**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

Moving Forward While Looking Back (2004-2007)

Though Jerry Stahl was successfully fulfilling his dream of being a novelist at this time, his bills were primarily paid by the many screenwriting jobs that he was then assigned. He continued to do script doctoring work on projects like frequent collaborator and friend Philip Kaufman’s 2004 thriller, Twisted. Like the majority of all working screenwriters, however, most of the scripts that Stahl wrote on his own went unproduced. The unmade scripts that Stahl penned during this time include a pilot for FX called Junkboy, a remake of the 1981 Burt Reynolds-starring cop thriller, Sharky’s Machine, and a Jerry Bruckheimer-produced comedy about a handler who is assigned to keep a rock star off drugs called The Minder.

One of Stahl’s favorite unmade projects, a biography of concert pianist Oscar Levant that focuses on his life and work after a mental breakdown, was written during this period for Ben Stiller’s production company. Stahl was also hired by Johnny Depp’s production company in 2006 to co-adapt, along with filmmaker Terry Zwigoff (Crumb, Ghost World), a French novel by Laurent Gaff called Happy Days, which is about a young man who visits a nursing home and falls in love with one of the residents.

Stahl was also doing some community work at this time, as he then stated, “I’ve been teaching at a juvenile hall once a week, working with gangbangers waiting to turn 18 and get sent away for a couple of decades. And that’s been as rewarding as anything I’ve done my entire life. Hearing those gates lock behind when you walk out gives you a whole new vision of reality. These guys occupy a parallel universe few white people get–or care–to glimpse.”1 Footage of Stahl teaching his students was recorded for and included in a Discovery documentary series by filmmaker Bruce Sinofsky called San Quentin Film School, which was released in 2009.

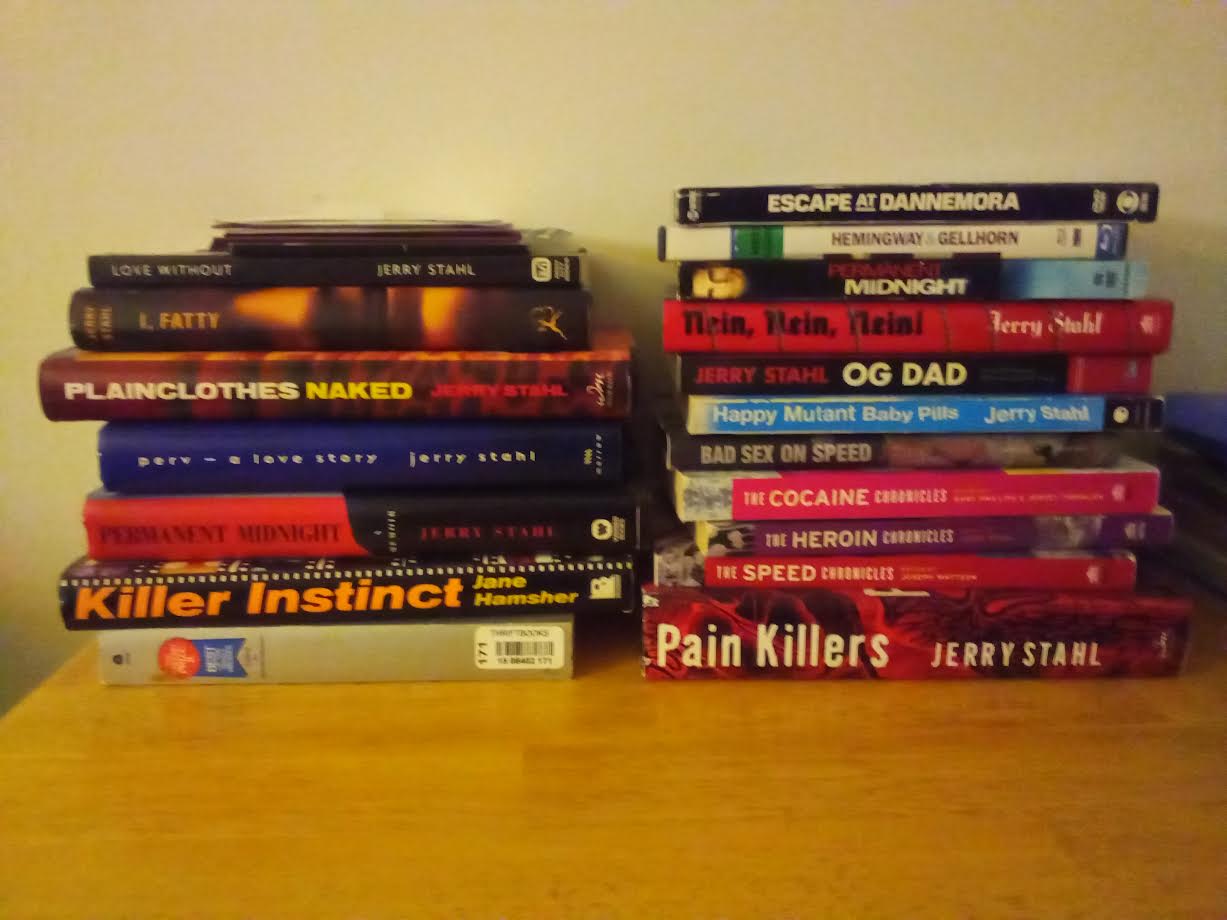

At the end of this period, Stahl had his next book published. Originally titled Uncool but changed at the last minute before its release in the summer of 2007 to Love Without, the book is a collection of eleven of Jerry Stahl’s short stories. Most of these stories had been previously released in various publications over a span of nearly thirty years. Love Without is a telling and fascinating collection that reveals both where Stahl had been artistically and where he was then at presently.

The Age of Love first appeared in the anthology, Unnatural Disasters, in 1996. It features a fourteen-year-old boy taking an airplane ride to visit his sister. While on the plane, he sits next to an older woman whose husband invented the panty shields that she is wearing and that the boy winds up fingering. The story reads like an early variation of Perv, with references to the boy’s mentally ill mother and her visits to Western Psychiatric: “The truth is, my mother’s bedroom habits were another reason for this trip… my mother had started ‘staying in’ again… ‘staying in’ was family code for not getting out of bed. For not washing up or getting dressed or doing much of anything but staying horizontal and shouting out peculiar comments or requests for food.”2

Cossack Justice first appeared in Quarry West in 1979 and centers on a young boy who has lost his mother and is then sent to a boarding school by his guardian aunt and uncle. It, again, covers similar themes and emotions to those found in Perv, though Cossack Justice’s main character exhibits younger and more innocent qualities than that book’s protagonist. The boy goes on to develop a friendship with his trouble-seeking and relatively world-weary roommate, who also happens to be the son of a Russian prince. This early piece of fiction suggests that Stahl was still experimenting with ways to quell the pain of his childhood through writing, as both boys in the story exhibit clear autobiographical qualities of their author. Interestingly enough, it’s the roommate, a secondary character this time around, who loses his father to suicide.

Gordito was first published by Open City in 2006. It’s an oddly touching and equally absurd character study that centers on the narrator’s (a former junkie) relationship with an alcoholic, hepatitis-suffering little person named Puray, who grew up with a circus family and performed in freak shows as a child. The narrator sums up their relationship and himself by stating, “I know about mutants. The women they end up with. Women you want in private… When what you get is a Puray… You get a mutant, beautiful or not. And you love them. Because they’re just like you.”2

The Somnambulist’s Wife first appeared in Quarry West in 1979. It features a wife who tries to get her former boxer, dementia-suffering husband help through the aid of a televangelist. Desperate for her husband to return to normal, she heartbreakingly states, “Maybe the only time he was really with me was when he slept.”2 She then provides further insight into her troubles and her devotion to her husband: “When he hurt or ruined, when he collapsed or laughed or loved me in his odd way through some hollow dawn, I bent myself to the shape of his need. No matter who or what he was, I was transformed.”2

Jigsaw Music was initially published by Quarry West in 1980. It features a woman named Lorraine who meets her next-door neighbor in her apartment building, a man who consistently disrupts her peace with his use of a jigsaw that he keeps hidden and uses to create small, ornate objects. She soon discovers a peephole in one of his walls that allows him to look into her apartment. Typical of a Jerry Stahl protagonist, the discovery makes the ashamed woman think of her mother: “[Her mother] told Lorraine about a girl in high school… She had been slovenly about herself… Because the girl was not careful with her things, the boys all knew her secret thoughts… Lorraine grew up feeling that sometimes the men around her could see inside her, and that, when they did, it was her fault always, for being slovenly about herself.”2

I’m Dick Felder! was first published by Playboy magazine in 1985. The title character is a middle-aged dentist who, unsatisfied with his home and sex life (his frigid wife inexplicably calls him Elroy in bed), has a mini-breakdown and leaves his work and Buick Regal behind to travel in a van with a runaway teenage girl and her kid brother and sister. The story fully displays Stahl’s disdain towards the lifestyles of privileged white middle-class Americans. Felder is the type of hopelessly square, unknowingly hypocritical, and otherwise wholly clueless character that “did not want to get in trouble”2 and that Stahl likes to endlessly poke fun at and satirize in his literature.

L’il Dickens first appeared in LA Weekly in 2007. Simply put, it’s about its narrator’s homosexual encounter with Dick Cheney in a gun and ammunition store. Opening up with the sharply straightforward line of, “I did not mean to sodomize Dick Cheney,”2 the story just gets more graphic, hilarious, and wickedly, absurdly satirical as it progresses. When the narrator relays things like, “[Cheney] reached in my pants and chuckled that he’d found the weapon of mass destruction,”2 it’s hard to keep reading through the heavy, shock-inducing laughter it begets.

Finnegan’s Waikiki was first published by Playboy in 1986. The story involves a man who makes a living writing coupons and his visit to a swingers and nudists’ colony (something Stahl once reported on in his early journalism days) where his ailing father (a former gossip columnist) stays. While there, the man gets to know his twenty-something stepmother, Bambi, as he takes in the community and the lifestyle within it. Perhaps the story was a way for Stahl to have the communications and eventual peace with his late father that he never got to experience in reality. Stahl’s protagonist, this time around, gets a touching apology from his father that other Stahl characters are often denied: “I want to make it up to you for all the times I was out carousing when you were stuck home with your mother.”2

The Twilight of the Stooges first appeared in the anthology, The Cocaine Chronicles, in 2005. The story involves a narrator who finds himself blowing cocaine into his widowed female dealer’s anus while televangelist Jimmy Swaggart internally speaks to him. The story, or self-described “snippet from a loop,”2 is cringe-worthy, revelatory, and shockingly hilarious. It includes a telling and fitting observation that could only belong to Jerry Stahl: “I don’t have memories. I just have nerves that still hurt in my brain.”2

The next story in the collection, Pure, contains characters and themes that would be largely present in Stahl’s next novel, Pain Killers. The story centers on the thoughts and observations of a Christian sex worker that is employed by a pastor-run escort agency called Christian Fun Girls. The lead character, with her nonlinear and meth-influenced wandering mind, experiences infused thoughts of her past, present, and future (not dissimilar to the first-person liquid linearity found in Perv) as she makes a trip to the doctor. She considers herself to be a virgin because she abstains from vaginal intercourse and only provides other forms of sex to her clients. Her motivation for staying a virgin is explained directly: “When Christ returns, abstinents will have the first seat on the chariot to salvation.”2

The last story found in Love Without sticks out not only from this particular collection but also from Jerry Stahl’s entire body of work. Titled On Water Shoulders, the story is, arguably, the most vulnerable and nakedly sincere piece of writing he’s ever published. It features uncharacteristically warm yet undeniably bittersweet and somewhat disturbed depictions of childhood memories and feelings. Consisting of third-person, dream-like observations by a young boy about his family life, the story drops Stahl’s normally present sarcasm and typically biting satire for something more directly truthful, emotional, and artistically profound.

The child of On Water Shoulders is acutely aware of the feelings of dysfunction and illness that are constantly surrounding him in his home, but he never experiences them first-hand. While there is much comfort and beauty to be found in the story, it’s always offset by the undercurrent of darkness that the young boy’s awareness creates. The story opens with the sentence, “Without knowing why, Morton believed that his parents were imposters,” and later relays, “His parents changed out of their masks in the other room when he was not with them, when he turned around they took off their faces.”2 Despite the child’s obvious love for his father in the story (the feelings towards his mother are a bit more complex and negative), he struggles to find peace or security when he tries to fall asleep at night because he knows that something is terribly and irreparably wrong beneath the surface of his life.

Killing Pain (2007-2009)

One of Stahl’s most noteworthy screenplay jobs during this period was adapting Jeff Henderson’s memoir, Cooked: From the Streets to the Stove, From Cocaine to Foie Gras. Though the film was never made, Will Smith was attached to star as Henderson, a well-regarded fine dining chef who learned to cook while serving a prison sentence for dealing crack cocaine.

Around this time, Stahl also worked with friend and frequent future collaborator Marc Maron on a proposed series for HBO, but that project also never found its way to production.

Keeping himself busy with numerous side projects, Stahl also contributed to a Los Angeles Times serial novel that was titled Money Walks and started a blog on The Rumpus called Post-Young, which focuses on Stahl’s fiftysomething view of the world. Stahl states his hopes for the quality of the blog in his introductory piece for it: “A great blog, for my money, is one with just enough patina of cultural relevance to make it seem like the blogger is not really some self-obsessed jim-jim eating his arms and calling it dinner. It’s not about them, it’s about the zeitgeist.”1

Most consuming for Stahl, however, was the work he was then putting into what eventually became his sixth published book. Appropriately titled Pain Killers and released in the late winter of 2009, Stahl stated in previous interviews that he had been working on and researching the novel, which was “about a certain death camp Doctor,”2 since as early as 2003.

Josef Mengele, a physician at Auschwitz who administered deadly gas to and conducted inhumane experiments on prisoners, had fascinated and terrorized Stahl’s psyche for years. Shortly after starting the project, Stahl found that writing about Mengele was harder for him than he initially thought it would be. The exceedingly dark subject matter got to him and it took Stahl a couple of years to figure the book out, as he struggled with its voice and style. Stahl remedied his issues and frustrations by combining his research and ideas with old, familiar, and comforting characters: Manny and Tina, the damaged lovebird protagonists from his earlier novel, Plainclothes Naked.

Stahl stated about the decision to bring already-established characters into his latest novel: “I had no real plan in mind. I wanted to write about Mengele, but fifty pages in I realize I was in danger of cranking out ‘I, Mengele.’ A book for which I do not believe America is crying out. Manny was a way in. Something to hang the story on.”3

Stahl even went so far as to give Manny a teenage daughter and a past that involved the suicide of his father in the new book, both of which were previously unmentioned in Plainclothes Naked. On top of this, Manny has a moonlighting job as a movie consultant, stating in the book that “a studio executive would pay money just to sit in a room with somebody who once sat in a room with somebody real.”4 Manny is also suffering from Hepatitis C and describes it as “like having an old-fashioned anarchist’s bomb implanted in your liver, waiting for the fuse to run down and blow you into full-blown cirrhosis, then over the finish line to cancer.”4

All the above choices paralleled Stahl’s life when he wrote the book, and it is clear that he was trying to personalize it as much as possible in order to provide a buffer to the more disturbing and impersonal details involving Mengele.

Manny, who first-person narrates Pain Killers (opposing the third-person narration in Plainclothes), is now an ex-cop. He is hired to go undercover and pose as a drug counselor at San Quentin (recalling Stahl’s own experiences of teaching at juvenile hall) to see if a 97-year-old man claiming to be Mengele is actually who he says. ‘Mengele’ “wants credit”4 for his past infamous deeds and, we discover, is presently working for a pharmaceutical company by conducting tests on prison inmates. It turns out, he was incarcerated for a hit-and-run incident that occurred while he was hauling Animal Control lab equipment in the back of his van.

Nazism, drugs, madness, damaged relationships, agents of the FBI, and a Christian escort agency all eventually become entwined in Stahl’s most ambitious narrative to date.

A large part of the joy of Stahl’s writing comes from reading how his characters internally react to the world around them. Manny’s first reactions to San Quentin, which is the size of a “small city. Four hundred and seventy-three acres,”4 are typically insightful. “A blue and white sailboat floated out in the bay, in some shimmering world that had nothing to do with this one,” Manny observes. “The outs. I wondered if the sailboat people knew that they were half a mile from the Hillside Strangler and 317 other killers with nicknames, professional and recreational.”4

Tina, now Manny’s ex-wife, becomes part of the story due to her involvement with a Jewish Aryan gang leader in the prison. She is first introduced in the story when she is seen in a trailer near the one in which Manny is staying. Appropriately enough, Manny watches her through the window as she stubs out a cigarette on a tattooed, muscle-bound inmate.

The reunion that follows leads to much inner turmoil within Manny, something that is communicated with typical Jerry Stahl insight and wit. Tina, it turns out, left Manny due to his moodiness and anger and had previously resorted to bulimia to help quell the pain of living with him. Manny bluntly observes, “she had to puke herself numb just to tolerate my company. Being born a Jew, guilt stuck to me like Velcro.”4

Manny explains his and Tina’s passionately bumpy relationship by stating, “Once you saw how your wife killed her husband [the event that introduced her character in Plainclothes Naked], you lived with a certain back-of-the-head hum. You knew what could happen. You’d seen the evidence. But still… You didn’t think about it. Not all the time… If you were fucking a beautiful woman on the edge of a cliff, would you look down the whole time? Or would you look at her? By definition, if a woman is beautiful enough for you to fuck on a cliff, she’s beautiful enough to make you forget to look down.”4

Manny tellingly sums up being in love with Tina when he says, “That’s the thing about being attracted to a borderline personality. I found myself doing things normal people didn’t do, and going along, because I was a borderline personality.”4 Perhaps most revealing is when Manny simply states, “The drug I was addicted to was Tina.”4

While studying the paperwork on his future drug counseling group members, Manny comes across some notable quotes from ‘Mengele’ (officially booked as Fritz Ullman) regarding his cause, such as “There are two ways to save the race: by eliminating lesser races and enhancing the superior one.”4

Manny goes on to provide some social commentary on the history of Nazi genocide, pointing out that President Roosevelt refused to help and that “The horror, for the Jews, was that it was Jews who were being exterminated. The rest of the world—including America—was more or less okay with it. Until the very end.”4

It should be noted that one of Pain Killers’ many aspirations is to shed light on America’s rarely mentioned collaboration with the Nazis. Stahl said at the time of the book’s publication, ”I think if you read the book, you’ll see that a lot of the Nazis, including Mengele, there’s something very American about them. In fact, a lot of his research was paid for by American money, the Rockefeller Foundation. That’s a thrust of the book—it’s not really ‘not-American.’ A lot of Nazis and Nazi sympathizers were American.”5

When Manny starts his drug counseling group, which mainly consists of hardened criminals and/or gang members, he couldn’t be more out of his element. Always the addict, he is hung over for his first group session since, the previous night, he came upon near-hundred-year-old morphine in his trailer and injected it without thinking twice about it. “Until that moment, I had not been thinking about drugs,” Manny explains, “But as soon as I saw them, I needed them.”4 Manny stumbles through his first session by throwing out bumper sticker-like slogans that make him sound as square as he feels: “Definition of a junkie: guy who steals your wallet, then spends an hour helping you find it.”4 ‘Mengele’ does little in the group but rant about his demented cause, which makes Manny all the more uneasy.

The most absurdly amusing aspect of the novel involves Tina’s association with a character known as Reverend D, who happens to run a Christian escort agency (recalling Stahl’s previously mentioned short story, Pure). “[The escorts wouldn’t have sex] vaginally. But they would do naked prayer sessions. Along with Greek, Russian, bareback oral or facials,”4 Tina explains to Manny. “My vagina is a gift from Jesus!” an inebriated escort from the agency ecstatically and proudly proclaims at one point.

As the story progresses, the reader is treated to a number of profound moments, like when Manny says to Tina, “We’re our own medical experiments: you emptying your body, me filling mine up with cut chemicals and Mexican smack.”4 The pair are forever trapped by their own damage, their own personal Holocaust, unable to fully live with or without each other and, quite possibly, destined to make the same mistakes for as long as they live. Manny and Tina are, perhaps, Stahl’s embodiment of history repeating itself, one that compulsively (and proudly) carries out the so-called depraved, filthy, and flawed ideals against which Mengele so drastically and inhumanly fought during the Holocaust. “Until it happens again,” Manny states towards the end, quite possibly referring to both his personal life and to history.

As for whether or not Manny will return in any future Stahl novels, his creator stated, “I love the character, but in all honesty, the nation is not pounding on my door, begging me to march Manny out again.”3

As stated previously, Pain Killers is the most ambitious and, by a small margin, the longest book that Jerry Stahl has written to date. It’s also, without question, his busiest, so much so that it’s extraordinarily difficult to summarize with any simplicity. Occasionally, the book topples under the weight of its own ambition and narrative complications, as its many conflicting tones and elements don’t always come together easily or organically.

Though Pain Killers is, overall, perfectly entertaining and enlightening, it’s not as effortless of a read as Stahl’s previous books. It is more complex, more challenging, and needs to be read in multiple sessions in order to be fully absorbed. That being said, the book does manage to come together in a highly satisfying manner in the end. The road getting to its eventual destination is a bit unsmooth, but the book is ultimately as rewarding and thought-provoking as anything Jerry Stahl has ever written. It simply demands a bit of openness and patience from its reader.

Pain Killers was optioned by Seinfeld producer and Borat director Larry Charles. Stahl and Charles, at one point, shared the same manager, who also represented Jack Nicholson. Though it didn’t pan out, there were discussions about Nicholson playing Mengele. Stahl and Charles spent a good deal of time trying to turn the material into a feature-length movie, then tried to turn it into a potential series titled Manny & Mengele. Though the adaptation never came to fruition, it did open the door to a close friendship between Charles and Stahl that led to future creative collaborations.

Stahl met the woman who would become his third wife while on a book tour promoting Pain Killers.

Gellhorn & Hemingway (2009-2012)

Stahl’s screenwriting career would reach new heights of respectability during this time period. One of his most known and noteworthy unproduced screenplays was written around 2011. The Thin Man, based on the novel by Dashiell Hammett, had already been produced as a mystery/comedy feature in 1934. The story centers on an alcoholic former detective who teams up with his wealthy socialite wife to solve a murder. Johnny Depp, who had previously been attached to star in other unmade scripts written by Stahl, was responsible for bringing him on board the project. Warner Bros., the studio behind the film’s development, wanted the film to retain its period setting but also have a contemporary feel. Because the studio wanted more action in Stahl’s script, he was eventually replaced by two other writers before the project was officially aborted.

Before his Thin Man assignment, Stahl spent roughly three years working with director Philip Kaufman on what would become the screenplay for the feature film, Hemingway & Gellhorn. As previously noted, Kaufman and Stahl had before worked together on other projects. They were rather close at this point, and Stahl stayed in hotel and motel rooms (depending on the budget) in Kaufman’s hometown of San Francisco for extended periods of time in order to work directly with his mentor, father figure, and friend. Stahl, who also considered Kaufman to be his own personal film instructor, often found himself writing and discussing the script in Kaufman’s home basement.

Though he is credited as a co-writer for the film alongside Barbara Turner (who passed in 2016), the screenplay was actually entirely written by Stahl, himself. Turner had initially concocted the idea of the film and wrote an enormous script that Stahl never read. Presumably because Turner and Stahl had overlapping historical scenes in their scripts, Turner also received a full-on writing credit as a technicality. Working solely with Kaufman, Stahl often had to think of creative ways to write scenes around existing historical stock footage because the film would be produced on a rather tight budget.

The film centers on the torrid romance between writers Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn (Clive Owen and Nicole Kidman) as it is relayed by Gellhorn in future-set scenes. When the audience first sees Gellhorn, she is an older woman who still has fire in her gut. Her opening lines set the stage for her exceptionally tough character: “Love…? Whoa. Huh. Must we? I was probably the worst bed partner on five continents. All my life, idiotically, I thought that sex seemed to matter so desperately to the man who wanted it that to withhold it was like withholding bread. An act of selfishness. And all that bread isn’t worth a hoot in hell… What’s always really absorbed me about life is what’s happening on the outside. Action. Now that–that was something to be shared. I’ve always felt most at home in… the most difficult places. But love? I’m a war correspondent. Of course, there are wars. And there are wars.”1

Hemingway and Gellhorn’s relationship develops while they both serve as war correspondents for the Spanish Civil War until the late-1930s. Hemingway, who is introduced in the film by stating that “everything dies”1 before bashing in the head of a large fish, behaves in a way that would today be described as extreme toxic masculinity. He lives a hard life that revolves around drinking, fucking, shouting, fighting, writing, and protecting his fragile ego.

Gellhorn, the more stable of the pair, can more than hold her own in heated conversations, which delights Hemingway endlessly and wholly endears her to him. “Gellhorn, you inspire the hell out of me” and “You’re more of a man than most men”1 are amongst the compliments he endearingly and passionately bestows upon her.

Gellhorn falls for Hemingway on the battlefield after she witnesses him whispering gently to a dying man in the midst of gunfire and explosions. She observes, “It’s hard to say exactly the moment you fall in love with someone. But I knew with him the exact moment when I knew I had. And I knew why. In that instant, it was his words. The ones I would never hear. Whatever private thing he uttered.”

The two eventually marry, though the marriage suffers and eventually ends due to Hemingway’s increasing insecurity about Gellhorn’s successes, abilities, and talents.

Towards the end of the film, Gellhorn discusses covering the first Nazi concentration camp in Dauchau after her time in Spain. How she describes it not only provides insight into her character and history, it also provides insight into Stahl and how his experiences researching similar subject matter for Pain Killers shook him so heavily: “There were two things that most affected my view of the world. One. One was the defeat of Spain. And the other… was Dachau. And Dauchau was minor compared to Auschwitz. It was an unbelievable horror. A thing so horrendous that you could not take it all in without becoming frenzied and hysterical and… and mad.”1

It’s obvious that Stahl and Kaufman are more fascinated by Gellhorn than they are by Hemingway while watching the film. Though Hemingway may not quite be the “overrated, ass-kissing narcissist” or “self-serving selfish bastard”1 that other characters in the film describe him as being, it’s clear that he wasn’t what drove Hemingway & Gellhorn’s writer or director.

Stahl stated shortly after the film’s release that “Martha Gellhorn was a bigger badass than Hemingway. She had more balls. She lied her way into covering the invasion of Normandy on D-Day and was actually there on the beach while the rest of the press corps was safely ensconced on a distant ship. Hemingway was with the other journalists on the government-sanctioned ship.”2 He later stated, “To me, Martha Gellhorn was the more interesting of the pair, so I made the choice to have her tell the story… She could laugh at herself in a way Hemingway never could.”3

Hemingway & Gellhorn premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, then went on to air on HBO in late May of the same year. Though the highly accomplished and expertly executed film unjustly received mixed reactions from audiences and critics, it went on to receive several awards and even more nominations from such organizations as the Writers Guild of America (the only nomination that Stahl and Turner would receive), the Golden Globes, the Directors Guild of America, the Screen Actors Guild, and the Primetime Emmy Awards (which nominated the film in several main categories—including actor, actress, and director–and awarded it two for its music and sound editing).

Right around the time of Hemingway & Gellhorn’s release, Stahl’s then-girlfriend and future third wife gave birth to his second daughter. Shortly after, Stahl would also face another life-changing event with the tragic passing of his mother.

The Pain Snob continues in part 6 of 7.

< 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources >