past the initial script development stages.

Stahl’s next television writing credit came in late 1990 and was for Twin Peaks, David Lynch and Mark Frost’s hit surreal, genre-bending mystery series that aired on ABC and is set in a small Northwestern town. Though Stahl felt that working on a Lynch production “was as close to dream-come-true as I had ever hoped to get in this hoary industry,”10 his drug problem was then raging and, for perhaps the first time that it truly mattered to him, it got in the way of his work. Stahl failed to complete his assigned script by its given deadline and, by different accounts, turned in a few disorderly pages that had hair and blood stuck to them. Stahl’s then-agent at CAA was less than pleased. Stahl miraculously still received a credit on the episode, whose writing was also credited to series regulars Frost, Harley Peyton, and Robert Engels.

Years later, when Stahl had years of sobriety behind him, he got the chance to work with Lynch again, only this time as an actor with a brief appearance in the filmmaker’s 2006 surreal digital epic, Inland Empire. Luckily, on Lynch’s part, there seemed to be no hard feelings about the past.

After Twin Peaks, Stahl received his last screenwriting credit for some time. The short-lived Shades of LA centers on a police detective (John D’Aquino) who can communicate with the spirits of the dead after surviving a near-death experience. Stahl received a co-writing credit in late 1990 for an episode titled Pointers from Paz, which centers on D’Aquino trying to restore the reputation of a fallen fellow officer who was believed to be corrupt. Though Stahl briefly met with Wes Craven about his short-lived series, Nightmare Café, his work never amounted to anything for which he was credited. It would be well over a decade before Stahl’s name appeared in another movie or television series.

A few years after his initial run as a television scriptwriter, Stahl commented, “Creativity is the opposite of TV. Creativity means sounding like yourself. TV means sounding like whoever wrote the pilot.”11 He also stated, “I was pathetically naive about caring. So, you pour yourself into a script and there’s a guy or a woman whose only job is to change every word you’ve written, so your name is on the script and the show is on the air and you’re mortified. I have a different attitude now, but that’s how I was. Perhaps the word is pretentious. Perhaps the word is stupid.”1 Stahl’s stance on screenwriting would, indeed, soften and evolve in the years to come when he would actually seem to enjoy making a very decent living at it.

Stahl made multiple failed attempts to get off drugs around the time of his last ‘90s television credit. As detailed in Permanent Midnight, when Stahl was in his late thirties, he went through the humiliation of working at a McDonald’s as part of his rehabilitation program. Stahl, needless to say, didn’t exactly gel with the golden arch work setting or the teenage coworkers who openly thought he was mentally handicapped.

Stahl continued battling with sobriety until he successfully kicked drugs in the spring of 1992 while he was staying in the garage of his colleague and friend, Eric Blakeney (whose 2000 film, Gun Shy, would feature Stahl in a small acting role). Though he had brief relapses afterward, Stahl never again fell as deep into addiction as he had throughout the ‘70s, ‘80s, and into the beginning of the ‘90s.

Hating With Love (1992-1995)

Now primarily sober, Stahl had next to nothing. Drugs had destroyed his security, his career, his marriage, and, for a short period of time, his relationship with his then-toddler daughter. In the summer of 1992, Jerry Stahl had nowhere to go but up. The television industry wasn’t exactly knocking down his door, anymore, so he slowly returned to conducting essays, articles, and interviews for a variety of publications. Amongst other things, he did celebrity articles for Los Angeles magazine, an ongoing column in Details that ran into the 2000s, and celebrity columns for Esquire and Outer Limits.

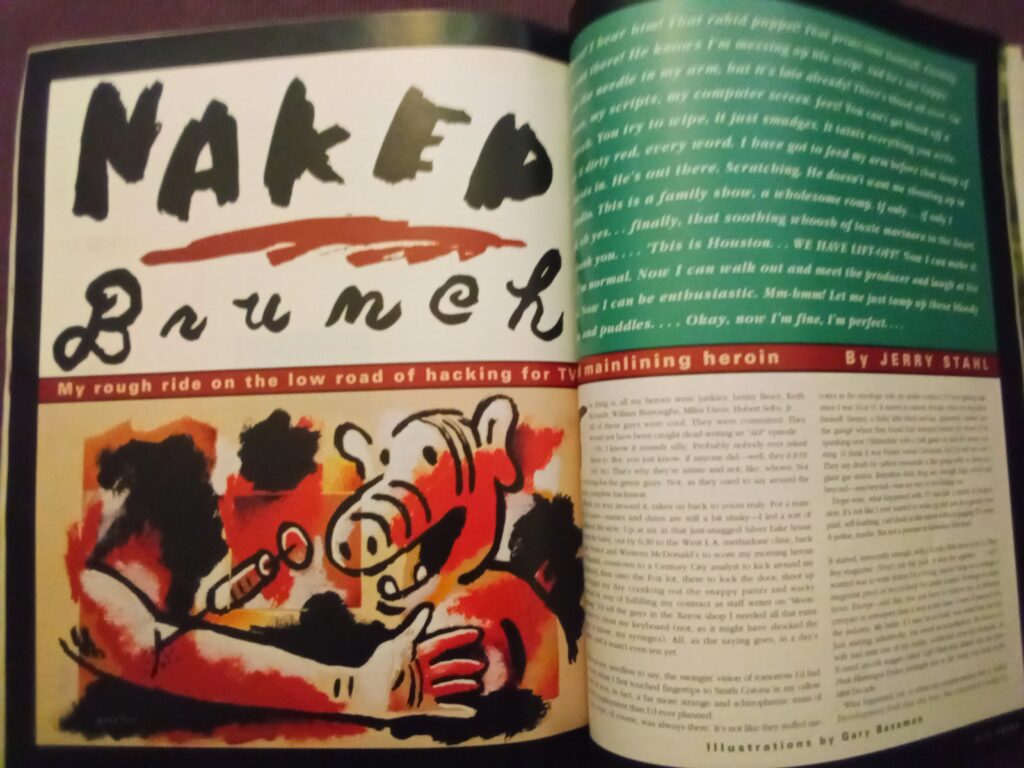

Most important, however, was a piece that Stahl wrote about his own life. Stahl had been living in what he describes as a crack house across the street from Musso & FrankGrill on Hollywood Boulevard. While going to the bathroom across the street one day, he ran into an old editor friend who worked for L.A. Style magazine and asked him what he’d been up to. After describing his recent travails, the friend was fascinated and encouraged Stahl to write about his experiences. Though it was rejected twenty-eight times by other publications, Stahl’s relatively brief account of maintaining his heroin addiction while writing for television and trying to appear as a semi-normal family man was eventually published by L.A. Style for their September 1992 issue.

The piece was titled Naked Brunch: My Rough Ride on the Low Road of Hacking for TV and Mainlining Heroin. Permanent Midnight fans should be interested to know that direct passages from the article later found their way into the book. Stahl opens the article with a darkly humorous description of shooting up in the ALF offices’ bathroom and hallucinating the alien puppet’s angry disapproval of him: “Oh Christ! I hear him! That rabid puppet! That prime-time hairball. Fucking ALF is out there! He knows I’m messing up his script. And he’s not happy… He doesn’t want me shooting up in his studio. This is a family show, a wholesome romp.”1

Stahl then tries to explain himself in the article, “The thing is, all my heroes were junkies. Lenny Bruce, Keith Richards, William Burroughs, Miles Davis, Hubert Selby Jr…. All these guys were cool. They were committed. They would not have been caught dead writing an ‘ALF’ episode… It was clear, a man would have to imbibe something on a regular basis to suffer this kind of success. If I wanted to make it in television, I sensed without knowing, I’d just have to roll up my sleeves…”1

Stahl also reveals in the piece that his then-snootiness towards his then-vocation led to a defiant attitude that only allowed his drug addiction to worsen: “By the time I hit prime-time level, I had this bad habit (no pun intended) of spraying a jumbo bloody Z on the tiles of whatever TV show I happened to be shooting up in. Kind of like an intravenous Zorro. It was, I suppose, my way of saying, ‘Just because I happen to be here, writing an episode of ‘thirtysomething,’ that doesn’t make me ONE OF YOU REEBOK PEOPLE.”1 Stahl goes on to confess, “There is, as any sane man can imagine, no real advantage to succeeding at something you loathe.”1

The piece also sheds light on the then-severity of Stahl’s addiction: “I was so far gone on the needle I’d go through nightly withdrawals, sweat through layer upon layer of sheets, towels, shirts and anything else I used to try and staunch the flow. Even if I could get to sleep, the shakes would wake me up again after a couple of hours. I’d have to shoot up again and slink back to bed.”1

The candid and wickedly hilarious voice behind Naked Brunch wound up gaining enough attention that it led to Stahl starting work on a memoir about his drug-fueled life up to that point. Though he was still struggling personally and professionally, he was unknowingly on the path to success again and, this time around, he’d finally be in the mental state to thrive with it.

Fighting to stay sober during this period, Stahl went so far as to attend AA meetings, something he previously had open disdain towards. At these meetings, Stahl met someone whose work he had greatly admired since his teenage years and who went on to have a profound impact on both his work and his private life.

Nicknamed Cubby, Hubert Selby Jr. was the author of such classics as Last Exit to Brooklyn, The Room, and Requiem for a Dream. In meeting his literary hero, Stahl recalls, “I said, ‘Hey man, it’s really weird meeting you because… your book was like the first one I ever, like, jerked off to.’ And he said, ‘Man, you’re sicker than I thought. What part?’”2

Selby profoundly challenged Stahl’s attitudes and beliefs and, at the end of the day, served as a positive influence on the still-struggling Stahl. Stahl stated, “I always believed that cliché that you had to be completely fucked up to write about fucked up stuff. And that was completely life-changing for me, to meet Hubert Selby Jr., realize that he was this, in his own tough, wiry badass way, a spiritual giant and, moreover, he explained the key thing to me, that both put me at ease and scared the shit out of me, which was, ‘Hey, man, once you get off dope and the alcohol, that’s when you realize how really dark you are,’ because there’s no buffer between it and you.”2

Selby offered what was, perhaps, his most invaluable advice after Stahl showed him the early pages of Permanent Midnight: “He was very generous when I was writing Permanent Midnight and I remember I showed him the first section… He said, ‘You know, it’s really great but one thing I would advise you to do… make sure that when you write about the people you hate, that you write about them with love.’”2 Stahl showed his gratitude for Selby’s advice by dedicating Permanent Midnight to him.

Shortly after meeting Selby, Stahl wrote a profile about him for Spin magazine. During this time, when he was also working on Permanent Midnight, Stahl briefly fell off the wagon and Selby spotted it instantly during an interview, laughed it off, and even gave him $40 for his next score.

Selby went on to show Stahl a great deal of support over the years of their friendship, even going so far as to supply promotional blurbs for Stahl’s first couple of published books. Selby would be an irreplaceable figure in Stahl’s life up to and after his passing in April of 2004.

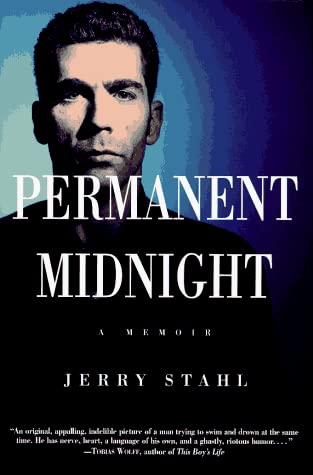

No doubt on edge with his, once again, sober state, Stahl threw himself into writing what eventually became Permanent Midnight. His first draft, typed on a cheap Australian knockoff of a Macbook, was unknowingly misspaced and came in at a hefty 1300 pages. Upon the completion of an early draft, Stahl got an agent who tried to sell it as a Julia Phillips/You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again/Hollywood insider type of book.

After a year of waiting, Stahl eventually let the agent go and sold the book to Warner Bros. Publications. Though they eventually helped make the book an enormous success, Warner Bros. editors first had to cut the manuscript down to less than a third of its original length. Stahl explained, “Huge chunks of Permanent Midnight were about just being a more-or-less-homeless sleazeball dope fiend in LA, but hundreds of pages had to be cut, and those were the pages. So my small run as a strung-out TV writer became the focus of the book.”3

In reading or writing about Permanent Midnight—or any of Stahl’s books, for that matter—it’s important to remember that the work almost always speaks for itself. Though Stahl claims to work almost entirely on gut instinct and emotion when he writes, there are still very specific events, ideas, themes, and feelings in his work that have the appearance of having been intellectually scrutinized by the author. Many of these elements would find their way into Stahl’s writing over and over again in the years to come. Permanent Midnight, first published in 1995, is where they all began. It laid the foundation on which Stahl’s true artistic voice was built (at least for the public to see). Everything that came after it is a result and an extension of it. Without the success of Permanent Midnight, Jerry Stahl’s wholly individualistic voice may have never found its way into the world unfettered and uncompromised.

Permanent Midnight is about drugs and Hollywood, sure. The hook of the book as it was released is that it combines the sordid details of hard drug addiction with a frank, gossipy, and devilishly entertaining insider’s take on what goes on behind the scenes in show business. All the details are all the more accessible and amusing because they are conveyed by Stahl’s frank, astute, and darkly hilarious voice.

Past the Hollywood tell-all aspects and the amusingly dangerous drug tales, however, Permanent Midnight is, like the majority of Stahl’s work, ultimately about pain. It’s about “a lifetime spent altering the single niggling fact that to be alive means being conscious.”4 It examines the inescapable “sense of difference, of being an outsider, that permeates all memory.”4 It provides painfully truthful details that, as Stahl writes, “make me want to pluck my eyes out and pound dirt in the sockets. There are stories you don’t want to tell, and there are stories that scald your brainpan right down to the tongue at the mere thought of uttering.”4 It’s a book, perhaps above all else, about being “crippled inside.”4 Stahl acknowledges in the book that his writing must face such pain head-on because, “If it hurts—if I don’t want to say it—then it must be true. That’s the only compass I have.”4

The book provides great insight into Stahl’s lingering pain over the troubles of his early family life. “My father. My father. I never thought of him. I never stopped,” Stahl writes, “My father who I have not let myself miss.”4 He also relays painful details of his “terminally tormented” mother who would “lay in bed in the dark for much of my childhood.”4 Stahl’s early family life ultimately “bred guilt as inherently as love.”4

Stahl also relays his hesitations and concerns about being so candid about the loved ones in his life: “this book is going to kill [my mother]. This book is going to push her over the edge… but so help me I don’t know what else to do. Not writing it is going to kill me.”4

Permanent Midnight, needless to say, also explores the many painful realities of a hardcore drug addict. It contains numerous stories of Stahl trying unsuccessfully to quit heroin, complete with accounts of withdrawals and visits to methadone clinics. In the grasp of addiction, Stahl writes that he viewed “life as a process of substituting fixes.”4 Drugs provided him with the numbness he needed to feel what other people would describe as happiness or normalcy: “there was all kinds of love floating around me, but it took the dose of opiates to let it out.”4

None of the book’s grittier aspects downplay the importance or the effect of its wickedly hilarious, straightforward, and insightful observations about show business, however. In Permanent Midnight, Stahl describes Hollywood as a place where “people are always offering you things. And as soon as they’re mentioned—even if the idea never occurred to you before—you feel like you really want them.”4 Stahl’s unflattering portrayals of many of his colleagues—from Edward Zwick to Mark Frost—are highly amusing. Stahl’s depictions of such people are oddly refreshing because they lack the standard showbusiness fakeness and forced politeness. Stahl uses the book to describe Hollywood exactly like he saw it and experienced it, just like he did with the other aspects of his life covered within it.

Permanent Midnight and its success had an extraordinarily positive impact on Stahl’s life and career. Though it took some time, he eventually found himself in a place where he could do the work that most mattered to him while also comfortably supporting himself with writing jobs that weren’t quite as personal. Stahl has few regrets about the book, though he has publicly stated that he wishes he hadn’t named some of the people he is unflattering towards in it. He’s also stated that he doesn’t mind the severe editing that took place between its early drafts and its publication, especially when considering everything the book, as it was published, has done for him. When he recorded narration for the book’s twentieth anniversary, Stahl stated it was hard for him not to cringe because of how much he’s grown and changed—both personally and artistically—since writing it.

Though Permanent Midnight is undeniably a bluntly confessional memoir, a hundred percent honesty is never entirely possible for anyone when they’re attempting to write about reality. There are simply too many consequences and too many concerns. No matter how honest Stahl was with his first memoir, there were still things he needed to say and face head-on. If Jerry Stahl was going to be completely honest with himself, he was going to have to write fiction.

The Pain Snob continues in part 3 of 7.

< 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources >