Terry Gilliam has lost years of his life and large portions of his already questionable sanity to bring The Man Who Killed Don Quixote to the screen.

The 2002 documentary Lost in La Mancha detailed his first attempt at producing the film in 2000 before it fell apart for one excruciating reason after another. The nearly two decades since–the ones we haven’t seen documented on video (yet)– were just as troublesome: Gilliam had to fight and wait for years to regain the legal rights to his and Tony Grisoni’s screenplay, he repeatedly secured and lost financing, actor John Hurt passed away shortly before he was supposed to begin filming the lead role and, to top it all off, Gilliam again lost the rights to the film after it was already made–which caused him to lose both his U.S distribution and a future production deal at Amazon.

The film was released for a single day in U.S. theaters on April 10, 2019, and is now (very quietly) available on DVD, Blu-Ray, and multiple VOD providers.

The bright side to it all, of course, is that after all those years of suffering, Gilliam finally has a film to show for it. But the big question is, was it worth it? For Gilliam, undoubtedly, as the film–with its in-your-face presentation of chaotic comedy, its whimsically warped brand of fantasy and its themes of contagious insanity–could belong to no one else. For better or for worse, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is quite obviously the movie that Terry Gilliam wanted to make.

But for everyone else…?

Fans of Gilliam’s—the ones who will view the film as a completion of what was started in Lost in La Mancha—will no doubt be thrilled, and they don’t even have to see the movie to feel that way. Just the fact that it exists already makes it a lovable cinematic underdog that refused to give up in spite of having every reason to.

While it’s a worthwhile Gilliam entry, Don Quixote doesn’t quite rank with the greatest of his work, either. Fans seeking a masterpiece companion to Brazil or 12 Monkeys or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas are most likely setting themselves up for disappointment. If fans are willing to accept the compromised version of Gilliam–the one who has had to settle on lower budgets and adjust to the digital world in spite of possessing completely opposite aesthetics–then they might find Don Quixote to be one of his better recent efforts, ranking high amongst the likes of The Brothers Grimm, Tideland, The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus, and The Zero Theorem.

Audiences going in with no previous knowledge of Gilliam or his films will most likely suffer from scalp bleeding after all the head scratching they do while viewing it, however. Familiarity with his work and his struggles in making the film enrich it to an almost necessary degree, which is as much a fault of Don Quixote as it is a strength in Gilliam’s auteurist approach to filmmaking.

When Gilliam tried to make the version of the film that was documented in Lost in La Mancha, it was to star Johnny Depp as an advertising executive who time travelled back to the land and era of Don Quixote, then found himself swept up in the adventurer’s exotic mindset. Gilliam and Grisoni rewrote that version of the screenplay, and the finished film now heavily reflects Gilliam’s ongoing struggles and obsession to bring Don Quixote to the screen.

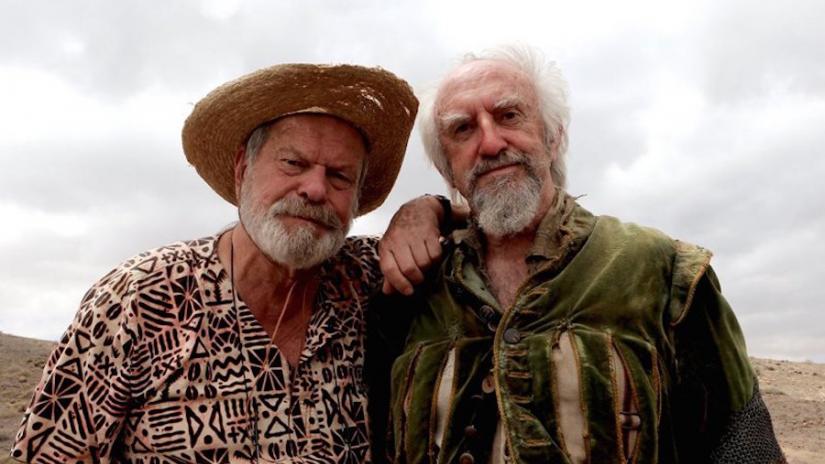

The finished film now has Adam Driver portraying a filmmaker on location in Spain for his latest production. When he comes across a bootleg copy of an early film he made in a nearby small village many years ago, he is reminded of previous passions, obsessions and promises. Upon visiting the village, he discovers that the star of his early film, a local shoemaker (Jonathan Pryce), has fallen under the delusion that he is still the lead character from that film: Don Quixote. And, to top it off, he believes that Driver is his long-lost and forever loyal sidekick, Sancho Panza.

When Driver finds himself in a hairy legal situation involving his powerful producer (a wonderfully imposing Stellan Skarsgard), he is forced to go on the run with “Don Quixote” for a series of surreal and comical misadventures. The deeper Driver’s character goes, the more Don Quixote clearly becomes a Gilliam film as Driver begins to experience and embody Gilliam’s most personal theme of all: the inability to distinguish fantasy from reality.

Where the film truly succeeds is in its early exploration of Driver’s character and his relationship with Pryce/Don Quixote. The early scenes are some of the film’s strongest, featuring a prickly and soul-sick Driver desperately seeking passion and inspiration. Show business has sucked the life out of him, and he is a comically rundown victim of his own success and narcissism.

Driver brings a dedicated and intense hostility to his performance, wound in such a tight ball of disdain that he comes across like a satirical caricature of spoiled Hollywood talent. Gilliam has a great amount of fun exploring the pressure Driver’s character is under, seeming to take an almost sadistic (or, perhaps, masochistic if viewed from the correct angle) delight in lingering and watching him squirm under Skarsgard’s scornful and skeptical gaze.

Driver’s passionate bitchiness is a wonderful complement to Pryce, who tackles the role of Quixote with the appropriately dazed and fully committed theatrics of a madman who thinks himself a hero. The chemistry between the two actors is an extreme highlight of the film. A scene in which they take refuge in a cave provides the audience with the simple pleasure of watching them bounce off each other with a specifically glorious and reckless abandon that Gilliam has always had a knack for inspiring in his performers.

The film falters increasingly as the stakes rise and Driver’s character falls deeper into Quixotic madness, however. The more bombastic and ambitious Don Quixote becomes, the less involving it continues to be. Gilliam’s comically surreal, fantasy-driven tangents are enjoyable and inventive in their own right, but they also interrupt the flow of the film and seem to work against its best qualities.

The building relationship between Driver and Pryce abruptly plateaus before the film’s last act and never builds to the heights the film needs for a truly fulfilling peak or conclusion. The script’s overall haphazard structure successfully reflects the mindsets of its characters, but it’s also exhausting and heavily dulls the film’s potential emotional impact.

One of the film’s weakest subplots involves the rediscovery of a teenage girl (Joana Ribeiro) who Driver cast in his previous movie. In present day, Ribeiro is a broken woman, shattered and scarred by the promises and dreams of stardom that a young Driver put into her head many years prior.

While there is fantastic potential to this narrative, it falls short when it presents itself in the midst of the madness that is already taking over the movie at that point. Driver and Ribeiro both deliver individually strong and committed performances, but their potential chemistry is never fully realized and remains lost in the surrounding noise.

The arc of Driver’s character ultimately underwhelms, as neither Gilliam nor Driver are ever able to fully communicate or provide depth towards how he is affected by his relationships in the film. His character never comes to life with humanity, but I’m not entirely sure he was ever supposed to—perhaps he’s simply meant to embody Gilliam’s increasing cynicism towards the film industry and his inability to walk away from it. Perhaps he wasn’t meant to learn anything from his ordeal and go insane because of it.

While this is a fascinatingly bleak conclusion to come to in the later stages of Terry Gilliam’s filmmaking career, it’s not developed or satisfying enough in Don Quixote to make the film truly great on its own. If Gilliam had found a way to focus more on the relationships in his film (like he did in The Fisher King) and less on frenzied dream sequences he didn’t have the budget to fully support, Don Quixote just might have ranked amongst the highest of his classic works.

After all is said, however, I still can’t help but have a great deal of affection for this movie—not necessarily for what it is on its own, but more for where it fits into Terry Gilliam’s wholeheartedly individualistic career. In spite of its rough edges, Don Quixote still showcases its own Gilliamesque charm—and a mess created by Gilliam is always a very special mess. No matter how disjointed the film gets, you never entirely lose the feeling that you’re in the hands of a master of his own personal genre… You just have to forgive the fact that he may not have the best tools at his disposal, anymore.

Gilliam is one of the last remaining auteurs. Some films, especially those later in the careers of the truest auteurs, simply need some pre-existing knowledge to be fully understood and appreciated. After some filmmakers spend a large portion of their careers developing their own cinematic vocabulary, they (knowingly or unknowingly) can often develop their own shorthand to avoid repeating themselves—which can easily alienate new audiences. Though he’s always been hit-or-miss with the mainstream, Gilliam’s work particularly suffers today because it has to exist during a time that no longer respects or has the attention span for this approach.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, as it turns out, needed its twenty years of baggage in order for its quality to fully stand out. However flawed it may be, that quality–like everything else about Terry Gilliam’s career–is still unlike anything else.

GRADE: B