Introduction

In Hollywood, success for any screenwriter can be a conflicted accomplishment. On one hand, he or she has obtained something only achieved by a select few. On the other, if that writer had any desire for artistic fulfillment on a movie screen, they are more than likely going to lead a frustrated and alcohol-soaked existence.

Allison Burnett has written independent films, a Roger Corman kickboxing movie, a romantic tearjerker starring Richard Gere, a Lifetime romantic comedy, an entry in the vampire/werewolf-centered Underworld franchise, two serial killer thrillers, a remake of an eighties classic, and several other titles you might recognize but probably haven’t seen.

Like any screenwriter, Burnett has experienced numerous highs and lows over the course of his career. Time and time again, he’s been paid very well to see his work butchered and misinterpreted by egocentric actors and misguided directors. What sets him apart, however, is his desire and motivation to create work that maintains true authorship, which can only be found in the two films he’s written and directed and in his six published novels.

When he’s at his best and most in his element, Burnett creates character dramas whose plots unravel following the consequences of organic human behavior. Though still strictly following (and often cleverly playing with) classical narrative structures, he doesn’t force plot points. His influences are more literary than cinematic (he cites Salinger, Tolstoi, Nathanael West, and John Kennedy Toole as some of his primaries), which gives his scripts a uniquely pleasing literary quality.

Such qualities are hard to execute properly on screen, which is why most of Burnett’s studio films never quite live up to their scripts. Small, subtle moments of characterization and language are a large part of what makes his work stand out. When these qualities are too heavily tampered with, his intentions become skewered, and the entire structure his work adheres to inevitably collapses.

If one takes the time to watch the movies Burnett has directed, read his books, and examine the unmolested drafts of his studio screenplays, the connective threads are evident: a romantic heart, biting wit, and characters filled with inner life, conflict, and history. Burnett has endless love for and fascination with human psychology, which he manages to ground with a healthy amount of cynicism. His work is heightened with optimism and romanticism, but is never without an undercurrent of darkness and blunt human reality.

In examining his career as whole, one can discover in Burnett a hidden auteur who used a successful (though artistically frustrating) career in Hollywood to balance out and finance more personal and daring works that truly matter to him.

Now all he needs is an audience.

Part One: A Man Named Allison

Allison Burnett was born in Ithaca, New York on December 16, 1958. Throughout his childhood, his family moved on a regular basis, living in Brussels; Belgium; Charlottesville, Virginia; Cleveland, Ohio; Naples, Italy; then back to Cleveland. During his middle school years, his family settled in Evanston, Illinois, where he remained until he graduated from college.

His father was a celebrated scientist who published 80 papers on the hydra. Sadly, he was also a severe alcoholic, and died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1979. Allison’s father was also a published poet, whose work was once included in an anthology alongside that of Robert Frost and Sylvia Plath. Allison’s mother is a clinical psychologist from whom he has been estranged for more than thirty years. He also has a brother and a sister, but prefers to keep the details of their lives private.

At the age of twenty, Burnett graduated early from Northwestern University, where he majored in The Oral Interpretation of Literature. This allowed Burnett to study both acting and literature concurrently. Burnett won N.U.’s annual playwriting contest his senior year, then moved to New York City shortly after graduation.

After having a miserable experience starring in a George Bernard Shaw one-act play, he officially turned his back on the “dog’s life” of performing. Writing came more easily to him than acting, so it soon became his primary focus. Soon thereafter, Burnett received a one-year playwriting fellowship to Juilliard. While there, he met an actress, got married “way too young”, and quickly found himself a divorcee at the tender age of 25. He says now of his life at the time:

“Throughout my twenties in Manhattan, I struggled for both creative and financial survival. To pay the bills, I tutored high school kids in the SAT and proofread from midnight to dawn at a midtown law firm. The rest of the time I wrote novels and plays. I had no connections, no agent, no hope of success, but I stayed at it. It wasn’t until I was thirty that I turned to screenwriting and finally found some success.”

The Convict and the Literary Type

Allison Burnett’s screenwriting career started on Jason Bateman’s couch.

To backtrack, while still living in New York, Burnett was introduced to a retired bank robber and ex-convict named Charlie Mattera. The two struck up a friendship and penned two screenplays together on the East Coast, Shooting Large and Inside. Burnett says now of the unlikely pairing:

“I knew that writing with Charlie was going to get me a career, for the simple reason that writing about things outside the ken of my experience would deliver me from the narcissism that plagues so many young writers. In my twenties, writing was too often a form of self-therapy. I knew that writing about criminals and cops would force me to enter the world. And it did.”

Mattera, a charismatic and outgoing Italian-Jew from Coney Island, successfully complemented Burnett’s passive role in the partnership. Networking came naturally to Mattera, proven by an evening in the late-eighties where he struck up a random friendship with Jason Bateman at a Manhattan nightclub.

The young Valerie heartthrob, upon hearing about his screenplays, invited Mattera to move to Los Angeles and crash on his sofa. Mattera accepted the invitation in a matter of days and, through Bateman’s social circle, quickly landed a literary agent named Nancy Gechtman. In September of 1990, Gechtman sold Inside, a prison drama co-written with Burnett, to Roger Corman for a whopping sum (by Corman standards, at least) of $10,000.

This was all the encouragement Burnett needed. Within a week of the sale, Burnett, a self-described “devout lover of terra firma”, boarded an Amtrak to join Mattera in Los Angeles.

Bloodfist 3: Forced To Fight (1992)

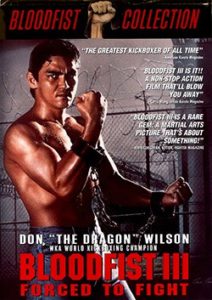

Inside, based on Mattera’s real-life prison experiences, was intended to be a gritty and honest look at gang life behind bars. By the time Corman released the film, it had devolved into a C-level kickboxing movie entitled Bloodfist 3: Forced to Fight.

As such fare goes, it was a success, spawning another five films in the franchise. As a film, it’s terrible but not without its low-budget charms, such as the performance of Richard Roundtree (Shaft) as a jailhouse lawyer. Roundtree’s performance won him a Golden Hubcap Award for Best Actor from cult drive-in movie reviewer Joe Bob Briggs. Burnett and Mattera were nominated for Best Screenplay.

According to Burnett, the experience was a brutal introduction to Hollywood:

“When I learned that Roger Corman had purchased Charlie’s and my screenplay Inside, I was so naive as to be thrilled. I thought, “Good for Roger Corman, wanting to finally make a good movie.” Based on Charlie’s own experiences, it told the story of Jimmy Boland, a white prisoner who kills a black prisoner behind bars. The black prison gang wants him dead for his crime. The white-supremacist biker gang wants him to recruit him as a hero. What neither knows is that Jimmy killed the prisoner in defense of another black prisoner. In other words, our hero’s action was color blind.

A week later, Charlie and I sat in Roger Corman’s office, waiting for the great man to appear. On the wall hung a cheesy poster for Bloodfist 2. I pointed to Don “The Dragon” Wilson and said, “There’s our hero,” and Charlie laughed, of course, because our movie hinged on Jimmy being white. A minute later, Roger walked in, pointed to the poster, and said “There’s your Jimmy Boland.” We were horrified. Roger went on to explain that Don was not a strong actor and so, in our rewrite, we should keep his dialogue to a minimum. We were also told we should cut the cast down by half, as well as cut down by half the number of locations. I wanted to throw up. Welcome to Hollywood.”

Many legendary directors (including Coppola, Scorsese, Demme, James Cameron, Ron Howard, Joe Dante) cut their filmmaking teeth on Roger Corman productions. Most speak of him as a mentor who gave them the opportunity to prove themselves before anyone else would. Burnett, however, doesn’t look back on his brief time in the Corman trenches with the same nostalgic sentiment:

“Six months after the completion of our bad movie, Roger offered us three thousand dollars each to rewrite our script, tailoring it to a female prison in Mexico. We had reached the limit of our capacity for humiliation and told him no. Because he ran a non-union shop, we had no rights, so he merely hired someone else to do it. I heard from a Corman veteran that he remade our identical script two more times. One version was set it in the Philippines, I believe.

I learned nothing from Corman, except why the Writers Guild is so important. I don’t romanticize Roger’s work. While he is a lovely man, with few exceptions (most notably, perhaps, Bogdanovich’s Targets and The Little Shop of Horrors), his legacy is a pile of junk, created by financially exploited artists. The vast majority of his library will sink into the sands of time, as though he had never existed. A shame, because he had the resources, brains, and talent to do much better things.”

Max (Unproduced)

Now Los Angeles residents and professional screenwriters, Burnett and Mattera continued churning out screenplays together. They wrote spec after spec for months, all the while accumulating over $30,000 in debt in Burnett’s name. Their fifth collaboration, Max, finally gave their careers the push it needed.

Finished in the fall of 1991, Max was inspired by a loose idea of Mattera’s about a child entering an empty house haunted by the ghosts of jazz musicians. Burnett took the story in a different direction and hammered out a script in just three weeks. Burnett remarks today, “It was the fastest I had ever written anything. It almost felt like channeling.” The movie was designed to be a thriller for kids, and was now the story of a young boy who came upon the ghosts of a Depression era family in a burnt-out Victorian house. Burnett listed both his and Mattera’s name as the writers, even though he had written the script alone. “I decided it was time to pay Charlie back for all his tenacity and loyalty,” Burnett explains.

The script was extremely well received, landing them a powerful manager in Gary Goldstein, who also represented Pretty Woman screenwriter J.F. Lawton. Burnett and Mattera were sent all over town for roughly 75 meetings. Burnett says of that exciting time, “Everyone wanted to meet the convict and the literary type who had written a kids movie together.”

While the studios deemed Max too dark to be produced, the meetings proved to be a launching pad. Within a couple months, Disney gave them their first writing assignment, which led to their admission into the Writer’s Guild.

Mattera and Burnett would go on to write three screenplays together for various producers on the Disney lot. “The studio was famous in those days for its stinginess”, Burnett says. Their contracts were for union minimum, and those wages were not enough to keep Burnett from having to declare bankruptcy in 1992.

Despite the success of their collaboration, Burnett continued to write his own screenplays at night, after a long day’s work with Mattera. He was determined to create his own professional identity outside the partnership.

Our piece on Allison Burnett will continue in Part 2 of 9, which will focus on his first produced solo screenplay and the next steps of his screenwriting career.