Movies aren’t important anymore. What were once magical, intangible showcases of our collective dreams have since become modern-day elevator music. People are watching movies today more than ever, but they’re not truly paying attention to them so much as they are just… letting them merely exist and wash over them. People just aren’t as enamored by movies as they used to be. Thanks to the Netflix day and age, movies are now cheap. They are wallpaper. They are something to have on in the background, but are rarely something that is worthy of our full attention.

The movie industry has changed and is still changing every day. Too many movies are being made today. There’s more product than there are consumers demanding it. The great movies, which are still being produced, simply aren’t being discovered. On the rare occasion that they are recognized, they’re soon forgotten about, as individual titles no longer have the staying power they need or deserve. Simply put, the movies are still here for us, but we’re no longer there for them.

There’s so much available content that it has become a rarity for anyone to take the time to properly examine and peel the layers of just one particular movie. How can we? As soon as a great movie is released, a newer, shinier one comes along shortly after and draws all our attention to it. As a result, many movies are becoming even more surface-driven. They need to get in, get out, make their point, and entertain us with the first try. Forget having a conversation to put its pieces together or seeing it more than once to make complete sense of the filmmaker’s intention. Movies may last forever (or as long as our technology can sustain them), but that doesn’t mean they don’t have an expiration date.

Movies basically started as a magic sideshow experiment in 1895 (Look at that light hitting the screen! Look at those pictures move!) when the Lumière brothers first presented the moving image to audiences in Paris, France. No one quite knew what to make of the technology, then. When it was introduced to the general population, it had the same novelty as a static machine that makes your hair stand up on end does today. Motion pictures were something otherworldly achieved through the wonders of science. Little did anyone know that the moving image would go on to replace the written word as our primary source of communication and entertainment well before the end of the 1900s.

After film’s invention, filmmakers quickly began to treat it as a storytelling device and an art form. Given the inherent spectacle of their nature, movies quickly became the most powerful way that human beings could relate to the stories and experiences of others. Roger Ebert once called movies a “machine that generates empathy”, and he couldn’t have been more accurate. Movies don’t just show you other people’s lives, they have the power to let you live them for the briefest amount of time.

D.W. Griffith, George Melies, and Sergei Eisenstein, to name a few, were some of film’s earliest creative visionaries. They made films that pushed the medium’s boundaries through technique, technological development, and narrative structure. Orson Welles then, somehow, brought every major development together in the early 1940s with his celebrated masterwork, Citizen Kane. The film is, arguably, the seed from which modern-day cinema grew. Welles never got the credit or respect he deserved for Kane’s influence until much later, but his imprint on the evolution of filmmaking is undeniable and irreplaceable.

Still relatively new to having the medium be a part of their everyday lives, people romanticized movies far too much during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Movies were seen as pure magic at this time, and they could easily make anyone who created or appeared in them seem more than human. Movie stars were godlike celebrities. The faces that were projected twenty feet high were no longer human. They were, quite literally, above us. This viewpoint continued well into the 50s with the idolization of such massive stars as Brando, Monroe, and Dean. Movies, and the stars that inhabited them, were greater than us and far more beautiful than anything we could imagine on Earth.

This mentality has yet come to a complete end (look at the fascination and contempt we have for today’s cinema celebrities), but it was strongly rivaled in the 40s and 50s when the “auteur theory” was developed by André Bazin, Alexandre Astruc, Andrew Sarris, and, ultimately, Francois Truffaut. This theory started in France, and it explored the idea that a film’s director was the primary creative force behind it. Everyone else—actors, cinematographers, designers, etc.—was only working to fulfill the director’s singular vision.

With such new movements taking place, some filmmakers began to ignore the glamour of moviemaking and instead brought grit, reality, and their own unique perspectives onto the big screen. An increasing number of American filmmakers took France’s cue and made films that were more concerned with art than commerce. In many circles, the Golden Age was long gone. Those movies were fantasies made for children. It was time to put real life, real experiences, real violence, and real sex onscreen.

Then came the 60s and the early 70s. During this time, directors and the art of cinema were held in the highest esteem. Movies were then–in the eyes of filmmakers, critics, and sophisticated audiences–sacred. Movies could transform, transcend, and awaken something inside each viewer. Polanski, Hopper, Kubrick, Peckinpah, Penn, Nichols, Scorsese, De Palma, Coppola, Bogdonavich, Altman, and many others created films that were the most modern and advanced forms of artistic expression. These directors were creators, painters, and authors. Film was a personal, singular point of view and the director was God. In a matter of just a few years, however, movies would become a marketing tool to help sell toys at McDonald’s.

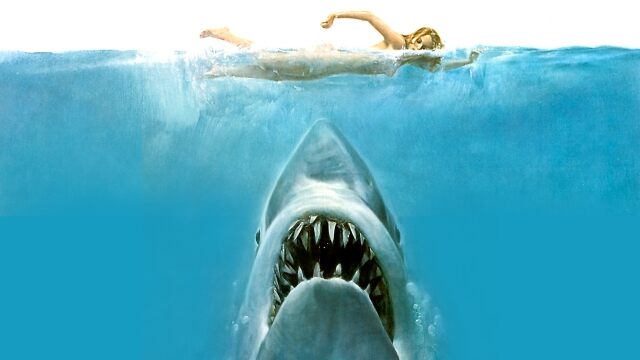

When Spielberg and Lucas hit it big in the late 70s with their big-budget crowd-pleasers, Jaws and Star Wars, everything changed. Popcorn movies subsequently took over the box office. Movies, by and large, quickly became the most popular form of escapist entertainment. Anyone trying to create art through cinema would have to face an uphill battle from then on.

The theatrical experience, which was then the most popular and enveloping way to view movies, was heavily threatened in the 80s and 90s when home video cassettes (VCR, Betamax) and, to a lesser degree, early video discs (DiscoVision, LaserDisc) became popular. While the accessibility of movies increased and made them even more in demand, the theatrical experience was being more and more replaced by the convenience and comfort of viewing them at home. Cable television also became increasingly prominent during this time and was another great threat to theaters. The social experience of going to a movie theater and seeing movies on the large screen with a large crowd was similar to a religious experience for the most passionate of filmgoers and filmmakers. The act of viewing movies at home, despite its many positives, cheapened them in the long run.

In the 80s and 90s, movies were about as popular as you could get in popular culture. Corporations took over studios and created an overload of increasingly formulaic films that found their way into theatres and/or on home video and/or on cable television on a weekly basis. The studios made what the people wanted because the people gave what the studios wanted: money. Studio heads, producers, and accountants were the new auteurs behind the majority of films being made and distributed in the United States. And the choices they made were not based on creative passions, but rather on numbers and the opinions of businessmen as to what might sell.

Not to say there still wasn’t great work being done during that time. There were still a number of worthy successors to the auteurs of the previous decades who were set on making unique, artful, and/or provocative films for adults. Spike Lee, Terry Gilliam, The Coen Brothers, David Lynch, and Oliver Stone, to name a few, were some of the greats who managed to create work that reached and challenged mainstream audiences. Scorsese, Altman, Kubrick, and De Palma also managed to continue to create great, personal works. Some of these filmmakers, well into their fifties, sixties, or seventies, were actually just starting to enjoy the peaks of their critical and financial successes (you could argue Scorsese’s career didn’t come full circle until the 2000s). The time was a strange transition that showcased the best and worst of what movies had to offer.

In the late 80s and into the 90s, independent filmmaking started to make its way into the mainstream. Lee, the Coens, and, eventually, Steven Soderbergh started their careers with independently financed productions. Other filmmakers followed, giving way to a plethora of fresh, thoughtful, and artistically minded films. The movement culminated in the early 90s with the arrival of someone who would find both extreme critical appreciation and massive mainstream success. His name, of course, was Quentin Tarantino.

Tarantino couldn’t have come at a better time. The 90s were a cynical time in which it was hard to impress everyone. The movie-going public, in general, was tired of romanticized matinee idols and was even more exhausted by the increasingly soulless and formulaic movies being produced by major studios. Tarantino, and the movement that came with him, broke all the rules that Hollywood seemed to have set for itself.

Tarantino was a much-needed breath of fresh air for critics and audiences looking for something new. Hollywood norms, such as the yearly Academy Awards, that were once treated with near-religious importance were starting to be viewed as narcissism-fueled bonfires of the vanities. Audiences still loved movies, but they were tired of getting their noses rubbed in how wonderful they were.

The mystery of the movies and their magical intangibility were fading in the 90s. Their many secrets were being revealed in supplemental home video features or on entertainment talk shows. Everyone knew how they created the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. Everyone saw how they did the opening shots for Cliffhanger. People were being wowed less and less, and they were hungry for something different and new, and something that reflected the skepticism everyone was feeling at that time (it’s what the 90s were about, man…). The public still loved their Hollywood icons, they still put them up on pedestals, and they still tore them down when they were ready for someone new. Audiences were simultaneously starting to see through the Hollywood façade, however, and they were getting tired of it.

For the briefest period of time, independent film was king and Quentin Tarantino was its God. Quirky sensibilities, good writing, and relatable themes were, in certain circles, being favored over trite, high concept films that neatly fit into a specific genre. A new breed of filmmaker, audience, and genre was born. Movies could now be something completely different from what the public previously knew them as.

As is the problem with every new and exciting artistic movement, it quickly became not so new and not so exciting when everyone started to copy it. “Independent” simply became a new label and its own genre. Within just a few years of the creativity that exploded because of Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez, Kevin Smith, and others came the inevitable backlash. What was new and different in ’94 became just another part of the Hollywood conveyor belt by ’97. In order to be considered hip, different, and cool, movies had to subscribe to certain aesthetics and rules to be considered as such, and, once they got into that club, they were really anything but.

That being said, there were just as many positives as there were drawbacks to the 90s independent revolution. Studios took more chances on interesting filmmakers, which paved the way for the next wave of them in the late 90s and into the 2000s. Without Tarantino and the rise of the independents, we very possibly wouldn’t have the best works of such great filmmakers as David Fincher, Paul Thomas Anderson, David O. Russell, Danny Boyle, and many others.

For a while, into the late 2000s, the movie business hit a plateau. DVDs and other home video formats peacefully coexisted with the theatrical market. Blockbuster or Hollywood Video stores were present just about everywhere, as were AMC or Cinemark theaters. Multiple cable television outlets, such as HBO or Showtime, were also able to thrive along with the other major release platforms. Then, everything was thrown into upheaval and would never again be the same when the digital age began and took hold of the entire industry.

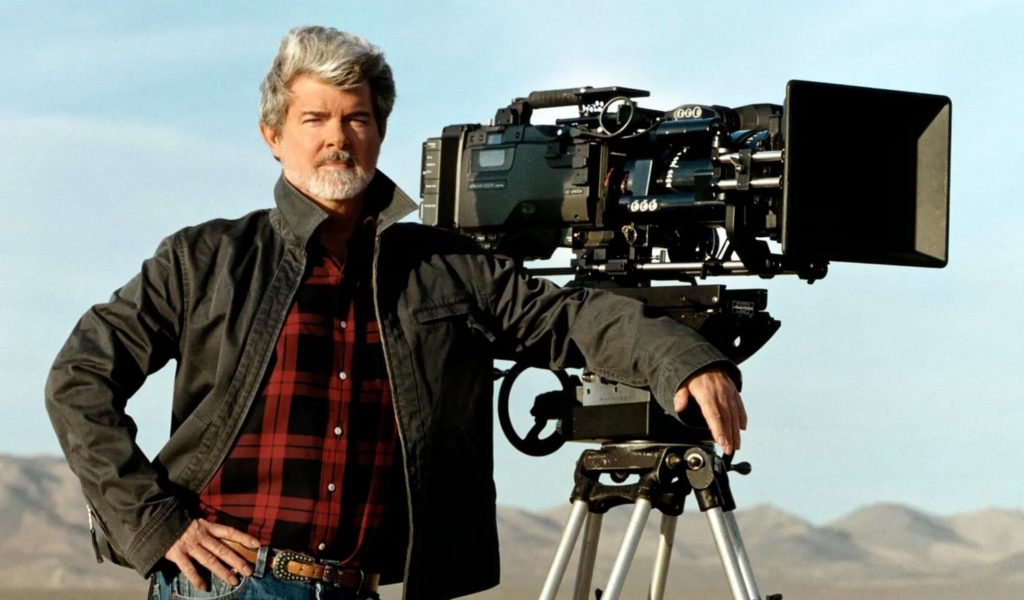

The first thing the digital revolution sent into upheaval was how the movies themselves were made. Though some loyalists (Scorsese, Tarantino, Spielberg) primarily stuck with celluloid, digital cameras and post-production computer programs provided quicker, easier, and cheaper results with comparable quality. George Lucas, having already revolutionized visual effects and filmmaking with Star Wars in the 70s, did it again when he released the first film to be shot completely digitally in 2002 with Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones. Many filmmakers, excited by the possibilities of the new technology, quickly followed in his footsteps.

It still remains to be seen whether the digital revolution is a new beginning for or the beginning of the end of the film industry. Filmmakers no longer had to carefully work with celluloid film strips or precise chemical processing. They now worked with digital files and, essentially, thin air. The physical presence of films and their tools of creation became intangible. Many filmmakers didn’t see the difference and embraced the technology for what it was: an easier and more efficient way to make films.

What difference does it really make whether it’s pixels or celluloid as long as good stories are being told with care and craftsmanship? That’s the thing, however. The same care and craftsmanship–in cinematography, editing, direction, performances, writing—is now largely gone. You don’t have to be as careful in the digital age. Filmmakers, in general, are now too reliant on “fixing it” in post-production. Digital filmmaking allows for more films to be made at a faster rate, but it does so at the cost of their integrity and soul.

It was only a matter of time before digital technology overtook how movies were viewed. In the early 2010s, digital projectors replaced celluloid at just about every theater in the country. Streaming platforms such as Netflix had already been taking over countless households, allowing for audiences to watch a variety of movies at home with the few simple clicks of some buttons. No more paying for late fees, no more traveling to the theater or rental store, and no more dealing with crowds or sold-out shows. Theaters and, especially, video stores (which are currently all but obsolete) suffered as a result. Movies became less of a social or soulful experience, and more of a lonely one that merely passed time until something better came along.

With all the new technology and all the available release platforms, more and more movies are being made today. So many, in fact, that it is easy for even the most high-quality of them to get lost in the shuffle. Many great films aren’t being recognized today because there’s too much competition from newer, louder, faster films. And, sadly, audiences, in general, have seemed to stop caring about films that hold cultural or artistic importance. Great films by Nicolas Winding Refn, Harmony Korine, David Gordon Green, Derek Cianfrance, and Greta Gerwig are managing to find audiences, but they still don’t hold the same importance that they would have twenty years earlier.

Aside from the saturation of titles being produced, movies also have to fight their audience’s lack of focus today. Youtube, video games, and Facebook (just to name a few) robbed people of their attention spans, and made it next to impossible for them to focus on something for two whole hours! There’s too much information all the time. There’s too much out there to care about any one thing, let alone one movie. Movies aren’t important anymore because nothing seems to be important, anymore.

At the end of Hearts of Darkness, Francis Ford Coppola hopes/predicts that the professionalism of filmmaking will come to an end and that the next big thing will come from somewhere and someone completely unexpected. With all the accessible filmmaking technology available today, this prediction is becoming likelier and likelier. Anyone can make a movie now, but can anyone get it seen by the audience it deserves? If the next great thing in filmmaking appears from some unknown corner of the world, will anyone take the time to notice? Therein lies the real problem facing movies today. Technology has caught up to our imaginations, but, now that it’s available to everyone, it doesn’t hold the same specialness or importance it once did.

Movies are now in a transition period. The spectacles are getting bigger, and they are primarily all you can find in movie theaters. Spielberg and Lucas once predicted that movie theaters will go the way of Broadway shows, and they are being proven more and more correct with every passing day. In the future, seeing a movie in a theater will be pricey, it will be an event, and it will be an extreme luxury. Going to movie theaters won’t be a common part of popular culture, anymore. Theaters will still exist, but only for elite circles. Spectacle will continue to rule as filmmakers and studios will be forced to do some major tap dancing to draw people into theaters.

VOD and online streaming are the new art house, the new home for independent films. Such platforms allow for smaller films to continue being made, but they will also be the reason that most of them will be buried and disappear from public consciousness without a trace. These platforms allow for a plethora of content, but that content will be saturated to the point that no one will be able to decipher what is worth seeing and what isn’t. Smaller, riskier films will still exist, but they’ll have some heavy competition and they most likely will disappear before finding their deserved audience. There will be exceptions, but, as time progresses, they will be fewer and farther between.

So, what’s the answer? Do we give up on movies and move on to the next popular medium (which is most likely going to be something VR-related)? Or do we keep fighting for this art form, which is still relatively new but, very possibly, dying (or, at the very least, heavily mutating)? There just isn’t an easy or obvious answer at this time.

If history has proven anything, it’s that everything is cyclical. The spectacle and glamour of 50s and 60s Hollywood resurfaced with 80s studio blockbusters, just like the wave of auteurist directors in the 70s is similar to the rise of the major independent filmmakers of the 90s. Things have changed before, they will again, and then they’ll go back to a similar, though not necessarily identical, way that they once were. Today, we’re at a strange amalgamation of just about every cinematic movement that has taken place up to now, and it might stay that way for quite some time.

It probably won’t be a theatrically released feature film that reinvigorates and transforms the universe of moving images. It is more likely going to be a streaming series, a feature-length VOD release, or, quite possibly, a short-form Youtube video. Movies today, as we know them, are changing, just like they have been since their invention. What they will ultimately change into and when is really anyone’s guess. It could be next week or it could be another twenty years, but something will happen… and it could be an inspirational new beginning or a more definite ending. Time, as it always does, will tell.

Movies, by and large, aren’t important anymore. There are still plenty of silly and mindlessly entertaining ones that continue to put money in their studios’ pockets, but they are quickly discarded shortly after their release. There are also plenty of films that challenge and surprise us, but the majority of them are hidden in the darkest corners of the internet. Movies may never again hold the same cultural importance they once did, but it is very likely that they will flourish again in some form once the rest of the world is ready to be taken over by something new and special. Film lovers are at a point where they truly need it, and they’re all waiting for the next great thing to show itself and make movies important again anytime now…