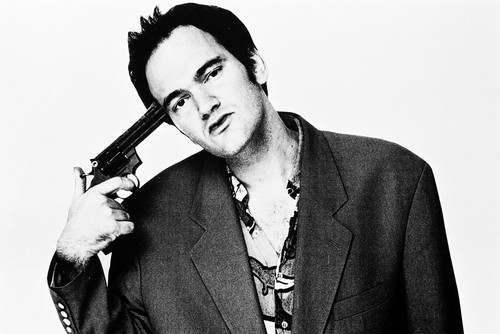

I’ve had a love/hate relationship with Quentin Tarantino for nearly three decades. I can now admit that I never completely forgave him for becoming, well… Quentin fucking Tarantino. I was there at the beginning when he was an up-and-coming screenwriter who’d made his directorial and writing debut with this amazing indie that everyone was talking about back in 1992. He was something completely fresh and exciting, an utterly precious new arrival who made those that were aware of his talent feel special for recognizing it. This was before every film geek and film student considered every word out of Tarantino’s mouth as gospel. This was before he was considered the greatest filmmaker of his generation. This was before the majority of filmgoers even knew his name.

I rented Tarantino’s debut on VHS the first weekend it became available in April of 1993. After the night I watched Reservoir Dogs for the first time, I devoured every interview and piece of information I could find on the man (and this was back in pre-internet days). He was getting mentioned in magazines like Film Threat and Premiere as a name to watch. There was a fantastic interview with him in the Faber & Faber Projections book series where he talked about his goals, influences, and inspirations.

In interviews, Tarantino’s enthusiasm for movies was clear and contagious. He was a high-school dropout who had worked in a video store and learned how to make movies by watching them endlessly. He was a self-described film geek with an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema. He was a film fan with few connections who managed to find success in Hollywood solely through the quality of his work. He was a beacon of hope for all the wannabe filmmakers who had no previous ties to the Hollywood industry. If Quentin Tarantino could make it, then that meant there was a chance that anyone with true talent and passion could make it, too. Simply put, Quentin Tarantino was the me that I wanted to be for as far back as I could remember. My connection to the man and his work was so deep that it forever changed me at my core.

Interviews and articles also revealed that Tarantino was working on his next great movie as a director and that he had written the screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers, which were being directed by Tony Scott and Oliver Stone. He was also reportedly writing a script to be directed by John Woo but, sadly, this one never came to fruition. Romance and Killers, released in September of 1993 and August of 1994, turned out to be just as thrilling and awe-inspiring as Dogs. They were both clearly as much the product of their powerful directors as they were of Tarantino’s sparkling ingenuity. Both films contained what would come to be known as the primary elements of which Tarantino’s unique voice was comprised: endless popular culture references, snappy dialogue, highly witty humor, and sudden bursts of shocking violence.

Then Pulp Fiction, Tarantino’s second directorial effort, was released in October of 1994. After that, everybody knew his name and nothing would ever again be the same. He no longer solely belonged to the fringe movie geeks who had previously fallen in love with him. Quentin Tarantino became an atom bomb whose powerful presence forever changed the way movies were made and seen. It quickly became clear that we needed him long before we knew he existed, and the only person who had the foresight and the courage to fulfill that need was the man himself because he’s Quentin Tarantino… and the rest of us are not.

After Pulp Fiction’s success, Quentin Tarantino quickly became the cinematic equivalent of Kurt Cobain. Nirvana blew bloated, effects-heavy rock albums away in the early 90s just like Tarantino blew bland, effects-heavy, and big-budget studio films away in the mid-90s. Tarantino made loving independent movies, and being a movie geek in general, cool. His first two directorial efforts are ingeniously written, classically staged, expertly shot with long and lingering takes, and feature scenes accompanied by largely forgotten pop music from the 60s and 70s. These elements became part of Tarantino’s highly influential style, an exhilarating blend of both escapist entertainment and high art with independent sensibilities. Every frame of one of his early films is bursting with his own unique point of view. He was an anomaly at the time of his rise, and nothing quite as influential has since happened in the world of cinema. Better, more mature movies have since been made, but nothing has come close to swaying or capturing the world in a similar manner as Tarantino’s early work. Sure, his movies may be hybrids of countless other movies that came before them but, haters be damned, Tarantino is still a hundred percent an original. Not necessarily with ideas but rather in presentation, which, at the end of the day, is what movies are all about.

Other filmmakers of his generation who also exhibited similar and independent-minded sensibilities benefitted from Tarantino’s success. Robert Rodriguez, Tarantino’s spiritual cousin on one side of the coin, came shortly after his rise and created hyper-violent, darkly comedic genre tales that were inspired by John Carpenter and John Woo. Kevin Smith, Tarantino’s spiritual cousin on the other side of the coin, also came shortly after his rise and made dialogue-heavy, character-driven, pop-culture-analyzing indies inspired by Spike Lee and Jim Jarmusch. Tarantino, however, was still in a league entirely of his own and was the central embodiment of it all. While it’s up to debate if he is, in fact, the best filmmaker of his generation, it is indisputably clear that Tarantino has always been the loudest, most noticeable, and most influential.

It is often the case with popular culture that, as soon as something is a success, it is soon copied to death. As special as they initially were, Tarantino’s style and voice were soon spoiled by countless knockoffs. For every new Tarantino film in the 90s (and there weren’t that many), there were at least five other like-minded films that weren’t half as good. Things To Do in Denver When You’re Dead, 2 Days in the Valley, and Truth or Consequences, N.M are just a few examples of movies that aspired to reach Tarantino’s hip cleverness but failed to capture his soul. Pop culture references and overtly witty humor mixed with icily detached violence gave filmmakers an instant cool card. Generations coming up behind Tarantino had no choice but to think that a movie like Boondock Saints was actually good and original (which, by the way, it’s not).

Tarantino himself eventually became a victim of his own success, as well. He appeared to have a blast with his newfound fame, endlessly appearing on talk shows and magazine covers in the months and years after Fiction’s breakout success. His overexposure, which seemed to be evident to just about everyone but him, made his once-charming passion seem like arrogance and vanity. Going one step further, Tarantino also took advantage of his fame to realize his longstanding dream of becoming an actor. He guest-hosted an episode of Saturday Night Live and costarred in the comedy, Destiny Turns on the Radio, in 1995. In 1996, he costarred with George Clooney in the production of one of his earlier screenplays, From Dusk Till Dawn, which was helmed by his frequent colleague and friend, Robert Rodriguez. Though Dawn is a perfectly entertaining horror/action hybrid, it somewhat marked the beginning of the end of Tarantino’s artistic growth (at least for a while). The film is full of Tarantino’s trademarks, but it lacks the emotional grandness that pushed his early work into the realm of greatness.

For the last time in what would later prove to be years, Tarantino attempted artistic maturity with his Fiction directorial follow-up, 1997’s Jackie Brown, an impressively astute and character-driven crime drama based on Elmore Leonard’s novel, Rum Punch. Tarantino’s efforts with Brown simply didn’t produce the same attention as his flashier early films, though it had solid box office returns and was almost unanimously supported by critics. Jackie Brown’s quieter, milder success perhaps made Tarantino think twice about allowing his voice to develop and evolve in a more adult-oriented direction. After the film’s release, he seemed to be more interested in appeasing his (and his audience’s) inner teenager than he was in refining himself as an artist.

For a long time after his rise, Tarantino simply stopped growing. One could even go so far as to argue that he actually reverted backward. He continued to explore the same territory in his films for years, whether they are set in the present day, WWII, or the Old West. Tarantino is safe there, he is loved there, and nobody does it as well as he does it. But he already did it thirty years ago, he built his career on it, and it is no longer as amazing as when he first started it. Tarantino’s style and voice are a nice whiff of nostalgia now, but they’ve also grown to be mildly unsatisfying, especially when considering the other directions and paths of growth he could have taken with his career.

With his later work, Tarantino stopped writing about real people with real emotions and, instead, created movie characters who behaved with movie logic. His early work felt more personal and authentic. At first in his career, Quentin Tarantino wrote and directed movies that he simply had to make because they were so full of life and passion. Everything that came between Brown and Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, however, felt like they were made out of obligation to keep his career going and to please producers and fans.

Tarantino, for me, will always be the guy who wrote True Romance and Natural Born Killers, directed three great movies (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Jackie Brown), then disappeared in the late 90s until he resurfaced in 2019 with the rediscovery of his voice in Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood. There are some highly entertaining movies that came in between but they all had (in varying degrees) a forced, copied, and immature quality that was self-consciously trying to live up to a Tarantino brand rather than the organic spontaneity of his first films.

That being said, Tarantino has never made a bad movie. In fact, he’s never made anything less than a good one. 2003 and 2004’s Kill Bill movies, 2007’s Grindhouse, 2009’s Inglorious Basterds, 2012’s Django Unchained, and 2015’s The Hateful Eight are all wonderfully entertaining and notably inventive films that provide solid escapist entertainment. They contain elements of Tarantino’s early work but they also lack a subtle (though quite noticeable) authenticity. These later films look and feel like Quentin Tarantino movies but they lack the sincerity and passion of his best work. Tarantino’s early success enabled him to make any movie he wanted to make for the rest of his life, but it also took the emotional core from his work that initially made it so spectacular.

Dogs, Romance, Killers, Fiction, and Brown all seem to have come from Tarantino’s desire to communicate honest and true-to-life emotions. Dogs explores a highly moving surrogate father/son relationship between a criminal and an undercover cop. Romance is an idealistic and optimistic movie about young love. Killers, despite Tarantino publicly disliking and disowning the final product, thoughtfully examines America’s relationship with violence and how it is sensationalized in the media. Fiction features a mix of characters living lives of crime while simultaneously longing for something greater and more fulfilling. Brown is a tragic and moving romance between two people who, despite a deep mutual attraction, could never realistically end up together. All of these films are entertaining genre efforts but they are ones that exhibit and examine the human condition in a grounded, realistic, and relatable manner.

Bill, Grindhouse, Basterds, Django, and Eight are all movies that are unabashedly and single-mindedly soaked in movie logic. They are all a significant step down in maturity from Tarantino’s early work, as if they were created by a young artist with a lot of skill but who is still struggling to find something to say. His characters became too cool for reality and too contrived to beget any tangible empathy. They’re movie characters who live in movie worlds. The Bill movies are a simple revenge story featuring a protagonist who unrealistically survives so many countless harrowing ordeals that nothing ever feels like a viable threat. Death Proof, Tarantino’s Grindhouse installment, aims for b-level thrills through characters that talk a lot but actually have very little to say. Basterds is an exploitation war movie with heroically macho good guys versus black-and-white villains. Django turns the harrowing realities of slavery into a comic book-minded fantasy in which good triumphs over evil. Eight is a Western filled with grizzled characters that feel like they were taken from other movies rather than true-life experiences. All the Tarantino movies that came after Jackie Brown are pulpily fun and exquisitely crafted, no doubt, but they also lack the tangible, human relatability that initially made his work so monumentally special.

Then, in 2019, Tarantino redeemed himself with the release of Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood. Though it is filled to the brim with many of the trademarks that made him a household name, it also contains the most emotionally honest characters he’s had in any of his movies since Brown. Rick Dalton, the main character of the film portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio, may be a fictional movie star but he’s also one of the most messily human characters that Tarantino has ever created. Dalton is an insecure alcoholic suffering from bipolar disorder (as revealed by Tarantino in his self-penned Hollywood novelization). We see Dalton display Tarantino’s signature movie coolness while he’s performing but, as soon as the cameras aren’t rolling, he becomes achingly and unpredictably real. Dalton, along with other characters in the film, seems to come purely from Tarantino’s heart instead of a forced desire to live up to his “Cinema of Cool” reputation.

Quentin Tarantino has, to date, directed nine movies (if you count the two Kill Bill movies as one). He has publicly stated for years that he intends to stop making features after his tenth one so he can focus on other mediums. Whatever his final film may be, he already reached an appropriate climax to his career with Hollywood. It feels like it should be Tarantino’s last movie because it serves as a perfect summation of the best of what he has accomplished in his career. It mixes the sincerity and personal nature of his early works with the technical skills and highly identifiable style that he honed with his later works. It is truly the best of both worlds, and the film will, hopefully, be increasingly considered as one of his best in the years to come.

Tarantino’s effect on and place within the film industry is hard to summarize with brevity and simplicity. He holds more power and influence than just about any other director living today. He has proven repeatedly that his image can survive just about anything, including an arrest for assault on one of Natural Born Killers’ producers, Don Murphy, thoughtless public comments about Roman Polanski’s sexual assault victim, and his decades-long relationship with notorious Hollywood producer and predator, Harvey Weinstein.

We are currently living in a world where people’s careers are being destroyed for things they’re saying and doing both in and out of the workplace. Tarantino, however, remains untouchable. In early 2018, a New York Times article was released in which Uma Thurman claimed that Tarantino bullied her into performing a stunt for Kill Bill that frightened her. The stunt backfired and has caused her chronic pain ever since. If true, this incident was on-set, at work, and life-threatening. Shortly before this, Tarantino also publicly admitted to knowing about some of Weinstein’s serial sexual abuse while it was still happening, yet he still continued to work with him until everything became public. Despite all this, everyone in Hollywood is still lined up to do Tarantino’s next movie without an afterthought. James Gunn, on the other hand, made offensive/sarcastic jokes on Twitter and was consequentially fired from directing the third Guardians of the Galaxy movie over eight years later. Though Gunn was eventually rehired, the damage was done and the message was clear: it’s okay to be an abusive, irresponsible asshole in Hollywood as long as you’ve made classic movies and everyone thinks you’re a genius.

Whatever quality of person he may be in his private life, Tarantino’s influence on modern filmmaking is impossible to deny. Today’s film industry truly would not have been the same without him. This is a good thing to many and something to be concerned about for many others. However you feel about his work then or now, there is no denying that Tarantino paved the way for the next wave of great and risk-taking filmmakers (Fincher, Nolan, Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson). Their challenging and unique movies may not have existed in an industry that wasn’t so heavily influenced by Tarantino. Though many of these films have received praise, had massive success, and caused cultural splashes since Tarantino’s rise, nothing has scorched the Earth in the same manner as his early works. Everything, including the celebration of individual filmmakers, peaked with him. Like the shadow of Orson Welles hanging over the Scorseses and the Coppolas of their generation, it is Tarantino’s world today and everyone else is merely a visitor.

When the scores are tallied, Tarantino hurt the film industry as much as he helped it. Sincerity and serious drama have become increasingly scarce in popular films since his rise. Movies with bold messages that cater to adult thinking became targets for cynicism, something critics disappointingly jumped on as much as hipster audiences. Directors like Oliver Stone and Spike Lee, both of whom were idolized in the press in the years prior to Tarantino’s rise, came to be viewed as heavy-handed and overbearing filmmakers who deserved to be shamed for trying to say anything important, political, or revealing in their work. Film became a bad word when Tarantino took over the filmmaking White House, and movies that proudly had nothing to say about the human condition became commonplace. Much like Lucas and Spielberg in the generation before him, Tarantino’s escapist pieces of entertainment—despite their artistic sensibilities—gave audiences what they wanted so plentifully that it made them forget about the power of movies that aimed to be intellectually stimulating and/or emotionally fulfilling.

None of this was directly Tarantino’s fault, however. Like the studios and conglomerates crunching numbers to give the people what they want, Tarantino doesn’t give the world anything it isn’t demanding. Though massive success undeniably influenced his career’s direction, it’s still hard to think of him as a complete sell-out because he’s always been doing his own individualistic thing. His thing just happens to be a massive hit with popular culture, and he has continued to put it out there for a very welcoming audience throughout the years. Most of his followers and fans seem to have adopted his influential logic along the way: movies are movies, rides made to entertain and provide an escape. If you have something to say, say it elsewhere, and use another medium. And if you aren’t cool enough to get that, just fuck off and watch Howard’s End, alright?

You’ve gotta love Quentin Tarantino every bit as much as you hate him. By the time we entered the twenty-first century, filmmaking as we knew it had already ended with him. Where the medium goes from here and whether it continues to thrive is really anyone’s guess. Will the next great, globally celebrated filmmaker make features, or will he or she work in another format like web videos or ongoing streaming series? Will we continue to dwell on surface-driven escapist yarns, or will we, once again, search for something grander and more meaningful? Time will tell, but it’s inevitable that someone will eventually come along to scorch the cinematic earth that has displayed Tarantino’s signature since the early 90s. Nothing has made the kind of impact he made since, and many of us are hungry for a long-overdue something that is equally astonishing and new. Simply put, we’re all ready and waiting for the next Quentin Tarantino to come and shake things up all over again.