Part Three: Devoured by Red Meat

After the disappointment of Bleeding Hearts and since he could now “afford to draw a line in the sand” with the sale of his Freckles screenplay, Allison Burnett was ready to face the next challenge that so many screenwriters long for: directing.

In writing the screenplay for what would become his directorial debut, Burnett “reimagined and repurposed” scenes from his first unpublished novel, Orwell’s Year, which he had written ten years before, while living in New York City. The script, titled Red Meat, was dark and deeply personal. Burnett “harbored only the vaguest hopes of directing it.”

Almost immediately after its completion, a small production company offered to buy the script for David Burton Morris to direct. Morris’s film, Patti Rocks, had been a huge influence on Burnett in the writing of Red Meat. Another production team, however, was also interested and already had the financing in place. They also gave Burnett the added incentive of letting him direct the film himself.

It was an easy choice

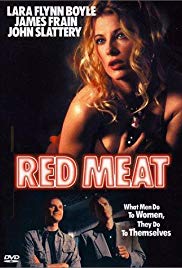

Red Meat (1997)

Allison Burnett’s screenplay for Red Meat is a challenging, politically incorrect piece of writing that unflinchingly and realistically tackles the subject of misogyny. The premise is simple: three men sit at a diner eating red meat, musing about their relationships and sexual escapades with women.

Stefan is the alpha male. Chris is the spineless beta. They both tell highly entertaining, hilariously ignorant, pathetically sexist, and dubiously honest stories about their sexual escapades. Victor is the loner who reluctantly joins the dinner after running into Chris, a former friend, by chance. Victor may be the most enlightened of the three, or he may just be the best one at hiding his barbarity.

Red Meat, like many of Burnett’s screenplays, attracted the interest of some top talent. The controversial nature of the film, however, proved to be too risky for any major star’s interest to progress past the flirtation stage. Vincent Gallo came the closest to committing, having expressed interest in the role of the mysterious Victor. He refused to audition, however, forcing the production team to look elsewhere.

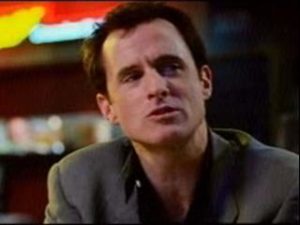

The final cast list featured no big names of its time, only two well-known actresses slightly past the height of their fame, Jennifer Grey (Dirty Dancing) and Lara Flynn Boyle (Twin Peaks). Some extraordinarily talented (though unknown at the time) actors rounded out the ensemble. Most notable among them were future Madmen star John Slattery as Stefan, and English character actor James Frain (Star Trek: Discovery and Tron: Legacy) as Victor. Chris was played by Stephen Mailer, son of Norman.

Production on Red Meat began in February of 1996 in Los Angeles. With a $500,000 budget and eighteen-day shooting schedule, the production was by no means an extravagant one. The experience proved to be an enlightening and rewarding one for Burnett, nonetheless. He credits cinematographer Charlie Lieberman (best known for his work on Henry: Portrait of a Serial Kiler) for teaching him the basics on lighting and lens choices. He also had a terrific relationship with his actors, particularly Slattery, Frain, and Grey, all of whom he praises personally and professionally. Grey, in particular, receives credit from Burnett for being the most experienced on set, and for keeping the mood grounded, light, and professional.

In spite of a few minor squabbles with the producers over a music cue here or a close-up there, Burnett was able, at long last, to see one of his scripts put onto the screen exactly as he had intended. The problem was getting a distributor. The film was dark and disturbing and had no male stars. Sundance Film Festival rejected it, but strangely accepted and embraced Neil Labute’s overtly misogynistic comedy, In The Company of Men, that same year.

Of Meat and Men

Red Meat was heavily overshadowed by In the Company of Men’s indie success, as it featured similar subject matter and themes. What made Men succeed was that it simplified the subject matter of misogyny and turned it into something shocking and inhuman.

Men strangely plays it safer, in spite of being so cruel, by creating a comfortable distance between its emotional violence and its audience with heightened, dark humor. The lead character (portrayed by Aaron Eckhart), who tricks a deaf woman into falling in love with him for laughs and other hidden agendas, is so unquestionably (and comically) evil that the audience will never have the uncomfortable moment of catching a glimpse of themselves in his eyes.

The female lead in Men is a lovable and hapless victim to two cruel men. In Red Meat, Burnett states:

“The women are complicit in their own abuse. It’s a film without heroes or victims. In my eyes, it’s a brutally honest film, about the way the war between men and women actually plays out in the real world.”

While Men was easily the more shocking of the two films, Red Meat was the more disturbing because of its subtlety. It never tells you whom you’re supposed to like or dislike, celebrate or vilify, believe or not believe

Red Meat wants its audience to enjoy the banter and tension among Stefan, Chris, and Victor. Then, the second we think we have them pegged, the second we’re comfortable with and entertained by their sensationalized machismo, the film methodically turns those expectations against us.

One of the film’s key sequences involves Stefan describing a comedy of errors in which he cheats on his live-in fiancé, Candice (Grey), then has to cunningly conceal the evidence from her.

Slattery’s effortless charisma easily sucks you into the thrill of his duplicity. Along with this, Burnett’s direction cleverly manipulates the viewer into thinking they’re in a safe, comfortable zone where it’s okay to enjoy the comically dickish character and, perhaps, even like him and laugh along with him.

Then reality enters. A confrontation escalates into Stefan slapping Candice hard across the face, and the audience, too, feels the bombshell aftermath of Stefan’s actions. In short, we’re smacked in the face right along with Candace.

Next, Jennifer Grey effortlessly carries out the film’s most important tonal shift, when, crying from the slap, she begs, “What did I do? What did I do?” Slattery’s face shows all the guilt and self-hate of a man forced to confront his own buried rage toward women.

Grey’s performance is heartbreaking, vulnerable, and resonates with a necessary and slyly calculated (by Burnett) tidal wave of guilt for anyone who thought Stefan’s tales were harmless male banter.

Barely thirty minutes into Red Meat we discover that the film was never about enjoying the lifestyle. It’s about the process of becoming and avoiding becoming “just one more arrogant white man who only knows lying and screwing and hatred.”

Another Burnett Epiphany

Allison Burnett’s work, at its best, only comes together as a comprehensible whole in its final moments. The audience is left with more information than it expected, but it’s information that could beautifully and frustratingly lead you in many different directions.

This Burnett Epiphany, as it was termed in part one of this piece, is the essential piece of his story, when everything simultaneously comes together and falls apart, leaving the viewer with as many questions as answers by the film’s end.

Such a moment was successfully accomplished for the first time in Burnett’s career with Red Meat, when the motivations and sincerity behind a key character’s backstory is questioned at film’s end.

In the case of Red Meat, The Burnett Epiphany ultimately leaves it up to the viewer to decide how to feel about each of these three men. In doing so, it holds up a disturbing mirror to its audience: how you ultimately respond, perhaps, tells you more about yourself than it does the film.

A Flavorless Release

Red Meat eventually was screened at Slamdance in January of 1996, then, unable to find a theatrical distributor, it was acquired by Sundance Channel, who aired it as their first world premiere in November of 1998. The channel’s creative director at the time, Tom Harbeck, stated to Variety upon news of the acquisition, “Discovering great titles like Red Meat is at the core of Sundance Channel’s mandate.”

Combined with overseas sales, the film more than made its budget back, though Burnett or anyone involved with the film has yet to see a dime of residuals. Red Meat ultimately failed to attract any kind of a significant audience. The timing simply wasn’t right for such a challenging and ambiguous film with such discomforting subject matter to have any sort of resounding impact.

Allison Burnett’s work was complete and unfettered in its presentation with Red Meat. It was the first time the complicated nature of his themes and characters were presented with the uningratiating, unobtrusive, near-Kubrickian distance Burnett had always longed for. While the film was as personally and creatively rewarding for Burnett as it could get, Red Meat did nothing to further his career as a director. It would be seventeen years before he would helm another feature film.

As it stands today, Red Meat is nearly impossible to see, as it is unavailable on Netflix or Amazon streaming, and the few used copies of a (poorly transferred) DVD floating around are usually priced upwards of around $20. With themes that are as relevant today as ever, since John Slattery has gone onto become a household name, and because Charlie Lieberman’s gorgeous photography deserves to be seen in its intended quality, Red Meat is a title that is practically begging for an upgraded specialty label DVD/Blu-Ray release in the near-future.

Kino Lorber, Twilight Time, and Shout Select take note.

Home Again

Instead of wallowing in frustration over his lack of audience with Red Meat, Burnett characteristically threw himself into work once again. In 1997, he rewrote the Max screenplay he had originally written with Charles Mattera. Now titled Home, the script still failed to sell, but again managed to prove as a calling card for future work.

As a direct result of Burnett peddling Home, he was hired to write two screenplays in the fall of 1997. One was a Preston Sturgess update called Remember the Night (which was never produced) and the other was an adaptation of a recent L.A. Times article called Resurrecting the Champ. The latter took a full decade to reach production, and will be discussed in a later section.

Burnett was now financially stable enough to buy a house, where he still lives, in the Westwood area of Los Angeles. His girlfriend at the time, a then-unknown TV actress named Naomi Watts, moved in with him, and the two were subsequently engaged.

As is often the case with any good news in Hollywood, it was shortly followed up with the bad. The engagement was called off and Watts moved out after six weeks. As his future would prove, it wouldn’t be the last time Burnett was left heartbroken by an A-list Hollywood talent.

Our piece on Allison Burnett will continue in Part 4 of 9, which will focus on the debacles behind the production of his next screenplay, Autumn in New York, and the publication of his first novel, Chrisotpher.