Part Eight: Gone is Malcolm Poe

Gone was Burnett’s first-produced spec screenplay in over a decade. On paper, it seemed to be an amalgam of all the strengths his work exhibited to date: great characterizations, a strong female lead, sparse and true-to-life dialogue. Perhaps even more appealing, it was all neatly and cleverly wrapped up in an intense, commercially viable genre package.

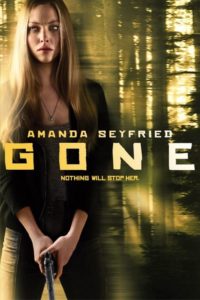

Gone (2012)

Gone centers around a young woman named Jill. When her sister goes missing, Jill is convinced her sister was abducted by the same serial killer Jill escaped from two years prior. Unable to prove she is anything but a paranoid former victim, Jill is forced to face her demons, hunt the killer down, and save her sister, all on her own.

The script was sold to Lakeshore Entertainment in October of 2010. It quickly landed Amanda Seyfried for the role of Jill, and was in production by April of 2011. Burnett calls the turnaround time a “land speed record.”

Burnett originally intended Gone to be a gritty and disturbing R-rated thriller. Jill was a victim of PTSD, driven insane by her obsessive need to find her sister and face her past. Burnett, Seyfried, and director Heitor Dhalia wanted it to be the next The Silence of the Lambs. The producers wanted to reach a wider age range, however, and unwisely guided Gone towards a PG-13 rating, compromising it from the start.

Burnett’s script remained entirely intact for the final cut of Gone. However, the film once again featured a recurring problem found in productions of Burnett’s screenplays, one that usually holds them back from greatness: the tone. The finished film softens the action by depicting the script’s more intense events with a glaze of disconnect and indifference. As Burnett recently stated: “When your heroine fights for her life in the mud and comes out with clean hair and skin, there’s a problem.”

While Seyfried has proven herself to be an extraordinarily gifted actress over time, her performance in Gone never goes beneath the surface. Her PTSD is neither explored nor lived in, much like most of the other important details in the film. Everything about Gone feels rushed, under-discussed, and impersonal. That being said, there is a pervading quality to the film that occasionally makes it rise above its otherwise average, though by no means bad, presentation.

Gone, not fully committing to any one style or intended audience, failed to form a reception of note upon its release, earning just $11 million domestically. Mike McCahill of The Guardian called the film “surprisingly watchable multiplex filler” and stated that “Allison Burnett’s screenplay parcels out brisk character notes with its twists”.

Obvious issues with the film notwithstanding, Burnett still likes Gone and thinks it could still have its day in the sun. Young women, in particular, continue to give the film small shout-outs of support on social media.

The Escape of Malcolm Poe (2014)

Near the end of the 2000’s, Allison Burnett found himself looking back at his life. He was a middle-aged family man, successful in a career for which he had once risked everything. He thought about friends who hadn’t taken the same risks, those who had compromised their lives for whatever reasons. He thought about his future, getting older, his own mistakes, and what might have been had he not gone down certain paths and chosen to go down others.

Out of these ponderings came his next novel, which Burnett started writing in the winter of 2010, and completed the following summer. The book’s protagonist, Malcolm Poe, is a middle-aged man unhappily married to an upper-class woman from a prestigious East Coast family, not unlike Burnett’s first wife. When his youngest daughter leaves for college, he goes off his antidepressants, leaves his job, and commences the realization of his fourteen-years-in-the-making plan to escape his life and become a writer.

Poe’s first-person narration is inescapably curmudgeonly. His observations are tired, disdainful, and often hilarious views on humanity: “What is it about elderly WASPS and dandruff? Is it genetic or learned?”. He is simultaneously spot-on and delusional, justifiably and astutely cynical, but also filled with anger he is unable to own. During Poe’s misguided adventures working a suicide hotline, he becomes so disgusted with a caller that he tells her she’s a “pig” right before hanging up on her.

Poe is witty in his sarcastic inner criticisms of others, but narcissistic in his inability to see similar faults in himself. In other words, he’s a classic Allison Burnett character: ineludibly broken, passionate in thought, but always misguided in direction.

Much about The Escape of Malcolm Poe is classic Allison Burnett, as it almost reads like the consummation of his strengths as a writer. Like Christopher, The House Beautiful, and, to a certain extent, Undiscovered Gyrl, Poe takes on its own “meta” awareness– it is as much about the act of writing as it is about the humanity and stories of its characters.

Like many of Burnett’s creations, writing is both Malcolm’s salvation and damnation. On one hand, the written word for Burnett’s characters will always be, as Glenn says in Ask Me Anything, “as close to the angels as I get.” On the other, it always seems to be the thing that cuts them off from living a real life, as well.

The book is Mr. Poe’s explanation of why he’s escaping his life and throwing himself into solitude for the remainder of his days. He is a man tragically unable to connect with another human being, and his only (perhaps unconscious) hope of doing so is through the loneliness of writing. How he fights his increasing awareness of this is the heart of the character and the novel, providing both the dark humor and the tragic drama of this bitter, self-alienated man.

Also in classic and expert Burnett fashion, the reader comes to a full and complete understanding of the book’s narrator in its final moments. Described as the “Burnett Epiphany” in previous sections, this calculated flooding of information and emotion is as effective and heart-wrenching as it’s ever been in Burnett’s work.

We ultimately come to know why Malcolm is the way he is and we feel for him. We understand him, relate to him– not because we like him, but because his humanity, however flawed, is so fully developed and realized. And because he is honest– at least with everyone but himself.

Another Hard Sell

The Escape of Malcolm Poe is sophisticated, daring, politically incorrect, and isn’t afraid of alienating anyone. It is quite possibly Allison Burnett’s most accomplished piece of writing to date. If Undiscovered Gyrl is something of a modern-day Catcher in the Rye for teenage girls, then Malcolm Poe is Burnett’s answer to a modern-day, middle-aged Holden Caulfield.

For all the same reasons that make it great, sadly, no one was interested in buying it. Burnett held onto the manuscript for four years with hope someone might take interest. He had received plenty of support and compliments, but publishers were reluctant to try to sell the story of an unlikable, middle-aged misogynist to modern-day readers. Richard Abate, the primary force behind Undiscovered Gyrl’s publication, told Burnett that though he felt it was a “beautiful book” he did not “have the stomach” to try to sell it in today’s marketplace.

Passages like the following, in which Poe is observing his wife, support fears that the book could turn off mainstream readers but also prove that its frank, politically incorrect humor is easily lost on many:

“Although she is fit and pretty, her chin is beginning to sprout tiny hairs. They are only visible in direct sunlight, but will soon haunt my days and nights. Worst of all, she is always upbeat and encouraging.”

Burnett once again relented as he had done with Death to Sunshine, swallowed his pride, and gave the book to Writer’s Tribe for publishing. Burnett self-promoted the book with little success to date, explaining:

“…when it finally got published by a tiny publisher, it was a non-event. I rented a place and did a short reading and Q&A, then paid some book event guy 6K to help promote it. He did less than nothing.”

Our piece on Allison Burnett will conclude with Part 9, which will focus on the production of his adaptation of Undiscovered Gyrl and second directorial effort, Ask Me Anything, his self-published novella/Undiscovered Gyrl sequel, and his screenwriting career today.