**Author’s Note: I would like to state upfront that this retrospective of Jerry Stahl’s life and career was done completely without his participation. I’m simply a massive fan of his and since there isn’t another complete chronological examination of his life and work, I figured I’d go ahead and fill that void as best as I could. This retrospective was written entirely with the aid of all the cited sources, and I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone, Jerry Stahl especially, for their work.

Beautiful Damage (2000-2001)

Shortly after Perv’s publication, Jerry Stahl discussed the premise for the next novel that he was working on, titled Fake White Light. The then-in-the-works book had the hilarious premise of a man who comes back from the dead and no one—not his wife or his family—is happy to see him. Though the description made it sound like another absurd and darkly humorous Jerry Stahl novel, it seems to have never been completed and was never published. The work on this aborted project didn’t seem to slow him down too much, however, since Stahl’s next novel would be published only a couple of years after Perv was released.

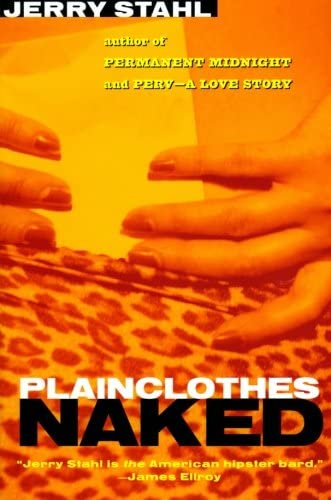

How Plainclothes Naked, published in the autumn of 2001, came about is not a particularly obvious story. Stahl claimed he was trying to come up with a new genre that he referred to as “crack noir” (a description used on the book’s cover), combining characters who heavily use drugs with film noir/crime elements.

The book also came from a much deeper and personal place, however, as Stahl explained, “I’d been out of touch with my mother for 10 years, then last year I got a call that she was being thrown out of a rest home because of her bad attitude. So my sister flew in from Nepal, and she and I met in Pittsburgh to move my mother. I was only in Pittsburgh for a day, but spending even a few hours with this person who‘d completely dominated my psyche as a child—and in many ways was still cackling in the back of my head—was like walking into a force field I’d spent my life trying to forget. Shortly after I first entered her room, she looked at me, reared back and parted her legs, and in that moment my entire childhood hit me like a fist in the stomach. All those sense memories triggered by the texture of her nightgown, and the wafting gusts of momness that flew out of her bed, took me right back there. I didn‘t know she still had that power, but it was as if the black hole of my past had been opened up again, and the night I left Pittsburgh I sat down and this book started pouring out of me.”1

Given the story relayed above, it’s no random occurrence that the book just happens to open with the following sentence: “Spongy buttocks exposed and wobbling, Tony Zank’s mother piled down the rest home corridor, screaming, ‘Help me!’ and ‘Stop the monster!’”2

Later, the reader is treated to even more details about this increasingly absurd and disturbing encounter: “His mother’s ankles felt like hot salamis as Tony Zank held her out the rest home window… He was surprised at how tough she was. And he wasn’t loving swinging her out the fourth floor of Seventh Heaven, where anyone could look up and see he wasn’t exactly running her a sitz bath. The worst part, though, was the view. Mrs. Zank wore nothing under her nightie, and every time Tony looked down he got an eyeful.”2

Plainclothes Naked, like much of Stahl’s work that came before and after it, so heavily mixes tones, genres, and styles that it is nearly impossible to categorize. Though it is an overall highly entertaining and effortlessly readable dark comedy, it wouldn’t be a Jerry Stahl book if it also didn’t contain powerfully truthful and wise observations of the human heart. Such observations are the cause of some truly beautiful and passionately romantic moments which counteract the book’s shockingly grotesque depictions of drug use, graphic violence, degenerate sex, and the general dark side of humanity.

Plainclothes Naked is, at heart, a highly intimate and achingly vulnerable look at love. This love, however, is a very specific kind of love that had and would find its way into just about every significant piece of Stahl’s writing: damaged love.

Set in Stahl’s childhood home state of Pennsylvania, Plainclothes Naked centers on Manny and Tina. The latter is a tough, seductive variation of a classic femme fatale/film noir antagonist. In Stahl’s hands, however, she’s a thoroughly developed character who rises above simplistic movie cliches and hides more painful and complex emotions through a well-practiced steely exterior.

Tina goes out of her way to appear as if she cares about and feels nothing. At one point, she offers some revelatory (for both the character and her creator) insight into her attitude, “This is how I do sadness. I get sarcastic.”2 Stahl takes great care in communicating the pain of Tina’s background to the reader, relaying her childhood sexual abuse (a common occurrence amongst Stahl’s characters) and the time she “found her mommy swinging from a noose made from pantyhose in their trailer’s living room”2 with heartbreaking and gut-wrenching detail.

That’s not to say that Tina is a complete victim without a dangerous side, however, as the first time the reader is introduced to her, she is trying to “decide between ground glass and Drano”2 to put into her Buddha-worshipping husband’s cereal bowl. When she ‘accidentally’ goes through with it, she is forced to explain the situation to the police, which is how she meets Manny.

Manny is a policeman who “hated the idea of being a policeman almost as much as he hated himself for being one… being a policeman gave him a reason to feel as badly about himself as he tended to feel, anyway.”2 Manny is a (kind of) former junkie who still privately chews codeine pills for relief.

When he meets Tina, there is an instant connection, as “Tina lit the tingle in the back of his head, the fuse that usually stayed damp, the one that got lit on those rare occasions when he met a woman who actually scared him. It was sort of like sex, but harder to find.”2 Manny will soon be “so in love that it hurt.”2 When Tina relays a story about her perverted grandfather eyeballing her privates as a child, Manny empathizes and tries to relate the only way he knows how: by relaying his own pain to let her know she’s not alone. “My mother made me cuddle nude till I was twelve,”2 Manny confesses, sounding like a passage straight out of Permanent Midnight or Perv.

Tina, on top of being questioned about her husband’s death, is also holding a secret. She works in the same nursing home that houses Mrs. Zank and has stolen a highly confidential photograph that Tina found under Mrs. Zank’s mattress. The 8 x 10 inch glossy features an image of George W. Bush with a tattoo of a happy face on his testicles with the inscription of “MISTER BIOBRAIN”2 written underneath.

This leads to two low-life criminals, the previously mentioned Zank and his partner McCardle, trying to track down and retrieve the photograph from Tina, which leads to Manny getting involved so he can protect his newfound object of infatuation. Endless instances of perversion, madness, and brutality ensue, making for an entertainingly demented and increasingly (though gleefully) shocking read.

When asked what character in the book he most identifies with, Stahl stated with some hesitation: “It’s dangerous to say ‘That character is me,’ but yes, I do identify with [Manny] probably more than the other characters in the book.”1 Though it’s not quite as present as it was in Permanent Midnight and Perv, the protagonist’s third-person internal monologue gives Manny a similar—sometimes almost identical—interior life as the first-person narrators of Stahl’s previous books. Manny, like many of Stahl’s other characters, is “A slave to empathy”2 who can sense and read pain almost telepathically.

The most telling instance of Manny’s inner thoughts manages to pretty much sum up the novel thematically while also providing some profound insight into the character and his creator’s psyche: “Maybe that’s what love was: damage loving damage, and in the process turning itself into something else, something—he heard the word in his mind and fought to keep from choking—something beautiful. Something—again his mind recoiled—something pure. Which felt like dying.”2

Though Manny is the obvious alter ego for Jerry Stahl in Plainclothes Naked, it’s important to note that most of his characters, like those of any genuine author, are variations of himself. A less flattering and less obvious alter ego is the character of Tony Zank, the raging, wall-plaster-smoking, skeevy crackhead who drops his abusive and mentally ill mother out of a four-story window in the book’s beginning chapters. Zank owns the same mother-supplied neuroses, anger, and pain that Stahl used for inspiration to start writing the novel in the first place. Perhaps Zank, in some form, is Stahl at his worst. Or, perhaps, he is who Stahl feels he could have become if he hadn’t gotten off drugs.

Plainclothes Naked is another underrated, profound, sensitive, twisted, and scaldingly funny Jerry Stahl novel. It playfully disturbs every bit as much as it enlightens, with the reader having to weed through many bits of extreme (and oftentimes hilarious) grotesqueness before hitting moments of vulnerable and inspiring tenderness. Its shock value and its sincerity go hand-in-hand, resulting in a (if you give into it) highly rewarding read that begets a plethora of beautifully conflicting emotions in its reader.

I, Jerry (2001-2004)

Around the time of Plainclothes Naked’s publication, Stahl worked for the first time with filmmaker Philip Kaufman (The Wanderers, The Right Stuff), someone with whom he would go on to closely work over the years and who would become something of a mentor and father figure to him. Kaufman, an avid reader, was an admirer of Stahl’s books and tracked him down with the intention of having Stahl adapt Jimmy Lerner’s memoir, You Got Nothing Coming: Notes of a Prison Fish, for the big screen. The book, about a former suburban Jewish family man whose life turns upside down after he is sent to prison for manslaughter, surely hit home with Stahl on a variety of levels. Unfortunately, the project never came to fruition.

Stahl’s first official screenwriting credit since the early ‘90s was earned when he wrote for the CBS series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, which centers on the employees of a Las Vegas crime lab trying to solve bizarre and brutal crimes.

How the mainstream job headed by producer Jerry Bruckheimer came about when the work that Stahl was best known for was a tad more fringe-oriented is rather straightforward. Stahl explained, “[CSI star and co-executive producer William Peterson] and I both go to the sort of Hollywood low-end YMCA, which is a very untrendy gym frequented by out-of-work, aging comedians and truck drivers. We were just sitting in the sauna, and we just started talking about books. It turned out he knew mine, and I knew his work. Billy said, ‘I’ve never done TV, but I have this one show I might do and would you be interested in writing for it?’ It was one of those fluky things where someone in Hollywood did what they said they were going to do—he got a show and he called.”1

The show turned out to be a truly wonderful fit for Stahl. Though it was a series with so-called good guys working on the right side of the law, it also went into heavy detail about the crimes perpetrated by so-called bad-guy offenders. With the series, Stahl’s tastes could flourish if he just stuck to the overall black-and-white, good guy vs. bad guy/degenerate formula that the show utilized. Stahl was able to take his affinity for all things perverse and shocking if he just used them in a less morally ambiguous/complex fashion that wasn’t the norm for all the characters in the series as they often were in his books. As long as the good guys were fighting against all things evil, kinky, or depraved, the audience was in a safe zone and Stahl could let his imagination run wild.

Stahl stated about the job, “What’s strange is that I get away with more quote-unquote transgressive weirdness on mainstream primetime network TV than just about anywhere else.”2 He also stated, “Usually, they hire you in spite of your voice. They know you’re this dark weirdo who writes about drugs and violence. They think that’s interesting, but they ask if you could do this instead. This time I got the gig because of my books, so there’s a lot of freedom in that. Now they want my voice instead of asking me to hide it and be Beaver Cleaver.”1

Stahl was credited for writing ten episodes of the series and also served as a consultant on many others. During his time writing for CSI, Stahl was even offered a full-time staff position, but turned it down to devote more time to his then-in-the-works next novel, I, Fatty. Given the fact that he was paid a mere fraction ($25,000) for the book that he would have made writing for the series, it’s clear that Stahl’s artistic passions were still what drove him above all else.

Stahl’s first-credited CSI episode aired in 2001 towards the end of the series’ first season and was titled Justice is Served. Its main storyline centers on a woman who trains her dogs to kill people so she can drink their blood and blend their organs into smoothies because it’s the only cure for a rare genetic disease that she carries called porphyria. The episode also features a storyline about a killer mother who drowns her daughter at a carnival and tries to make it look like an accident.

Slaves of Vegas aired later in 2001 during the early part of the series’ second season. It centers on a death that involves a dominatrix mansion run by a character named Lady Heather (Melinda Clarke). Lines like, “I find all deviant behavior fascinating in that to understand our nature, we have to understand our aberrations” and “It’s people who don’t come to places like [the dominatrix mansion] who I worry about—the ones who don’t have an outlet”3 sound like they come straight from Stahl’s novels. The episode also features a less-interesting subplot involving a robbery at a cash-checking store.

Felonious Monk aired in early 2002 towards the end of the series’ second season and features a primary storyline about Buddhist monks who are shot to death in their monastery near Vegas. It’s a pretty basic, though finely entertaining, episode that lacks any noteworthy perversion or strangeness (though pornography is, at one point, discovered at a Muslim temple). The episode also features a subplot involving a man who, years prior, supposedly killed one of the regular characters’ friends.

The Hunger Artist, which was the last episode of CSI’s second season, also aired in 2002 and features many lines and themes that belong in Stahl’s territory. The episode centers on the death of a well-known fashion model who suffered from body dysmorphic disorder and tried to fix her unhappiness with what was, essentially, self-mutilation. Many descriptions of the character sound like they could be describing a female protagonist in one of Stahl’s books, including “She was a screwed up kid lookin’ for a father figure… One day she’s bookin’ a photo shoot, the next minute she’s screaming for daddy.”4 The episode ends with a rather Stahl-esque observation: “The very nature of addiction—whether it be self-medicating or self-mutilating—is that the very behavior we use to survive it becomes the behavior that ends up killing us.”4 A character tellingly sums up the episode by stating, “All we are is what we try to get rid of.”4

Stahl’s next episode was for the early part of CSI’s fourth season and titled Fur and Loathing. The controversial episode sparked picket lines at CBS after it aired in the fall of 2003, as it primarily centers on the death investigation of a man found in a raccoon costume. This leads the series’ main characters to an encounter with “furries,” a subculture of people who have an active interest in animals with human qualities and, sometimes, even go so far as to dress up like them. The episode explores the kinky side of the phenomenon, going so far as to use and describe the terms “yiffing” (sex between two animal-dressed furries), and “furpile”5 (an orgy amongst animal-dressed furries). The episode also features a more-grounded and less-memorable subplot featuring the investigation of a man found dead and frozen to a walk-in freezer floor.

Stahl next wrote another episode for season four that aired in early 2004 and was titled, Getting Off. Stahl’s tastes are found throughout the episode, which contains guest characters who are pimps, prostitutes, addicts, transvestites. and clowns. The primary storyline centers on the death investigation of a wealthy addict and hepatitis sufferer (like Stahl himself was at the time) who is found stabbed to death in a bad part of town. This leads to the discovery of a dealer who pushes ibogaine, a hallucinogen that supposedly cures addiction, onto addicts. The secondary storyline of the episode starts with the discovery of a dead man in a junkyard who turns out to be a birthday party clown and ends with the perverse discovery of a housewife with a clown fetish and her jealous husband.

Stahl’s next-credited CSI episode is the milestone-reaching 100th episode of the series. Titled Ch-Ch-Changes, the episode was part of the series’ fifth season and aired in late 2004. It focuses on the murder of a transgender woman, which forces the main characters to take their investigation into the Las Vegas transgender community. Though the episode is not without its moments designed for shock value, it also displays an ahead-of-its-time empathy towards transgender issues, with a character stating, “Imagine being three years old, tormented by the sensation that you had the wrong parts. Your body’s like a foreign country and you’re stuck without a passport.”6

Stahl next wrote another episode for season five that aired in early 2005, titled King Baby. It was partially based on a piece Stahl wrote for Esquire UK. The episode starts with the murder of a powerful casino head, then takes the detective team into a strange subculture of grown men who like to wear diapers and be treated like overgrown infants. “Some guys,” a character theorizes, “can never love any woman but their mother. And some… never had a mother who loved them.”7 Another character astutely sums up the episode thematically by saying, “It’s only the truly powerful who have the power to relinquish power.”7

Stahl’s next CSI writing credit was for season six with an episode called Pirates of the Third Reich, which aired in early 2006. The episode begins with the discovery of a woman’s branded and mutilated corpse in the desert. The investigative team eventually learns that the woman was a victim of a modern Nazi impersonating his twin brother doctor. Something of a Josef Mengele (a Nazi doctor who would later turn up as a character in a future Stahl novel) wannabe, the man is conducting inhuman experiments on his victims just as the Nazis had previously done with concentration camp inmates.

The episode also features the return of the Lady Heather dominatrix character with her third appearance on the show. Lady Heather happens to be the mother of the woman who was discovered in the episode’s opening, and she proves to be an intelligent, strong, and justly vengeful character when she takes matters into her own hands to help solve the case.

Stahl’s last writing credit for CSI was for the final episode of its sixth season, which aired in 2006. Titled Way to Go, much of the episode focuses on a main character that is in a coma due to a gun injury in the previous episode. The other crime in the episode centers on a man with an hourglass figure/unusually small waistline who is found decapitated on a set of train tracks. This leads the investigative team into the world of Civil War re-enactments, which the victim took so seriously that he wore tight corsets that were responsible for his unnatural figure.

In the middle of his time writing for Crime Scene Investigation, Stahl also did work on and received a screenplay credit for what is, to date, the most-known film on his resume, Bad Boys 2, which was released in the summer of 2003. The film is a sequel to the 1995 Will Smith- and Martin Lawrence-starring action/comedy that was produced by Jerry Bruckheimer (whose production company, as mentioned earlier, was behind CSI) and directed by Michael Bay.

Bruckheimer, Bay, Smith, and Lawrence all returned for the sequel. An unabashed piece of popcorn entertainment solely designed to entertain and provide escapism, Bad Boys 2 isn’t exactly the ideal fit for Jerry Stahl’s voice or style. However, it does prove that Stahl is capable of writing outside of his own obsessions and comfort zone because there’s not much to it aside from his name that connects it to other pieces of his writing. The film is a Jerry Bruckheimer and Michael Bay movie, first and foremost, and Stahl was simply a (very handsomely paid) hired hand.

That’s not to say that Stahl didn’t appreciate the opportunity to work on Bad Boys 2. He was initially brought on board for a week-long rewrite of the film, but wound up staying on for sixteen weeks, then was let go right before production began. He earned more in four weeks of rewriting for the film than he did on all his previous books combined. Ultimately, the film paid for his house and his first daughter’s college education. Aside from the lucrativeness of it all, Stahl also thoroughly enjoyed the process of working with Smith and Lawrence and bringing their ideas to the screen.

It’s hard to say what, exactly, Stahl’s contributions were to the Bad Boys 2 script, as he claims that only snippets of his dialogue remain in the film. Like the majority of major Hollywood blockbusters, the Bad Boys 2 script passed through the hands of many writers before the film reached its final cut. Such major talents as Judd Apatow, Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg, Dick Clement, Brian Helgeland, John Lee Hancock, Brian Koppelman, Ian La Frenais, David Levien, Todd Robinson, and Marshall Todd all took a pass at writing the script.

The debate as to who would receive final credit went into arbitration, and the verdict wound up crediting only Stahl and Bull Durham/White Men Can’t Jump writer/director Ron Shelton for the writing of the screenplay. Marianne Wibberley, Cormac Wibberley, and Shelton were credited for the story.

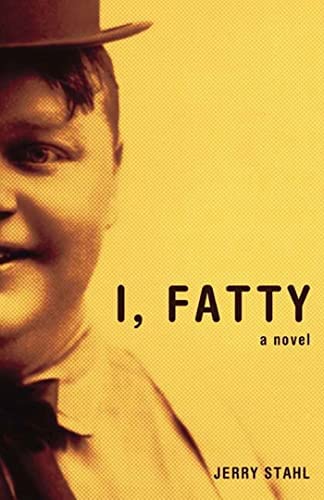

Also in the middle of his time writing for CSI, Stahl did extensive work on and saw the publication of his fourth book, a fictionalized account of the rise and fall of silent film comedy star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. The book went on to be Stahl’s most celebrated and renowned book since Permanent Midnight, and it brought him a whole new legion and class of fans. The work would not only appeal to Stahl’s very specific niche audience, but it would also be a major attraction for mainstream readers and publications, as well.

Published in the summer of 2004, I, Fatty was, at the time of its release, Stahl’s most ambitious novel. It combines mountains of Hollywood history with a risky and whole-hearted depiction of Arbuckle’s pained-yet-oftentimes-humorous internal voice (a wholly present and priceless aspect to pretty much all of Stahl’s literary protagonists). Stahl’s research on the book would be so in-depth and consuming that he hired David Berman, a Hollywood tour bus driver and, coincidentally, an actor who appeared regularly on CSI as a coroner, to help with some of the more arcane research details.

The book details Arbuckle’s impoverished beginnings, then goes on to focus on his relationship with his physically and emotionally abusive father who blames him, due to his mammoth size at birth, for his mother’s ill health and eventual death. The book next moves on to Arbuckle’s success, first as a live-show vaudeville performer, then as a star in one-reel shorts for Keystone Studios, then as a star and director of feature-length Hollywood comedies for Paramount. It also focuses on his relationship with friend and collaborator Buster Keaton and on his pained-yet-loving relationship with his well-meaning and eternally supportive first wife, Minta. Most painfully, the book offers an uncompromised depiction of Arbuckle’s downfall into heroin addiction, alcoholism, and, eventually, despair after being accused of the manslaughter and rape of model and actress Virginia Rappe.

The book originally started as something different than its final product, as Stahl explained, “The book’s origin is a little peculiar. Originally, I was asked by Bloomsbury to write a little nonfiction book for a series they were doing, to be edited by Joel Rose, who has a really great and original novel called Kill the Poor. Anthony Bourdain, who got Bloomsbury to hire me, wrote a fantastic thing for the series, about Typhoid Mary. But I couldn’t get mine off the ground. Every time I started, it sounded like a fucking term paper. Either that or I’d go all hagiographic on Arbuckle’s ass. So finally I just went off the reservation and did it as fiction, the way I heard it in my head, as this kind of sad, funny fat man’s cri de coeur. Bloomsbury was gracious enough not to sue for breach of contract and actually published the book.”8

Stahl loved writing about Hollywood’s early years and was obsessed with William Randolph Hearst’s invention of the tabloids. Though he wasn’t previously interested in Arbuckle’s films and it took some time for him to discover Arbuckle’s voice, Stahl stated that he fell in love with him and connected with his abandonment and pain after he saw a sad-looking photograph of Arbuckle wearing pants and a derby hat that Charlie Chaplin had given to him.

Stahl vehemently believes in Arbuckle’s innocence of the crime against Rappe, a stance that is firmly taken in his book. He took on this belief after research revealed to him that Rappe had given the clap to half of the actors who portrayed Keystone Cops in Mack Sennett-produced comedies. Stahl’s belief was further supported by the discovery of the fact that Rappe had an abortion the day before her alleged encounter with Arbuckle, something which contributed to her death from peritonitis.

Further supporting his opinion that the entire situation was nightmarishly unfair to Arbuckle, Stahl also discovered that the then-head of Paramount wrote a check to the District Attorney in one of three total Arbuckle trials (the first two of which had a hung jury and the last of which found him innocent) to quickly and discreetly put Arbuckle away without drawing any negative publicity for the studio.

His most classically structured and narratively straightforward novel to date, I, Fatty mostly drops the shock value-driven and playfully sarcastic tone of Stahl’s previous books, allowing room for clear, sympathetic, and painfully unfiltered emotions and insights. Stahl exhibits the same naked vulnerability and honesty he had achieved in his previous books with I, Fatty– only now, instead of buffering the more painful truths with dark humor, he conflates his own experiences and voice with those of a historical figure.

Stahl captures Arbuckle’s voice so effectively by personalizing it and making it his own while also adjusting his own style and tastes. While it’s overly simplistic to say that Stahl is wholly writing about himself in disguise with I, Fatty, it’s equally as simple to say that he didn’t put an immeasurable amount of himself into it, as well.

Stahl once addressed the question of how personal and autobiographical I, Fatty is to him when he stated, “The late [actor] Philip Seymour Hoffman, who was originally slated to play Roscoe Arbuckle [in a movie adaptation], told me the first time we met that he thought the book was actually more about me than about Arbuckle. He saw it as a kind of disguised autobiography—me in a fat suit, which Fatty actually had to wear after he lost a ton of weight kicking a heroin habit.”8 Given Stahl’s instinctual writing process, it’s likely that he wasn’t fully aware of his voice being so present in the final draft of the book until it was brought to his attention after its completion.

Stahl further elaborated, “The emotions—if not, obviously, the action—are inescapably autobiographical; pain, at least in my view of the world, has a kind of universality to it. A hammer to the ankle hurts the same way whether you’re the president or a petty thief. With this in mind, I could somehow graft the dimensions of my particular psycho-depresso—but occasionally ecstatic—history onto the life of some portly bastard who grew up in a dirt shack and died having owned a car with a toilet in it… And I remember talking it out loud and taking it down, not exactly like dictation, more like I wanted to remember what came out of my mouth so I’d know what to tell the doctor. People have lofty words like channeling, or being a vessel. Which, god bless, I am thrilled to hear is their experience. With me it’s more like I had Fatty Tourette’s. It was like being a ventriloquist with no hands.”8

Those familiar with Stahl’s life and works can easily spot the threads that connect I, Fatty to his previous books and publicly relayed life experiences. If you were to place Jerry Stahl into the silent film era as an overweight comedic star, give him an absent mother figure instead of an absent father figure, then replace his abusive mother with a drunken and abusive father who forever torments his psyche, he would probably write an autobiography that is quite similar in tone, personality, and style to I, Fatty.

In the book, Arbuckle sounds a lot like Stahl talking about the relief of his past drug use after Arbuckle thinks about his father’s many abusive and emasculating remarks and states, “I had to pinch my own thigh through my pocket until tears came, to create an outside pain big enough to blank out the pain inside, the pain in my fat boy’s heart.”9 When Arbuckle states, “This being my story, bad always leads to good–before it leads to more bad,”9 it might as well be a line from Permanent Midnight. When Arbuckle wonders, “Why would anyone who survived my family want to even think about starting another one? How many prisoners of war reenlist?”, it reads like an outtake from just about any Stahl book or interview. It could easily be Stahl talking about himself with his darkly dry wit when Arbuckle states, “I can’t get sent to hell, I already get my mail there.”9 The Arbuckle/Stahl voice is further blurred by such bluntly revelatory and familiar lines as, “sometimes pain is the one thing left a man can feel.”9

Arbuckle, at times, even holds the same disdain for Hollywood that Stahl once held early in his screenwriting career: “Moving pictures, as far as I could tell, were made by hacks and peddled to idiots.”9 Stahl and Arbuckle also suffer the same pain of being known for something that humiliates them: Arbuckle hates being called “Fatty” just like Stahl hates being known as the junkie who used to write for ALF. “I guess that’s success,” Arbuckle at one point theorizes in the book, “getting paid for the same thing that used to make you wish you were dead.”9

I, Fatty doesn’t claim to strictly depict what happened in the past. It is not a piece of history, it’s a work of art that interprets and filters history through the vision of its creator. The book is as engaging and easily readable as it is because, first and foremost, its author put so much of himself into it that anyone, with even the slightest amount of empathy, can identify with it on a very basic human level. I, Fatty is, quite simply, a monumentally impressive achievement because it shines a very telling light on the past while providing endlessly fascinating and painfully personal insight into the human condition.

Moreso than Stahl’s previous two novels, I, Fatty was both a mainstream and critical success, debuting at number nine on the New York Times’ bestseller list. Johnny Depp’s production company, Infinitum Nihil, purchased the film rights to the book in perpetuity with the intention of Depp playing Buster Keaton. Depp’s The Libertine director, Laurence Dunmore, was, at one point, attached to direct. As stated previously, Philip Seymour Hoffman was set to play Arbuckle, but the actor’s untimely passing prevented it. The film adaptation is, to date, yet to become a reality.

The Pain Snob continues in part 5 of 7.

< 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sources >