Part Four: The Smell of Rain Brings Forth Fulfillment

For his next screenplay, Burnett returned to the core of an idea that was present in both Red Meat and his first unpublished novel, Orwell’s Year: a self-centered man who selflessly falls in love with a terminally ill young woman. This time around, Burnett altered his story to fit the characters of an aging, wealthy playboy and a precocious nineteen-year-old woman with a heart condition.

Originally titled May December, the script was the talk of Hollywood when it sold in the late winter of 1997 to Lindsay Doran at United Artists. For the next two years, it garnered Burnett countless meetings, free lunches, and endless praise. It became his calling card.

Doran was passionate about the script as written, and made a personal promise to Burnett that she would do everything in her power to protect it. Burnett, perhaps for just a moment, was relieved and reinvigorated by the prospect of a commercial and artistic hit.

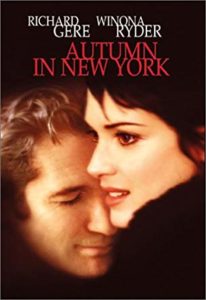

May December almost went into production in the fall of 1998 with the title change of Autumn in New York, but that deal quickly fell apart when Richard Gere backed out at the last minute. George Clooney and Drew Barrymore were next in line to take over the leads, but the studio decided to give their first choices one last try.

Lindsay Doran remained true to her word as long as she could. Sadly, she was fired in the spring of 1999, leaving Burnett’s treasured screenplay vulnerable, as during a studio shake-up, the first thing to go is almost always the previous administration’s favorite projects. Burnett, however, got lucky:

“Chris McGurk the new chief operating officer of MGM was sitting by the pool one day, reading through the pile of scripts the studio owned, deciding which were to get the ax, when his wife Jamie picked up a script and said, “I went to high school with this guy.” She read Autumn in New York, cried, and told her husband he should make the movie.”

Autumn in New York (2000)

Like Bleeding Hearts, the producers of Burnett’s screenplay chose a relatively inexperienced director in actress Joan Chen. Unlike Gregory Hines, however, Chen was coming off of a beautifully executed directorial debut– the Chinese film, Xiu Xiu: The Sent-Down Girl. This still wasn’t enough to prepare Chen for what was to come.

Richard Gere eventually accepted the lead role of Will Keane. Winona Ryder was cast as Gere’s younger love interest, Charlotte. Possibly threatened by her screen presence and star power at the time, Burnett believes that Gere took an almost-immediate disliking to Ryder. He subsequently had Burnett fired and hired Oscar-winning screenwriter/Tony-winning playwright John Patrick Shanley to do a last-minute rewrite only five days prior to shooting. “Allison is Winona’s writer,” Gere reportedly explained. “I need my own writer.”

Gere disliked most of Shanley’s rush job, but, nevertheless, two days before shooting he had chunks of Shanley’s dialogue dropped into every scene in which, Burnett states, “Gere felt Ryder’s character had the upper hand.”

“Why do you want to talk so much?” Joan Chen would reportedly plead. “It’s not sexy.”

Gere and Shanley minimized Ryder’s role to be little more than an effervescent porcelain doll. She was now present to make Gere’s character stand out and shine while having little interior life, desires or motivations of her own.

Much to Burnett’s horror, the height of Shanley’s damage to the script peaked when Charlotte wistfully murmurs to Will: “I can smell the rain. When did I learn how to do that?” Burnett still laments today: “The critics groaned and, of course, blamed the sappy line on the only writer whose name is listed in the credits.”

Gere reportedly refused to take direction from Chen on the set, which didn’t help his already strained working relationship with Ryder. While the talented actress did her best with what she had, her performance comes across as overcompensating for Gere’s obvious lack of interest. Their chemistry is forced and, at times, downright weird, often resembling more of an over-zealous teenager trying to rouse interest in a stoned parent than a passionate May-December romance.

Burnett summarizes his disappointment to this day: “Autumn in New York hurt the most because it was the first time I had seen something I wrote so cavalierly wrecked.”

Perhaps predicting a negative reaction, United Artists chose not to pre-screen the film for critics prior to the film’s release on August 11, 2000. The prediction proved correct, as critics were anything but kind in their reactions to the film. Empire’s Caroline Westbrook’s one-out-of-five-stars review called the script “self-important” and bluntly stated, “by the halfway mark, you’ll be desperate for Ryder to end her misery and yours.” Emanuel Levy’s Variety review was slightly kinder in stating upfront, “Autumn in New York is not a bad picture, just utterly banal.”

The film also failed to amaze at the box office. Earning just over half of its reported $65 million budget in the states, it managed to turn a small but unimpressive profit combined with foreign markets– where it did very well.

Burnett theorizes as to why: “Audiences are less judgmental about older men wooing younger women overseas. Also, they don’t speak English, a decided advantage when you run into Shanley gems.”

Putting the obvious criticisms aside, however, there is a quality and an essence that somehow pervades Autumn In New York. While it’s nowhere near the quality of its original screenplay (which this writer has read), it is still a film that’s very near to Burnett’s heart:

“There is much I love about Autumn in New York. I think very few movies have ever photographed NYC so beautifully. There is some good acting… some effective scenes. And it has a giant heart.”

Burnett V Gere

On the subject of Richard Gere, Allison Burnett has never and seemingly will never mince his words. He stated recently:

“I think Gere wants to be the adored, the beloved. He is a supreme narcissist. He hated Pretty Woman because he was forced to play the male lead. I think his unwillingness to play genuine leading men really hurt his career. I think he could have been great in Autumn, but he needed to leave the damned script alone and let himself be directed. Winona was adorable and so open to him. If he had shown her the simplest kindness, chemistry could have developed. Instead, he competed with her. And it deeply damaged the film.”

The Monday after the film opened second at the box office, Burnett sent an off-the-record letter to five on-line critics, explaining to them how the movie had gone so wrong.

Two small samples will give you an idea:

“The reality is this: the reason most studio movies are awful is not because the writers are stupid and the producers tasteless: it’s because movie stars are in control of the scripts. The tail wags the dog. Almost all the time. Or perhaps more to the point: the lunatics have the keys to the asylum.

When the London Times pushed me for commentary on Richard Gere and the rumors of what an asshole he is, I gave them only one quote: ‘I shudder for the future of Buddhism in America.’ “

Upon receiving Burnett’s letter, one of the critics, Susan Granger, asked if she could show it to some friends. Since he had already clearly told her that it was off the record, Burnett assumed that she meant she would show it to friends informally, face to face. Instead, she gave or sold the letter to the New York Post, who ran it in its entirety a couple of days later, filling all of Page Six.

In a follow-up article also published by Page Six, Gere defended himself by saying:

“People say it sounds like I killed his family and buried them in the backyard. But I didn’t read it so I can’t say … I can’t comment on it with any authority… I didn’t touch the character at all. I’m not the director. I’m not the producer. I’m not the studio. So where did I get that kind of…? — but again, I didn’t read the article. All I can say is that [Burnett] hasn’t called me.”

Although Burnett’s reps were worried, Burnett was quietly glad that the truth behind his butchered work was now available for public scrutiny. Burnett now states:

“I felt liberated. I had struck a blow for writers everywhere. I wanted it on the record what Gere had done. Usually stars destroy scripts with total power but zero accountability. Now he was outed. I wrote the letter because I was choking on the injustice of critics blaming me for terrible lines/moments I did not write.”

The Birth of B.K.

After the debacle of Autumn in New York, Burnett was in creative limbo. Craving more control over his work, Burnett decided to return to his dreams of becoming a novelist.

Now in his early-forties and with years of distance and maturity behind its initial incarnations, Burnett returned, once again, to his first attempt at writing a novel. Originally called What Frances Saw, and later retitled Orwell’s Year, the book had “lain in a drawer on old floppy disks for almost fifteen years since its early rejections.”

Orwell’s Year was twelve chapters, each of which represented a month of the year 1984, and each of which was told through a different point of view, sometimes in the third person and sometimes in the first. The book was an array of autobiographical tales of young and struggling artists, battling personal demons, striving for purpose, and embarking on dangerous sexcapades. Burnett describes it as “a giant, Joycean, kaleidoscopic experiment with almost no commercial appeal.”

While some of the book’s content had already been culled for Red Meat, Burnett’s passion for it fully returned upon the realization that it needed to be told from a new perspective. This sparked the creation of a singular narrator, one of his most personal and heartfelt characters.

B.K. Troop is a huge-hearted, middle-aged, sophisticated, witty, erudite homosexual New Yorker who suffers from rapidly cycling moods and acute alcoholism and survives off government-issued disability checks.

After six months of rewriting that began in the fall of 2000, Orwell’s Year became Christopher.

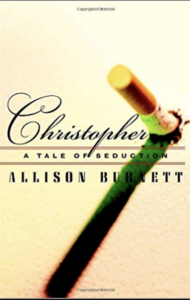

Christopher (2003)

Christopher was originally a character who weaved in and out of the chapters of Orwell’s Year. In Burnett’s updated overhaul, the story begins when Christopher moves into a New York brownstone apartment three doors down the hall from Mr. Troop in January of 1984. After their first awkward hallway encounter, the middle-aged B.K. is overtaken by the young man with “a smile so pearly white that I, as one deprived of dental care until the age of fourteen, could only marvel at.”

B.K’s personal mission and obsession in life becomes seducing Christopher, and soon deploys numerous, often comically haphazard, methods of inserting himself into his life. The more uninterested Christopher seems, the more obsessed B.K. becomes: “Soon, I would have the boy. Or, not to put too fine a point on it, he would have me.”

What could easily read as disturbing, almost stalker-like, behavior comes across as strangely endearing when it’s told through the eyes of B.K. Troop. Partially because he’s so neurotically lovable, but mainly because, as the story progresses, it becomes clear that B.K.’s enormous heart overrides his initial predatory intentions. It will “reveal itself in the fullness of time” just why Christopher entrances him as he does.

The heart of Christopher is B.K’s heart. In Christopher, he sees a young artist in need of guidance but, more importantly, he sees a young man who is suffering from pains which mirror his own. Like all of Burnett’s work when at its best, Christopher slowly and carefully reveals itself to be far more complex than it initially appears. What starts off as a darkly comical yarn turns into a moving examination of friendship between two deeply damaged but well-intentioned men.

B.K. becomes Christopher’s mentor as the young man deals with his chronic chastity, his toxic relationship with his narcissistic psychoanalyst mother, his precarious mental health, his nightmarish descents into the Gary Hart campaign/New Age cult, his writing, and, quite hilariously, his chain-smoking.

With his usual poetic grace, B.K. recalls the moment he let his heart prevail in the epic battle against his loins:

“Christopher was no longer a prey to be captured or a romantic idol at whose feet to fall, but a friend. Perhaps the first male friend of my life. I knew then that if our bond was to deepen, it would be solely on the spiritual plane, and I was content with that. In fact, I was grateful. Good God, what sort of love was this?”

Also keeping in tune with Burnett’s most personal works, Christopher goes beyond its in-depth character exploration by cleverly playing with its own narrative. A meta-awareness of the material becomes present towards the book’s end, and Christopher is ultimately revealed to be as much about the act of writing as it is about its characters. As is the case with most of Burnett’s work, the specifics to this are best left for readers to discover for themselves.

In B.K. Troop, Burnett created a voice through which he could bring to life his most personal material. He was also able to revisit the twenty-six-year-old who created it in an entirely new light. Burnett expressed what he had always wanted, but, with the distance of time, had been able to do so more accessibly.

The experience of seeing his work through, then gaining the interest of a publisher, was one of the most joyous he can recall:

“When I wrote Christopher, my agency William Morris gave it to Virginia Barber, a legendary agent in their NYC office. She read it over Fourth of July weekend and when she called and told me that she loved it, I almost fainted with joy. I had stored painful memories of the countless rejections of my twenties. Publishing a novel had been a long-held dream.

When a mere few weeks later, as I was driving off the Warner Brothers lot after a meeting, Ginger called to tell me that she had sold it to Broadway Books at Random House, I was over the moon. More exciting than any movie news I had ever received. Some of this is because of how much higher in esteem I hold the book world, but also because even the best news in the film world is tempered by the knowledge that at any moment you can be fired, your script pillaged, or the whole production shut down. With a book, good news is good news. If they buy it, they are publishing it.”

An Exciting, New Gay Voice

Although Christopher had been sold in the summer of 2001, it took nearly two years for the book to be released, as it was finally published in April of 2003. Broadway Books targeted gay audiences for Christopher, which soon lead to confusion as to whether or not Burnett, himself, was straight or gay.

Burnett’s editor was under the impression that he was working with an important, new gay writer from the get-go. Burnett was advised by his agency not to correct him. For the better part of a year, Burnett “hid in the straight closet” and let audiences invent their own image of him in their minds. He didn’t exactly tell people he was gay, but he didn’t do anything to stop them from thinking it either. But eventually his editor grew suspicious when Burnett shared his love of the Cleveland Indians and admitted that he had never watched a single episode of The Golden Girls.

The book sold relatively well (10,000 copies) and garnered rave reviews from The Sunday L.A. Times, The Advocate, The Chicago Free Press, and Instinct. It was also one of five finalists for the coveted PEN USA Literary Award in Fiction. While the experience didn’t make him rich or particularly advance his career, the publication of Christopher was a seminal moment in his creative life.

Burnett had once been a successful Hollywood screenwriter who was paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for his work. He’d driven a Jaguar, dined at the finest restaurants, and was even briefly engaged to Naomi Watts.

Now, he was a marginalized faux-gay author with a new and exciting voice. He had been paid pennies for work he was proud of and had to pound the pavement to get people to read it.

But he had never been happier in his life.

Our piece on Allison Burnett will continue in Part 5 of 9, which will focus on his next produced screenplays, particularly Resurrecting the Champ, and the publication of his second novel, also featuring B.K. Troop.