**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

Introduction

Absurdity and pain are not mutually exclusive. Not even close.

—Jerry Stahl, Permanent Midnight

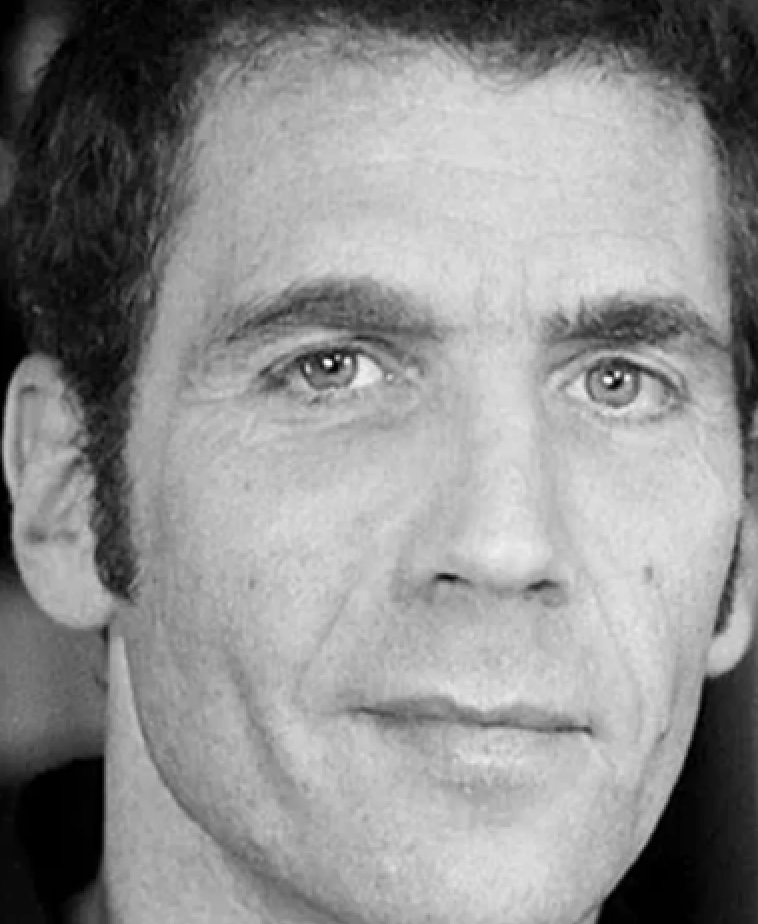

Jerry Stahl is probably best known as the junkie writer who created ALF. The fact that he had nothing to do with the ‘80s television series’ creation and that he is only credited for writing three episodes (which he admits to being high while doing so and having very little memory of) is about as well known to mainstream audiences and readers as anything he has written since. This excludes, of course, his first memoir, his fictionalized Fatty Arbuckle biography, and some Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay blockbuster starring Will Smith and Martin Lawrence.

Stahl’s Permanent Midnight, his first published book, is the ultimate true Hollywood/drug tell-all of its time. The 1995 memoir was successfully marketed as a yuppie horror story: a successful screenwriter behind beloved ‘80s sitcoms and television dramas leads a double life as a heroin addict and an all-American family man. The book is wickedly hilarious, self-effacingly candid, and heartbreakingly vulnerable–oftentimes, all at once. Blunt sarcasm and hyper-intelligent self-awareness replace any and all forms of self-pity. Stahl’s sardonic, depraved, and strangely (though always sincerely) heartfelt voice was subsequently born into the world.

Talk shows, magazine profiles and interviews, and a movie adaptation starring Ben Stiller all followed within a few years’ time of the book’s publication. A career was (re)born. Stahl’s name eventually started reappearing onscreen for titles like the original Crime Scene Investigation television series and the afore-alluded Bad Boys 2–far cries from his early ‘80s screenwriting endeavors in surrealist hard-core pornography.

Most important to him and his substantial cult of fans, however, he also continued writing books that only Jerry Stahl could write. Perv–A Love Story; Plainclothes Naked; I, Fatty; Love Without; Pain Killers; Bad Sex on Speed; Happy Mutant Baby Pills; OG Dad; and Nein, Nein, Nein! are the works, along with Permanent Midnight, that make Jerry Stahl the master of his own individual genre, though it is one that is very difficult to describe.

Stahl’s best and most personal works fit into a very specific niche that heavily appeals to addicts, depressives, borderlines, perverts, and all other forms of supremely damaged people. If Terry Southern, David Lynch, Jim Thompson, Lenny Bruce, William S. Burroughs, Todd Solondz, Hubert Selby Jr., and John Waters all pooled their collective genes into a mutant creation designed to be raised within the confines of the Neverland Ranch, it would grow up to write books just like Jerry Stahl’s.

Not exactly unsung, though not exactly widely celebrated, much of Stahl’s writing is, needless to say by now, not for everyone. In interviews, Stahl has referred to himself as a “pain snob,”1 someone who is unable to relate to anyone who hasn’t experienced life’s harsher realities through a hypersensitive perspective similar to his own. “I don’t trust people who haven’t suffered,”1 Stahl has admitted. Reactions to his work hold the same logic in reverse: those who can’t relate will most likely turn up their noses in disgust and walk away.

If this retrospective proves nothing else, it’s that this is probably the way it should be in today’s backward-moving world, anyway.

Growing Up Jerry (1953-1975)

Jerry Stahl was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on September 28, 1953. His father had emigrated to the States at ten years old when his mother eventually came back for him after leaving him in Lithuania with family members when he was two. Jerry’s father would often remind his children of his harsh upbringing, telling them that his family was the only one in his village who didn’t own a cow.

Jerry’s father went on to work his way up from nothing, starting as a coal miner, then becoming the Attorney General of Pennsylvania, then, eventually, becoming a judge on the Third Circuit. He was sweet-natured but emotionally distant and temperamental, as evidenced by the many holes in the walls of the Stahl household that were created by his smashing his head against them. Jerry would later say that the wall damage made his childhood home resemble a “museum of Dad rage.”1

Jerry’s mother was also smart and educated, as she held a degree in child psychology, but was emotionally and verbally abusive and often needed psychiatric care due to bouts of extreme depression where she did not leave her room for days. Jerry would theorize many years later that part of his mother’s issues stemmed from the fact that she was fiercely intelligent but unfulfilled and stifled by the oppressive times and by the life of a stay-at-home mother.

Jerry also has a sister who is six years older than him.

Aside from his troubled home life, some aspects of Jerry’s childhood in Pennsylvania were relatively normal. He played and followed sports when he was young, but never considered himself a jock, as he has since confessed that he never even learned how to ride a bicycle.

Increasingly feeling like an outsider as he grew, Jerry simply didn’t fit in with the primarily blue-collar surroundings where he and his family lived. The Stahls were the only Jews in their Italian/Polish/Irish Catholic neighborhood and Jerry was, in his words, “the only Jew in a grade school of 800. I used to get beat up for killing Jesus, which I must have done in a blackout because I couldn’t remember doing it.”2 Jerry’s Jewish heritage made him feel like an outcast, and his illiterate Polish grandfather would often remind him, “if you ever forget you’re a Jew, a Gentile will remind you.”1

As Jerry matured, he admittedly became more of a self-described “loner.”3 He was first introduced to drugs at fourteen when he took mescaline with his sister. Jerry also credits his sister for turning him onto music, specifically the work of Bob Dylan. Jerry went on to also listen to bands like The Rolling Stones and The Seeds around this time.

For high school, Jerry attended a private boarding school, The Hill School, outside Philadelphia, which is the same school Oliver Stone attended as a youth. Jerry felt out of place there, as well, as he didn’t particularly mesh with most of his classmates and their privileged, upper-class backgrounds.

Jerry’s already troubled world was shattered at the age of sixteen when he received word that his father had committed suicide, something that would, along with the actions of his mentally ill mother, go on to endlessly haunt him and his work. The summer after his father’s death, Jerry had to care for his mother at home and recalls having to carry around smelling salts because of her tendency to pass out at a moment’s notice.

Around this time, Jerry found solace in his newly discovered passion for reading and writing. Initially, he had wanted to be a standup comedian along the lines of his idol, Lenny Bruce, or to be in a rock band, but Jerry soon realized that that, in his words, “required talent and the ability to leave my room.”4 The first book that Jerry has recalled being grabbed by is Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, which was given to him as a gift by his sister’s then-boyfriend. Another life-changing moment was when Jerry read West’s The Dream Life of Balso Snell and was riveted to read the words “written while sniffing the forefinger of my left hand.”5

Another one of Jerry’s earliest literary influences was Flannery O’Connor. “I love novels that are disturbing in their humor, and truer about human nature than more somber efforts,”6 Jerry explained about his affection for O’Connor’s work. Writing was, in his words, where you could “say the things you wouldn’t necessarily say to someone’s face.”7 Teenage Jerry would be equally blown away by Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and went on to voraciously read the works of Charles Bukowski, Stanley Elkins, Ishmael Reed, Philip Roth, Vladimir Nabokov, Louis-Ferdinand Celine, Bruce Jay Friedman, Norman Mailer, John Barth, Hubert Selby Jr., and Terry Southern.

After graduating from The Hill School, Jerry attended Columbia College in New York. He dropped out shortly after and traveled to Europe and surrounding areas, working in London as a bartender at an Irish pub and briefly living in a cave in Matala, Crete. Stahl eventually returned to Columbia and graduated in an impressively short time period of just a year and a half. Socially, Stahl considered himself to be a “lonely weirdo”3 at the time and threw himself into his writing and his studies.

While at Columbia, Jerry discovered an interest in journalism and idolized such talents as Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe. For inspiration, he read Wolfe’s The New Journalism and Terry Southern’s Twirling at Ole Miss repeatedly.

Jerry’s first paid writing job was around this time, writing term papers for a company in San Francisco, which, in his words, “was more of a writing scam.”4 Shortly after, at only twenty years old, Jerry started writing for the Santa Cruz Times, a ‘70s alternative weekly publication. One of his most memorable pieces involved his review of a bisexual bar called Mona’s Gorilla Lounge.

Though he was highly productive during this time period, Jerry was still plagued by depression and his ever-increasing drug use, and even survived what he described as a “half-hearted”3 suicide attempt. He continued to work diligently, however, and went on to obtain his graduate degree from Goddard College in Vermont.

Early Career: Journalism, Short Stories, and Porn (1975-1985)

After receiving his graduate degree, Stahl worked as a journalist while living in New York City. He also wrote novels and short stories during this time period, and was sending out submissions to publishers that were consistently rejected. Over the years, he would go on to write six unpublished books before Permanent Midnight’s publication in 1995. Though some chapters and segments of these early books would later go on to be printed in magazines and/or short story collections, their entireties have since been forever lost. Though hard to see at the time, Stahl now considers his early failures as a “weird gift”1 that helped him not take his future success for granted.

Stahl found his first taste of success and validation for his creative work in 1976 when he won the Pushcart Prize for a short story that had previously been rejected by Hustler magazine. Eventually published by the now-defunct quarterly publication, Transatlantic Review, Stahl’s The Return of the General is about a young man whose penis becomes the reincarnation of George Washington.

This strange predicament leads the story’s now-desired narrator to wonder, “Did the ladies love me for myself, or were their thrills contingent upon the inspiring presence of The General?”2 Though conflicted, the narrator is eventually able to appreciate the situation, as he explains, “We’d had a good time together, George and I. He did the dirty work and I felt the explosions in balls and brain. Not bad. His was the labor that won nations, mine the profligacy that lived off that kind of sweat.”2

The story ends on an oddly positive, though equally absurd, note, with Washington giving his host priceless romantic advice: “My advice to you, Son of the Second Century, is find [a woman] you really like and stick to her. A good woman is hard to find.”2 The Return of the General, though difficult to track down today, serves as a highly telling beginning to Stahl’s wholly unique, personally revealing, and sharply hilarious brand of writing.

Despite working regularly as a journalist, Stahl still struggled to survive in New York City. For a time period, he slept under wooden seats in a dance studio. Later, he lived on the eighth story of a walk-up apartment building that had common bathrooms. Stahl’s drug use continued to increase in New York. “I was not a guy who used drugs to party,” Stahl has since explained, “I used drugs to work.”1

Stahl was a journalist for a number of publications early in his career. He did feature magazine writing and specialized in first-person immersion stories. Amongst other topics, he wrote about a nude singles retreat called Elysium, Ronald Regan’s brother, a bounty hunter, and mortuary conventions. He also found work in the porn business, a place where Stahl’s candidly raunchy voice could thrive without judgment or censorship.

The diverse group of publications that employed Stahl during his early years includes The Village Voice (which he first started while still in school and continued to write for while simultaneously writing porn), Beaver (which was his first porn-writing gig and for which he did a piece called Poon Tang With a Country Twang), NY Press, Club International, Juggs, Penthouse Forum (for which he wrote fake sex letters and answered them under the pseudonym of Ben Jarrod), Real World (for which he wrote a piece called Confessions of the World’s Greatest Sex Letter Writer), New York Magazine (for which he wrote a piece about a Puerto Rican little person who became a wrestler in the Bronx), Quarry West (for which he interviewed Marco Vassi), California (for which he wrote ten-thousand-word pieces), and Playgirl (for which he wrote the column, His Turn, under the pseudonym of John Andrews).

The next chapter of Stahl’s life began when he answered an ad in The Village Voice for Larry Flynt’s pornographic Hustler magazine. He was hired by the publication after he successfully wrote a descriptive ad for an electronic masturbation device. Stahl was initially thrilled to be working in such a sexy environment, but soon found himself to be disillusioned when he showed up for work and saw “a roomful of ladies who look like Aunt B. shoving dildos into boxes.”3

The Hustler job took Stahl to the then-location of Hustler’s headquarters in Columbus, OH in January of 1978. Stahl accepted the opportunity to relocate out of hopes to stay clean and quell his ever-increasing need for drugs, but that didn’t last long. During his brief stay in Columbus, he lived in the YMCA, then on the first floor of a house near OSU.

While at Hustler, Stahl wrote “girl copy”4 which were cheery descriptions of the magazine’s featured girls, and reviewed reader mail. He also wrote humor for the magazine, which introduced him to one of his most noteworthy future collaborators, Stephen Sayadian, who was, at the time, Hustler’s Creative Director of Humor.

Both Stahl and Sayadian relocated to Los Angeles in April of 1978 to continue working for Hustler. This was shortly after Flynt, who Stahl didn’t particularly care for, was shot and paralyzed. Stahl was shortly thereafter fired by Paul Krassner, who had taken over for Flynt, and was forced to go on unemployment.

Sayadian also left Hustler around this time and started his own company doing posters for films, including some by John Carpenter and Brian De Palma. Stahl and Sayadian continued to see each other socially, and their creative partnership grew from there. The pair had always wanted to make a movie, so they started shooting around ideas, and they eventually collaborated on a number of screenplays. A couple of their collaborations were eventually filmed, and these productions ultimately had an indelible impact on both men’s careers.

A former CEO of Hustler approached the now-successful Sayadian to make a porno movie for $30,000. Sayadian wrote the first draft for what would eventually become Nightdreams and Stahl, who Sayadian considered to be a “great collaborator,”5 rewrote it. Their intentions for the film, according to Sayadian, “were never designed to titillate,”5 as they wanted to “subvert the entire genre.”5

Since they both had goals to work outside of the porn industry, Stahl and Sayadian used pseudonyms. Sayadian’s work is credited as Rinse Dream. Stahl is credited as Herbert W. Day, which is the name of his old elementary school principal who used to paddle Stahl when he misbehaved. Stahl was proud to have exacted revenge on his former abusive authority figure by forever associating him with pornography.

Nightdreams’ production was done in true guerilla fashion. It was shot entirely on a soundstage on 35mm film and had a crew of only six people. Scenes were finalized, rewritten, or improvised right up until shooting began. The scene where Sayadian portrays a large piece of dancing and saxophone-playing toast, for example, was invented by Sayadian an hour before shooting.

Though cinematographer Francis Delia (using the pseudonym of F.X. Pope) is credited as the film’s director, it was essentially Sayadian who saw the movie through to completion, as he spent a good deal of time on its post-production.

Nightdreams combines pornography with sometimes-nightmarish, sometimes-playful, and sometimes-indescribable surrealism. It opens with a woman (Dorothy Le May) who is dressed in a hospital gown and hooked up to electrodes while two doctors (Jennifer West and Andy Nichols) observe her. The woman masturbates while delivering vividly descriptive dirty talk: “I know you’re watching me. I can feel your eyes like fingers touching me in certain places. I can feel my pussy so open you can see inside me. I feel so juicy. I can’t stop. I feel my clit so wet no one can see. I feel so dirty.”7

As they progressively increase Le May’s stimulation, the doctors try to get her to “learn to handle pleasure” because “her husband says she’s never had an orgasm.”7 The pornographic scenes intercut with the doctors and Le May represent her heightened and over-sexualized imagination as her brain is fed electric jolts. The more stimulation the doctors feed Le May, the wilder her fevered sex dreams become. These hard-core dreams feature, amongst other extreme perversions, a masked Jack-in-the-Box man who penetrates Le May with his elongated nose, cowgirls having a threesome in the desert, Le May being taken by a group of hookah-smoking Arabs, Le May masturbating a man and discovering a rubbery fetus where his penis should be, Le May performing oral sex on a man dressed as a Cream of Wheat box, a visit to a bondage-filled hell, and an oddly beautiful and tender encounter that takes place in a heaven-like setting.

In the observational setting segments, the increasingly aroused Le May delivers impassioned, insightful, and oddly feminist porno poetry monologues: “You think I’m a whore. You think I like to let strange men touch me—that I spread my legs in dark motels and watch in the mirror while they grab my pussy and stick another quarter in the tv. You think I’m cheap, but I don’t do it for money. I do it because I want to. You think I do it for you. That’s why you stare at me.”7

Nightdreams, though unrefined, is a bold experiment that, like most of Stahl’s most notable work, is impossible to categorize. Sayadian would discover a more finessed and concrete voice in future films that he would direct by himself. Nightdreams still showcases his potential, however, and the pure uniqueness of his still-developing voice. It is a strange, disturbing, and effectively dreamlike film that offers some truly unforgettable moments.

Despite everyone’s best efforts, Nightdreams’ financiers were unhappy with the final product, telling Sayadian, “You guys went too far.”5 The film was eventually a success, however, as it grossed over a million dollars through art house screenings after its release in 1981. Neither Sayadian nor Stahl owned a piece of the film, however, so they were unable to reap any of the rewards. Sayadian, at the time, was just happy to be making a movie.

It was around the time period of Nightdreams’ initial release that Stahl, then in his late twenties, became dependent on heroin. He still continued to throw himself into work, however, and his productivity remained impressive.

Stahl had an idea for a post-atomic movie before The Road Warrior made it to screens. This idea would eventually become the cult classic, Café Flesh. Stahl and Sayadian collaborated on the screenplay and Stahl stated that his and Sayadian’s goal was to “perpetrate a World War Three musical. We had in mind a kind of high-rad Cabaret in which trendy mutants and atomic mobsters held sway over survivors bombed beyond all normal pleasures. Lots of people made movies about the end of the world, but how many showed what the night life would be like?”6 Sayadian would be the only official director this time around, and his goal was to give the film a ‘50s-era pop feel.

The time period of the early ‘80s was the height of the porn era. It was then easier for Sayadian to find funding for a porno movie than it was for a so-called ‘legitimate’ one, but that didn’t stop him from initially trying to make Café Flesh, though intended for adults, as a non-porno. The challenging and uncommercial subject matter, however, did not make this easy. As Stahl explained, “for half a year, [Sayadian] and I made like duck-tailed pundits, foisting our forecast of postnuke greenbacks on sniffy producers who clearly couldn’t wait to pry us off their sling chairs and spray the room with Glade.”6

The owners of the former adult establishment, The Cave on Hollywood Boulevard, wound up financing Café Flesh for $100,000. The financiers’ terms, however, made certain that their core porn audience would get what they want. “All we had to do,” Stahl explained, “was work in some poochy, so the raincoat crowd wouldn’t give us a bad review.”6 Turning the film into a piece of erotica didn’t stop Stahl and Sayadian from making it something that was creatively rewarding for them, however. “To nurse our integrity,” Stahl stated, “we crammed in all the disturbo words and visuals we could.”6 The newly eroticized script “wasn’t exactly the stuff of Gilbert and Sullivan, [but] it wasn’t quite Debbie Does Decatur, either.”6

Café Flesh was shot over the course of ten days on the same small soundstage which Nightdreams had been filmed. Like Nightdreams, the production was a strictly guerilla one. Expenses for the film were often paid with large groups of quarters taken from The Cave’s peep show slots. Electricity was illegally patched in to power the equipment. Extras were recruited from blood banks and methadone clinics.

After filming was complete. the financiers felt there weren’t enough sex scenes in the film. Defiantly, Sayadian and Stahl decided to put in the “most repulsive, repugnant, alienating, essentially autobiographical sex scenes we could imagine.”8 When the film was finally finished, no one quite knew what to make of its challengingly individualistic, subversive, and provocative nature.

The world of Café Flesh is best described by its opening voice-over/title cards: “Able to exist, to sense… to feel everything—but pleasure. In a world destroyed, a mutant universe, survivors break down to those who can and those who can’t. 99% are Sex Negatives. Call them erotic casualties. They want to make love, but the mere touch of another makes them violently ill. The rest, the lucky one percent, are Sex Positives, those whose libidos escaped unscathed. After the Nuclear Kiss, the positives remain to love, to perform… And the others, well we Negatives can only watch… can only come… to… CAFÉ FLESH.”9

Hosted by a fast-talking showman named Max Melodramatic (played by Andy Nichols, who also portrayed one of the observing doctors in Nightdreams), the hard-core sex shows at Café Flesh are bizarre pieces of surrealism and satire that entice the hungry, impossible-to-satisfy Sex Negatives who comprise the audience (one of whom is portrayed by an early-in-his-career Richard Belzer). “Could anything be sweeter than desire in chains?”9 Max asks his frustrated audience early on. “The skull in the cage knows the real bars are behind the eyes,”9 he later says in one of his intermittent, wisdom-sprouting monologues.

On the particular night in which the film takes place, club patrons are thrilled by the announcement that the famed Sex Positive performer, Johnny Rico (Kevin James), will be making an appearance. Awakening something in the audience, Rico’s upcoming presence forces many of the Negatives in the club to question themselves and test their limits. Many of the patrons’ fates are locked, but one or two of them have a surprise waiting for them on the other side of their boundary-pushing.

The bizarre, avant-garde, and hard-core sex shows that take place on Café Flesh’s stage feature such oddities as a man dressed as a milk-delivering rat who takes a woman while three grown men dressed as babies rhythmically bang bones onto their high chair tables, a (literally) pencil-headed businessman who takes a woman on a desk while his nude secretary repeatedly asks if he wants her to type a memo, girl-on-girl action centering on a woman who wears American Flag-decorated underpants, and a group sex scene that is choreographed like an extravagant musical number and is accompanied by bodiless hands that snap their fingers in rhythmic unison.

While utterly warped, there is also a truly inspired and strangely beautiful artistry that is running through Café Flesh. It is an adult film that is truly unlike anything else—pornographic or not. Imagine Eraserhead with disturbingly absurdist hard-core sex and you might come marginally close to understanding what the film is. Café Flesh is something unprecedented that has no built-in audience or market. Love it or hate it, it’s a rare film that proudly and entirely stands on its own.

Café Flesh premiered in 1982. Stahl, who arrived late to the premiere, saw “at least six rows of Japanese businessmen [file] out to commit ritual bus boarding halfway through.”6 The film initially only lasted a week in theaters. Owners of the adult theater chain, Pussycat Theaters, relayed to Sayadian that Café Flesh was the only movie they’d ever screened where porn customers, who usually liked to remain anonymous, demanded a refund.

Producer Mike Misel eventually saw the film, liked it, and partnered with Sayadian to get it seen. Non-pornographic stills were sent to theaters and the film was eventually booked by Landmark Theaters roughly a year after it first premiered. Café Flesh became a hit with the arthouse crowd. It replaced Friday midnight screenings of John Waters’ cult classic, Pink Flamingos, at Landmark’s celebrated NuArt Theater. At one point. there were over thirty prints of Cafe Flesh in circulation. The film eventually went on to gross roughly two million dollars. Sayadian fought for the rights to his film this time around, and eventually gained ownership of the characters and story.

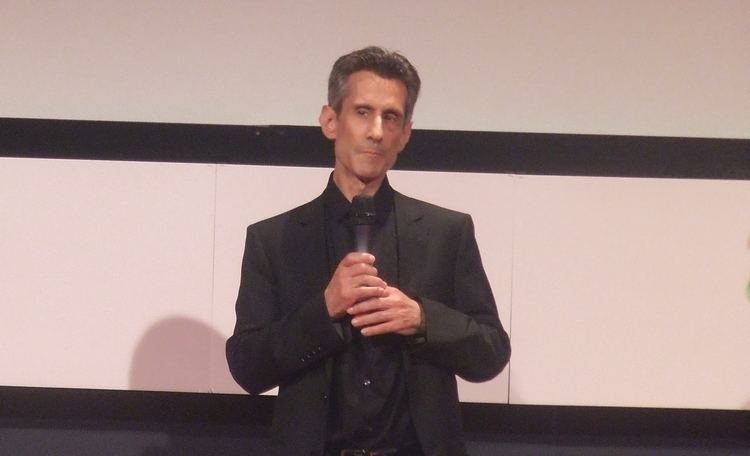

Even after finding notable success in the mainstream, Stahl still supports Café Flesh whenever he is presented with the opportunity to do so. He and Sayadian were both present at the film’s thirtieth-anniversary screening. There was also talk of Stahl and Sayadian remaking the film as a Broadway show or a cable series, though that has yet to happen.

Though being a cult porno sensation brought him other adult film offers, Stahl didn’t consider himself a “porno guy”6 and focused on his aspirations outside of the industry after Café Flesh. That being said, Stahl has never looked down on pornography, either. This is despite the fact that his experiences in the industry, in his words, “left me stamped with the sort of shady notoriety shared by spouses of mass murderers and Senate pages who tell all.”6 In fact, Stahl seems to take pride in his time in the adult entertainment world and has gone so far as to challenge popular thinking of the industry by describing it as, at the end of the day, just another business. Because so few people know someone who actually works in porn, Stahl states that “scads of citizens never realize that most of today’s thriving smutmeisters lead lives of no greater raciness than 20-year men from Mutual of Omaha.”6

Stahl and Sayadian had a number of movie offers after the success of Café Flesh. For reasons Stahl can’t remember, they instead decided to focus on a play they’d written together called Jackie Charge, which ran for six months in 1985 at the Gene Dynarski Theatre on Sunset Boulevard. The play was about a peeping tom “who becomes a hero, spawning peep cults all over the world.”10 The play was another cult success for the writing duo and garnered a number of noteworthy fans, LSD guru Timothy Leary chief amongst them. Stahl and Sayadian later wrote a film adaptation of the play, titled Rapid Eye Movement, but the manuscript has since been lost because, as Stahl put it, they “led disorganized lives.”11

It was a creatively adventurous time for Stahl that eventually resulted in great success (by Hollywood standards and not necessarily his own, that is). This success would make him an industry player–something countless people would kill to become. Stahl resisted it so heavily at the time, however, that it would ultimately play a large part in his downfall. Also, perhaps most notably, he would soon be able to afford more of the drugs upon which he was becoming so heavily dependent.

The Pain Snob continues in part 2 of 7.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources >