**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

Screenwriting Galore (2016-2019)

Though Jerry Stahl always seems to have an upcoming book in the works, the short time period that’s about to be covered is most notable for his return to and accomplishments in screenwriting. Stahl’s work, once again, was being produced, and this time with a short burst of regularity. It should also be noted that Stahl was wrapping up his time writing for Maron, which has already been examined in this piece, at the beginning of this period.

Urge, which was released in the summer of 2016, is an abysmally reviewed and little-seen film that took Stahl back to his independent cult roots. Stahl loved the concept of the film, was brought on board to rewrite other writers’ work, and wound up receiving sole screenplay credit. Director Aaron Kaufman, Guy Busick, and Jason Zumwalt received co-story credits.

The story of Urge centers on a group of friends who get together for a weekend on an island and end up partying at a mysteriously kinky nightclub that feels like a higher-budget (and less pornographic) nod to the one found in Café Flesh. The club also happens to house an insightful and fast-talking emcee who evokes memories of Flesh’s Max Melodramatic.

The group of friends is soon introduced to the devilish club owner portrayed by Pierce Brosnan, who also happens to deal a new up-and-coming drug called “Urge,” which unlocks primal urges in its users. Brosnan’s character evokes interest in the drug by making such statements as, “Imagine a key that unlocks that which is most hidden. Uninhibited by modern anxieties. Imagine being truly you… but just for a moment. A perfect creation.”1

The only catch to the drug is that if it is taken more than once, then it will have dangerously negative side effects. Needless to say, fans of the drug don’t listen to the rules and wind up paying some rather severe and brutal consequences. Brosnan’s character avoids all accountability when he says, “I didn’t sell anything. All Urge did was lift up the rock. What you saw was the wickedness and evil that laid beneath it.”1

Though its pacing is sometimes uneven and its execution is sporadically clunky, Urge is an overall underrated, inventive, and solidly made film that examines drug use in a whole new light. Director Kaufman successfully uses the film’s frequent nightclub setting and some aggressively executed filmmaking techniques to trippily externalize the effects of the characters’ drug use.

At its best, the film is a stylish, dangerously sexy, and bizarrely surreal madhouse of a movie that flourishes with its uncompromised and cynical view of humanity. As Brosnan’s character states towards the end, “If you had read the good book, you’d know that God created man in his own image. What they don’t tell you is the copy is nowhere close to the original. One can only conclude that people are simply… abysmal.”1

Stahl’s next screenwriting credit was for Chuck, released in the spring of 2017. The film is a biopic about the “embarrassing, humiliating, disgraceful, and completely mortifying clown show”2 that New Jersey boxer Chuck ‘The Bayonne Bleeder’ Wepner faced after impressively lasting fifteen brutal rounds in the mid-’70s against then-Heavyweight Champion Muhammad Ali. Wepner’s efforts, which inspired the classic film Rocky, brought him fame and attention for which he wasn’t at all prepared and which led to a downfall involving sex, drugs, and, eventually, prison time.

The film originated with The Devil and Daniel Johnston documentary filmmaker Jeff Feuerzeig. He had previously directed a one-hour documentary for ESPN called The Real Rocky, which told Wepner’s story. Feurzeig collaborated with Stahl on the screenplay in the early 2010s with the intention of Feurzeig directing it. Unfortunately, the film faced numerous production delays and took years to be realized. Feurzeig was eventually replaced by Philippe Falardeau as director and the script was rewritten by Michael Cristofer and lead actor/producer Liev Schreiber. The film was first titled The Bleeder, but eventually changed to Chuck because the producers feared the original title sounded like a horror film (though it was still released as The Bleeder in some European markets).

It is difficult to determine who should be credited for what on a screenplay that passes through the hands of multiple writers, but there are moments in Chuck that, at the very least, seem to have been penned directly by Stahl himself.

The first and, perhaps, most noteworthy of these instances is a scene in which Wepner’s strong-willed first wife (Elizabeth Moss) catches him with another woman. “He just falls in love… with the freckles on your ass,” the wife tells the woman. “You’re just the next person in line. The next person who looks at him like he’s something special… See, you think you’re special because of those freckles, right? And maybe you’d even marry him? And have a baby with him? And go through fucking hell with him? Year after year after year. Because you think, that’ll make it stick. That’ll make him yours. Just yours. Only yours. Forever. But you’re wrong. You see, you’re just so fuckin’ wrong.”2

Another scene, in which Wepner has an inebriated and disastrous parent/teacher conference, could have come directly from Stahl’s life before he got clean. “I’m gonna pray for you, Chuck,” his now ex-wife tells him afterward, using words that are possibly similar to those that Stahl heard during his darkest days. “I haven’t said a prayer since grammar school. But I am gonna pray that you find the strength to be a father to your daughter.”2

Chuck was given mostly positive reviews by critics when it was released, but it failed to garner much of an audience. It’s too bad, because the film, while not being anything groundbreaking, is a charming and insightful character study that also examines the toxic and fleeting nature of fame. It’s well made, has a number of wonderful performances, and offers a lesson on a fascinating public figure whose impact on modern culture is largely and unfairly unknown.

Stahl’s last produced screenplay credit, to date. is for the 2018 miniseries, Escape at Dannemora. The show, which stars Patricia Arquette, Benicio Del Toro, and Paul Dano, is based on the true story of a 2015 prison break that took place in upstate New York and involved two inmates and a female prison employee who helped them.

The series originated with industry veterans Brett Johnson and Michael Tolkin, who started working on the show while they were both still writing for the Liev Schreiber-starring Showtime series, Ray Donovan. After working on the project for some time with little source material, Tolkin and Johnson eventually were able to use a then-newly released Inspector General report on the prison break as their primary source. Once they were able to flesh out the story with more intricate details, Ben Stiller and his production company, Red Hour, became involved, with Stiller agreeing to direct all seven episodes of the miniseries.

Stiller brought Stahl on board the project as a consulting producer and as a writer on two episodes. Stahl was the only writer credited for the project aside from its two creators and he, once again, found himself working as a hired gun on someone else’s show. Despite it not being his creation, however, Escape at Dannemora’s frank and gritty style fit Stahl’s tastes quite well.

Stahl is solely credited for writing the third episode of the series. It is a very visual and atmospheric episode, with moments of blunt sexuality and some intermittent frank dialogue exchanges. In the episode, the two inmates plot their escape while one of them figures out a way to further manipulate Arquette’s character. “Give me one of your shirts,” Del Toro, who is sleeping with Arquette, tells Dano. “We got a bitch in heat and I want her to smell you, motherfucker… I wanna turn this from a two-way into a three-way. That way we got her on our side in a permanent way. So, give me one of your shirts.”2

Stahl is also credited for co-writing the sixth episode along with Tolkin and Johnson. The deliberately paced episode features a series of flashbacks that provide insight into what the characters did to get them to where they all are in present-day scenes. It’s a disturbing and emotionally complex episode that equally refuses to judge its characters or provide them with any false sympathy. Everyone, like the characters in Stahl’s most noteworthy writings, is painfully human and tragically flawed. The episode is brutal to witness, and it takes the great risk of losing its audience with its uncompromising nature. Though he didn’t write it on his own, the episode is the perfect fit for Stahl’s wise views on humanity and his empathy-laden depictions of downward-spiraling human beings.

It should also be noted that a good portion of the series happened to be filmed in Stahl’s hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. When he visited the set, Stiller put him in front of the camera and Stahl wound up having a cameo in the second episode as a man smoking a cigarette outside the exterior prison gates.

Escape at Dannemora feels like a gritty ‘70s production, just as Stiller stated in interviews that he intended. It exhibits bold and realistic filmmaking and contains layered characters that are impossible to define as any one thing. It’s a great accomplishment for all involved, and one that deserves all the positive reviews and awards nominations that it received.

In 2019, the Golden Globes, the Director’s Guild, the Screen Actors Guild, and several other groups recognized the miniseries with a number of nominations and a few awards. Just about every key player involved with Escape at Dannemora received a Primetime Emmy Award nomination, though the series didn’t wind up winning in any category. Stahl, after years of writing for television, received his first-ever Emmy nomination for his work in co-writing episode six.

Confronting Hell (2016-2022)

To backtrack slightly to 2016, Stahl then began work on what eventually became his tenth published book and third memoir. The project started as an assignment that was funded by the website, Vice, for a six-part series that was published in 2017. The Vice series and future book stemmed from Stahl’s participation in a 2016 bus tour group that visited concentration camp sites in Poland and Germany.

Stahl approached the material with humility, stating, “My heart is open. I’m one big emotion waiting to happen… Who do I think I am to think I can grasp the enormity of this suffering and honor it?”1 Stahl returned to similar subject matter that he had previously explored in Pain Killers because, in his words, “I think it goes to the core situation of being Jewish whether you want it to be or not.”2

Stahl stated of the decision to flesh out the material so it could be published by Akashic Books in the summer of 2022, “I thought there was a book in there—I wanted to find a way.”3 The main difference between the eventual book and the Vice series from which it originated is that, in Stahl’s words, “[Vice] didn’t want anything personal, mostly straight up reporting. Which is fine. But when I wrote the book, it morphed into this other thing.”4

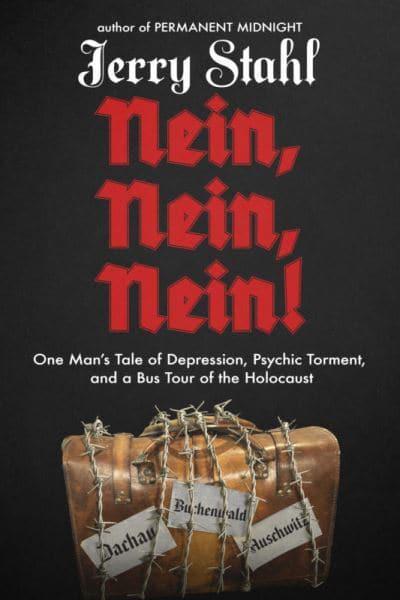

The finished book is titled, Nein, Nein, Nein! One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust. While it is obviously about the Holocaust, the book’s true subject is the effect that immersing himself in it had on its creator. Stahl acknowledges this in the book, writing, “There’s a certain arrogance in thinking you can say anything new about a subject so beautifully, deeply, and heartbreakingly chronicled by others. Which is why, he wrote defensively, all I’ve tried to do is focus on my own reactions—the what-it’s-like of it all.”5

Stahl’s book details his group visits to Warsaw, Auschwitz (the first actual death camp on the tour), Buchenwald (where inmates had been worked to death instead of being outright exterminated), Nuremberg (a former Nazi station), then Dachau (home of the first and longest-running concentration camp).

Stahl fills the book with a number of vivid and hauntingly powerful details from these visits. He describes an area that is filled with piles of deceased prisoners’ hair that was meant to be turned into rugs and other common household items. He also relays the sight of numbered hooks on which live prisoners hung while they waited to be cremated alive. Stahl stated about including such details, “It’s the specificity through which the enormity enters. You can’t believe [the Nazis] went to that length. And they did. And you can read about it.”4

A particularly haunting passage in the book reads, “I have just stumbled from one of the stained, airless chambers in which, seventy years ago, a million men, women, and children spent their last twenty minutes naked, foaming from the mouth in screaming agony, as prussic acid scalded their lungs until they asphyxiated. The corpses, I’ve learned, formed a pyramid. Victims struggled for their last inch of air beneath the ceiling. Parents tried to lift their children as high as they could. The top layer was always babies.”5

Just as shocking in their own way are Stahl’s observations about the camps becoming tourist attractions, complete with souvenir shops and snack bars. He writes in the book about visiting Auschwitz, “Perhaps the fallout from packaging horror for tourists—turning it to Auschwitz-land—makes a certain indignity unavoidable.”5 He later writes that “it feels vaguely wrong that the concentration camp experience doesn’t hurt” and that “this isn’t hell. This is the Museum of Hell.”5

Stahl states several times in the book that he struggled to come to terms with his true feelings while on the tour and that it was difficult for him to come to a singular understanding of the experience. At one point he writes, “Until you feel your feet on the ground, and consider the dead beneath them, until you inhale, and a voice in your head asks the question only visitors to death camps ask, Am I breathing air in which the ghost of human ash still lingers?—only then will you realize there exists but one certainty: that there is no way to comprehend the horror. And to assume you can actually dishonors those who endured it.”5

Stahl later writes, “I will say that on this trip I wanted to feel something, desperately. And perhaps because of this pressure, this sense of needing to Gandhi-morph, sprout wings, and ascend to lofty heights of camp-inspired love, I felt nothing. Or a kind of nothing. A temporary, let’s say, overwhelming emptiness.”5 He then concludes this thought by writing, “feeling overwhelmed and feeling nothing are not that different.”5

It being a Jerry Stahl book, Nein, Nein, Nein! does still manage to have its fair share of humor. Stahl depicts himself as a comical fish out of water amidst his fellow tourists, who hail everywhere from the Midwest to New Zealand. As uneasy as he is being around the other riders (the tour guide/authority figure who he typically butts heads with refuses to let him sit alone in the back of the bus), he is eventually endeared to them and certainly has a great deal of fun in describing and good-naturedly poking fun at some of them. Stahl doesn’t spare himself, either, as his personal mishaps (such as walking into a glass door or struggling to figure out his electronic luggage) are easily the book’s greatest sources of laughter.

Ever the inescapable artist, the finished book is as much a vehicle for Stahl’s self-expression as it is for Holocaust site facts and history. As detailed in the book, Stahl took the trip while in the middle of the collapse of his third marriage and while he was in the midst of a severe depression. The subject of depression was no stranger to Stahl and he, later in life, was able to fully realize that it was the true malady that had always haunted him and his work.

Going all the way back to Permanent Midnight, Stahl writes in retrospect, “I did not realize at the time that the real subject of [Permanent Midnight] was one I didn’t even mention, the one underneath all the spoon-and-needle action. The subject of depression. It plagued me then. Plagues me now.”5

Stahl further elaborates why he chose to start the project while in the middle of a deep depression by writing, “At least, face-to-face with the Giant Maw of Hell that was Eastern Europe in WW2, a guy would have something to justify that soul-deep desolation. For better or worse, antidepressants never worked. So instead of trying to banish the bad feeling—why not feed it? Give it a reason to live… Via my group tour, I hoped I could once more find relief in a situation where feeling miserable was appropriate.”5

Stahl sums up his concentration camp tour experience with strict realism, grounded hope, and uncompromising directness, writing, “I would like to think that the pain and suffering of the Holocaust and what we feel, confronted with it, can be a portal to ongoing agonies suffered by others. Be it plague, poverty, racial injustice, sexual abuse, bigotry, global warming, being unhoused, and on and on and on—it all happened, it never stops happening. You cannot compare pain. But you can have compassion, you can embrace the responsibility of doing something, anything, to comprehend and combat the horror that while not, overtly, yours, undeniably is. You can, by walking the topography of blood and screams, transform the abstract to the visceral. And do something.”5 He then adds, with typically blunt self-effacement, “You can, at least, if you’re a better person than me.”5

Nein, Nein, Nein tackles extraordinarily painful and dark subject matter, educates the reader on it, and, through Stahl’s candidly personal style and wittily satiric voice, still manages to be relatable and, for severe lack of a better word, entertaining. It’s as disturbing as it is heartbreaking, but it’s also, at times, as hilarious as it is endearing. Almost needless to say by now, it’s yet another Jerry Stahl book that can only be truly categorized amongst other Jerry Stahl books. It exhibits an endless variety of tones and emotions while effortlessly capturing the reader’s attention. It is a major and noteworthy accomplishment amongst a career’s worth of major and noteworthy accomplishments.

Nein, Nein, Nein! has been optioned by Robert Downey Jr.’s production company, Team Downey, for a potential film adaptation.

Today and the Future (2023-)

Through his writing, Jerry Stahl has repeatedly put his life on display to express himself, inform others, and create art. He is incapable of writing with anything but unflinching and devastating emotional honesty, though this is often balanced by his playfully pitch-black sense of humor. These qualities are what link his books together (along with some other pieces of his writing) and make them so unmistakably alive.

Knowing about his fascinating life only enriches his fiction, and familiarity with his fiction only provides further insight into his memoirs. The fact that he and his personal obsessions are, in one way or another, always the subjects of his books gives them a certain authenticity that is impossible to duplicate.

Stahl currently lives in Pasadena, California with his longtime girlfriend. He’s bored talking about drugs, he hates talking about ALF, and, despite the personal nature of his work, he tries to maintain his and his family’s privacy as much as possible. His books enjoy cult success in his home country, but are particularly beloved in Europe, namely France. Stahl once said of his success abroad, “Weirdly, my books do great in France. I always feel like some Dexter Gordon cat who doesn’t get the heat in his own country but who, over in France, is treated like a fucking rock star. It balances out.”1

Stahl always seems to be working on something. Writing is, simply put, the main addiction that he has fed for the last thirty years. He recently stated, “At my age, I’m a lot closer to a man being dead than being 40… so I’m writing like a man being chased.”2

Currently, Stahl is working on a secret screenplay and two books. One book is set in the same time period as I, Fatty and also tackles the subject of Old Hollywood. The other book has been in the works since the late 2000s and focuses on Sammy Davis Jr. and Donald Goines in ‘60s and ‘70s Los Angeles. Stahl has also collaborated on a potential graphic novel with his French book translator and The Killer graphic novel author, Alexis Nolent, but the status of that project is currently unknown.

Whatever is next for Stahl, there is no doubt that it will be bitingly hilarious, painfully vulnerable, cynically romantic, boldly courageous, unflinchingly honest, shockingly frank, personally revealing, perversely kinky, endlessly fascinating, thought-provoking, vomit-inducing, squirm-producing, and beautifully heartbreaking. It will be every bit as brilliant and inescapably cracked as its creator. And, like a red-hot branding iron that can somehow reach inside the ears, it will stay scalded on its reader’s psyche for as long as they can retain conscious thought.

If it were any other way, then it most likely wouldn’t be written by Jerry Stahl.

< 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources